HAVE YOUR EPIDEICTIC RHETORIC, AND EAT IT, TOO

Rachael Graham Lussos, George Mason University

This article examines how an “occasional cake”—a cake decorated to celebrate a birthday or other event—is an example of epideictic rhetoric and a potential medium for activism. I support this claim with observations from a personal case study, decorating birthday cakes for a charitable nonprofit that provides personalized birthday parties for children experiencing homelessness. In this process, I discovered that the multimodality of the cakes was a significant factor in making a compelling claim that these children’s lives are worth acknowledging and celebrating. I suggest that the making of activist, epideictic, occasional cakes is a potential multimodal composition assignment that would invite students to consider mode and process, cultural values, and relational ethics. In addition to its pedagogical implications, this study demonstrates the importance of investigating the potential of non-digital mediums for making activist arguments.

Introduction

When you make someone a birthday cake, you tell this person that she is valued and her life is worth celebrating. I learned this from my mother, who insists that every birthday be celebrated and every birthday celebration involve a cake bearing the celebratee’s name and an appropriate number of lit candles, which the celebratee blows out while loved ones sing off-key. Wishing is optional.

I started learning how to bake and decorate cakes when I was a teenager, and I have decorated “occasional cakes”—cakes decorated to celebrate birthdays and other events—for family and friends ever since. Although I have always appreciated the role of occasional cakes in various celebrations, it was not until after a decade of baking and decorating occasional cakes that I learned how cakes can function as a type of communicative discourse: epideictic rhetoric.

In On Rhetoric, Aristotle differentiates between epideictic rhetoric and the two other branches of rhetoric—judicial and deliberative—by the time they reference (trans. 2007, 1358b).[1] Judicial rhetoric refers to past events, for which it solicits judgments; deliberative rhetoric refers to future events and proposes actions to either help the events occur or prevent them; and epideictic rhetoric refers to current events and seeks agreement about their honorable or dishonorable nature. Epideictic rhetoric characterizes genres such as eulogies, letters of recommendation, and the Best Man’s speech at a wedding, all of which use a particular current event to praise or blame one’s values.

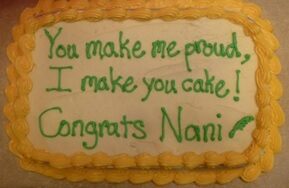

Although common in American and other national popular cultures, occasional cakes are not frequently identified among the common examples of epideictic rhetoric, and yet, this type of cake achieves the same rhetorical function as a congratulatory speech. For example, Figure 1 depicts a cake that celebrates my sister’s high school graduation. The text alone demonstrates praise, and the colors of the frosting match those of her destination university, further highlighting her achievements. Like a commencement speech might, the cake “praises” her for her past accomplishments and looks with hope upon her future.

Figure 1: My sister’s graduation cake uses a pun to demonstrate the relationship between epideictic rhetoric and cake. (Source: personal collection.)

Just as occasional cakes might be dismissed as potential mediums for rhetorical arguments, the significance and usefulness of epideictic rhetoric is also debated. Of Aristotle’s three branches of rhetoric—deliberative, judicial, and epideictic—epideictic is the most likely to be dismissed as “mere” rhetoric: “artificial,’ ‘contrived,’ and ‘irrelevant’…‘empty rhetoric’” (Sheard, p. 766). However, several researchers have argued against this dismissal, claiming that inherent in epideictic rhetoric is the potential for civic contribution or activism (Sheard, 1996; Agnew, 2008; Richards, 2009; Bostdorff and Ferris, 2014).

In this article, I seek to extend previous claims about the civic potential of epideictic rhetoric: I argue that the activist component of epideictic rhetoric is more compelling in a multimodal composition than in epideictic arguments that comprise one mode, particularly when representing the values of marginalized groups. That is, because the voices of marginalized groups are often silenced or ignored, any representation of their values is best communicated through a rhetorical use of material and spatial elements as well as textual. To support this claim, I demonstrate how occasional cakes qualify as an example of epideictic rhetoric. Then I describe a personal case study in which I decorated birthday cakes for a charitable nonprofit called Extra-Ordinary Birthdays, which provides personalized birthday parties for children experiencing homelessness. Finally, I address the pedagogical implications of this study, suggesting a multimodal project to help composition students consider processes for addressing rhetorical decisions in activist contexts. In addition to these pedagogical implications, this study demonstrates the importance of investigating the potential of non-digital mediums for making activist arguments.

Civic Contribution is the Icing on the Cake

Effective epideictic rhetoric can assist a rhetor in the pursuit of social change. In “The Public Value of Epideictic Rhetoric” (1996), Cynthia Sheard demonstrates that one of the roles of epideictic rhetoric is to invoke and therefore inspire the values of a community (771). For example, when a eulogy praises the recently deceased for his generosity and open-mindedness, it asserts that these are admirable values and persuades the audience to be generous and open-minded as well. Sheard claims that by praising or blaming certain values, epideictic rhetoric can stimulate change in a community.

Extending Sheard’s claims about the civic potential of epideictic rhetoric, other scholars have noted historical examples of how epideictic rhetoric was used to challenge norms and promote new community values, rather than affirm the prevailing cultural norms. In “Inventing Sacagawea: Public Women and the Transformative Potential of Epideictic Rhetoric” (2009), Cindy Koenig Richards uses the example of the commemoration of a statue of Sacagawea at the 1905 World’s Fair by members of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Noting that Sacagawea’s contributions to the Lewis and Clark expedition had been largely ignored until a 1903 book publication, Richards argues that NAWSA made an epideictic argument that not only promoted the suffragist community’s values but also attempted to challenge normalized racism, with a statue and dedication ceremony that “presented an American Indian woman as an icon of American identity and progress” (p. 3).

Then, using the example of an American president’s commencement speech, in “John F. Kennedy at American University: The Rhetoric of the Possible, Epideictic Progression, and the Commencement of Peace” (2014), Denise M. Bostdorff and Shawna H. Ferris claim that epideictic rhetoric can achieve the opposite of praising cultural norms and rather “transform listeners’ perceptions of reality” (p. 409). Bostdorff and Ferris describe how President John F. Kennedy used his 1963 commencement speech at American University to appeal to his listeners to consider the possibility of peace (and more specifically, a nuclear test-ban treaty) with the U.S.S.R. Kennedy’s impassioned appeal for peace was especially significant because the success of the speech depended, in part, on his ability to override the confrontational and anticommunist sentiments of his previous public addresses. That is, Kennedy’s speech not only challenged the existing cultural norms, but it also challenged the values that he had previously helped to normalize.

Finally, in an example of activist epideictic rhetoric that blamed rather than praised, in “‘The Day Belongs to the Students:’ Expanding Epideictic’s Civic Function” (2008), Lois Agnew explains how an invited speaker for the 2003 Rockford College commencement address used the opportunity to publicly denigrate U.S. entry into the Iraq War. Agnew then describes the dramatic backlash from the audience, and how the speech and the event itself became national news items, spurring additional political debate. Agnew claims that the provocative commencement speech exemplifies the potential of epideictic rhetoric to challenge cultural norms and shared values, in an attempt to “create a new vision of the world” (p. 161).

Sheard, Richards, Bostdorff and Ferris, and Agnew demonstrate that epideictic rhetoric does so much more than reaffirm cultural values—epideictic rhetoric interrogates, contests, and even directly opposes dominant cultural values. To support this claim, these critics draw on historical examples; that is, these scholars focus on the products of different epideictic compositions. However, they do not necessarily break down the composition process itself, which I believe deserves further study.

Furthermore, two of the historical examples (the college commencement addresses) inhabited one mode: speech. The statue commemoration Richards studied can be described as a multimodal composition, given that she analyzed the rhetorical significance of both its verbal (speeches) and visual (the statue itself, draped in an American flag) components. However, Richards’s analysis of the statue commemoration does not reflect on the significance of different modes working together to create an epideictic argument.

To address these gaps in the literature, I draw on insights from food rhetoric, rhetoric of cake rituals and cake performances, and embodiment in multimodal composition to demonstrate how the multimodality of occasional cakes help craft an epideictic argument. Subsequently, I describe the process of composing an epideictic cake that performs a civic function.

Proving It’s Epideictic is a Piece of Cake

In Sheard’s article, she attributes six characteristics to epideictic rhetoric:

We can say that epideictic is educative, that it is in many ways ritualistic, that it elicits judgment, that it can initiate, support, influence, or lend closure to other modes of discourse, and we should add not only that it participates in reality at critical moments in time but that it interprets and represents one reality for the purpose of positing and inspiring a new one (790).

Each of these characteristics applies to occasional cakes. It is important to note that cakes created merely to demonstrate the decorator’s skill, such as competitive cakes, are not epideictic. For example, the cake depicted in Figure 2 might elicit judgment about the decorator’s skill, but the cake does not make an argument to praise virtue or condemn vice.

Figure 2: I made this chocolate monster for a cake decorating competition, so it is not an example of epideictic rhetoric. (Source: personal collection.)

Figure 3: To celebrate my niece on her 10th birthday, I decorated two cakes as a mustachioed robot and a plushie monster. (Source: personal collection.)

Occasional Cakes are Educative

The theme, text, and even the flavor of a cake should teach the audience about the celebratee’s interests and the reason for celebrating. This is similar to a Best Man’s speech, which typically includes personal anecdotes about one or both of the newlyweds, before praising virtues apparent in the newlyweds’ relationship. Like a Best Man’s speech, the cake in Figure 3 is educative. The text and the symbolism of the balloon and gift indicate that a birthday is being celebrated. Furthermore, the absence of a licensed character (common on children’s birthday cakes) and presence of a mustache and robot demonstrate my niece’s creativity and maturing affection for alternative pop culture trends. Finally, the cakes were chocolate, which teaches the primary audience (i.e., the partygoers at my niece’s first sleepover party) something about my niece’s preferences and personal taste.

The connection between the educative possibility of food and the representation of an individual’s values is a common theme of food rhetoric scholarship. For example, in the foreword to The Rhetoric of Food: Discourse, Materiality, and Power(2012), Raymie E. McKerrow describes how even the way one speaks about food can educate one’s audience about his or her values: “[H]ow we frame our conversations about food...conveys a wealth of information about who we are” (p. xii). Likewise, one’s food choices, such as meat consumption or a vegan lifestyle, also communicates information about one’s values, although McKerrow warns against making imprecise assumptions (p. xii).

Thus, in Political Appetites: Food as Rhetoric in American Politics (2013), Alison Perelman discusses how Governor Mitt Romney’s campaign staff and national news media monitored the Republican presidential nominee’s eating habits to identify potential insights into his cultural and spiritual values, during both the 2008 and 2012 primaries. The Romney campaign tried to represent the candidate as an all-American man, and presumably, the cultural standard for an all-American man involves unhealthy eating choices. Despite the campaign’s efforts, journalists reported that the candidate maintained a healthy diet; even when he ordered unhealthy food items, he modified them to reduce the calories, such as removing the skin from fried chicken and the cheese from pizza (p. 136). The candidate’s avoidance of caffeine was also of interest to the general public, because any consumption of caffeine signaled the extent to which Romney did or did not conform with the requirements of his Mormon religion (p. 136). As food items, cakes also possess this potential to educate an audience about the values of the people receiving and serving the cake, even apart from the potential of occasional cakes to communicate a specifically epideictic message.

Occasional Cakes are Ritualistic

My mother’s insistence that birthdays need cakes is hardly unusual. In popular culture, cakes are frequently associated with celebrating milestone events in a person’s life, such as birthdays, weddings, graduations, anniversaries, and retirement, as well as for celebrating the milestones of organizations. There are rituals for presenting and serving cakes at these events, such as newlywed couples cutting their own cake and smash cakes for first birthdays. Entire movie plots are written around the rule that you make a wish when you blow out the candle and if you tell anyone, it won’t come true.[2] In addition to cultural traditions, people bring their own rituals to celebratory cakes. I know a family who has pineapple-upside-down cake for every single birthday. I have adopted my parents’ tradition that after the birthday person blows out his or her candles, you re-light one candle for the youngest person in the room to extinguish, to resounding applause.

One of the foundational works on the development and meaning of cake rituals comes from an analysis of wedding cake traditions. In “The Wedding Cake: History and Meanings” (1988), Simon Charsley describes how rituals come to exist and to acquire different meanings and interpretations during their existence. Charsley challenges the assumption that something as luxurious as wedding cake must descend from upper classes, appropriated by average people wishing to imitate royalty. In addition to the cake itself, which “originated amongst country and small-town folk” and was later popularized by Queen Victoria’s family, the ritual of cutting the cake had a humble background, with “roots in the urban middle classes of the nineteenth [century], before progressing through the entire society, upwards as well as downwards in the social scale” (p. 239).

Charsley also describes how these rituals evolve to take on new meanings in different times, and most importantly, he notes that it is the materiality and spatiality of cakes that influenced changes in the rituals and their interpretations. For example, the original eighteenth-century recipe for wedding cake icing was white because its ingredients happened to produce a white color; only later did Victorian society associate the white color of the icing with virginal purity. In another example, the cutting of the wedding cake, which originally was conducted by the bride alone as part of a magic ritual, eventually required the assistance of a second person (i.e., the groom), because the increasingly elaborate constructions of wedding cakes made it too difficult for one person to cut and serve the cake by herself. The ritual of cutting the cake as we know it today was born from an entirely different ritual modified due to material constraints and was then ascribed a new interpretation, as the newlywed couple’s “first joint task in life” (p. 240). This will become relevant again in an observation from my case study, when spatial constraints lead to a spontaneous modification of cake rituals.

Occasional Cakes Elicit Judgment

Cakes elicit judgment about both the execution of the cake and the celebratee. For example, at the end of each episode of the reality television show Cake Boss, the team of bakers reveals a cake worth thousands of dollars and multiple hours of labor, and without fail, the cake elicits gasps of awe and cheers from the client and the client’s guests. Many episodes of Cake Boss also demonstrate the extent to which a cake elicits judgment about the intended recipient, such as when the bakery makes a large treasure chest cake for two children who “are a big treasure” (TLC). Posts on Cake Wrecks, where the products of alleged professional decorators are mocked, are another example of how cakes elicit judgment (http://www.cakewrecks.com/).

In a somewhat disparaging example of the blame function of epideictic occasional cakes, in “Nutritionally ‘Empty’ but Full of Meanings: The Socio-Cultural Significance of Birthday Cakes in Four Early Childhood Settings” (2015), Deborah Albon describes how parents’ requests to bring birthday cakes to their children’s nurseries (similar to American daycares or preschools) elicited judgments from the nurseries’ staff. Especially when the requests came from working-class families, Albon found that the nurseries’ staff forbade homemade cakes (on the grounds of “poor hygiene” in the homes) and criticized the flavor of storebought cakes and other aspects, such as nearness of expiration date (p. 84). Yet, Albon found that all of the staff she interviewed saw the birthday cake “as central to birthday celebrations” (p. 85, emphasis hers). In fact, Albon found that some staff were “particularly vehement in the belief that birthday cakes have a symbolic importance that should not be ignored” (p. 86). One might assume that this “symbolic importance” is the epideictic message that the celebratee be so honored.

Occasional Cakes Initiate, Support, Influence, or Lend Closure to Other Modes of Discourse

If you walk into a conference room where a cake on the table says “Congratulations Rita! Best of Luck on Your Retirement,” you will likely locate Rita and tell her congratulations and wish her luck. This is an example of how a decorated cake initiates (if you weren’t planning to say it already), supports (if you were planning to say it), or influences (maybe you don’t like Rita, but you were moved to deliver one final, good-natured gesture) further discourse.

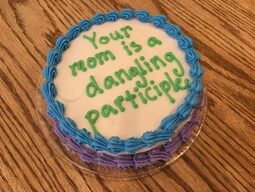

As demonstrated in the example of school staff judging the ability of working-class families to provide birthday cakes, not only can occasional cakes demonstrate the praise function of epideictic rhetoric, but they can also indicate blame. Insult cakes and troll cakes are examples of cakes that highlight a negative quality of the recipient in order to initiate, support, influence, or lend closure to a mode of discourse (Yates; http://www.trollcakes.com/). For example, the cake depicted in Figure 4 is a troll cake, which highlights one of many indecorous comments made by one of my copyediting clients. I decorated and delivered this cake in an attempt to influence a positive change in my client’s style of discourse for responding to editors’ comments.

Figure 4: This cake highlights an indecorous comment made by a copyediting client. (Source: Personal collection.)

One surprising example of how occasional cakes might initiate discourse is found in Albon’s observations of birthday cake practices in British nurseries. Albon observed many young children regularly playing a game in which they imitated the ritual of presenting a birthday cake (made from “dough, clay, [or] damp sand”), singing “Happy Birthday,” and blowing out candles made from items “such as sticks or pencils” (p. 88). Albon found that the games involved many multilingual children, who “delighted when their name was sung in the ‘Happy Birthday’ song,” in part because their peers had practiced learning and pronouncing their names (p. 88-89). Not only did the performance of actual birthday cakes bring the children together to support one discourse—the honoring of the child being celebrated—but the imitation of that performance had also initiated new discourse between students and helped in the formation of personal relationships.

Occasional Cakes Participate in Reality at Critical Moments in Time

As previously discussed, cakes are commonly used to celebrate milestone events, and they “participate” in a number of ways. At a minimum, cakes are enjoyed visually, often as the centerpiece of a party’s decorations, and then by taste, typically as the grand finale of a meal. The multisensory experience (e.g., by sight, touch, and taste) of producing and receiving cake is part of the cake’s rhetoric, as an embodied multimodal composition.

In the introduction to the edited collection Composing Media Composing Embodiment, Anne Francis Wysocki discusses some of the values of this type of embodied multimodal composition. Wysocki explains how embodiment involves both the active experience of a composition by its producer and the passive experience of a composition by its audience. Wysocki claims that multisensory compositions are necessary, because it is through our bodily senses that we know the world: “[E]mbodiment is an ongoing process to which we need attend and for which we need engagement with a range of media” (p. 22).

By inhabiting more than one mode and engaging multiple senses, epideictic occasional cakes invite both their producer (i.e., the cake decorator) and their audience (i.e., the celebrated and partygoers) to experience the world in a particular way, within a specific space and time.

Activist Occasional Cakes Represent One Reality and Inspire a New One

Given how occasional cakes share every other characteristic of epideictic rhetoric, how does the last part of Sheard’s definition apply? How does my niece’s plushie monster and robot cake “interpret and represent one reality for the purpose of positing and inspiring a new one”? I argue that it does not, and that many occasional cakes do not inspire new realities either. However, in a different context—in which a celebratee’s reality was that the voice of the majority questioned the celebratee’s self-worth—one could argue that the celebratee’s cake—a multimodal argument to praise and value the celebratee—did propose a new reality. This connection between a shift in context and a shift in rhetorical potential illustrates the importance of the activist component. To support this claim, I offer my observations from a personal case study in which I worked with a charitable nonprofit, Extra-Ordinary Birthdays, to decorate birthday cakes for children experiencing homelessness.

Let Them Eat Self-Affirming Cake

I began decorating cakes for Extra-Ordinary Birthdays (EOB) in February 2015. Founded by Schinnell Leake (L’Oreal’s 2015 Woman of Worth), EOB hosts birthday parties for children living in homeless shelters and domestic violence shelters. On its website, EOB describes its mission as one to “transform the lives of homeless children by creating personalized birthday parties that make them feel valued and inspire moments of delight in their lives” (http://www.extraordinarybirthdays.org/). These personalized parties center on a theme chosen by the birthday child, and every party includes decorations, games and activities, gift bags, snacks, a gift, and a cake.

I first began to decorate cakes that “inspire a new reality” after speaking directly with Ms. Leake, an exuberant and compassionate woman whose passion for birthday celebrations rivals my mother’s. Ms. Leake added me to her list of volunteers, and a couple of days later, I received an email with the names, ages, and theme requests of two girls: a two-year-old with a Minnie Mouse party and a ten-year-old with a Frozen party.[3] The process of designing, shopping for, baking, decorating, and delivering the cakes gave me considerable insight into the many rhetorical decisions involved in making occasional cakes with an activist component.[4]

Designing

I started designing the cakes about a week before the parties. I wanted to do something the children would recognize easily, so I went with a full-body Minnie Mouse and as much of Elsa as I could fit on the face of an eight-inch round cake. The size of the cakes was a challenge. Characters are much easier to draw (or more specifically, pipe) on larger surfaces, which is why I typically do them on a 13-inch by 9-inch rectangular cake. However, Ms. Leake specifically asked me to keep the size small. She told me that the families were not allowed to bring leftover cake back to their rooms. What she did not have to say, was that bringing more cake than they could eat, knowing the leftovers would be thrown out, was disappointing at best and insulting at worst. Although larger cakes might have yielded more aesthetically pleasing designs, the smaller eight-inch rounds were absolutely necessary to appropriately celebrate and honor the recipients without causing undue sadness.

I searched online for images of the two characters to use as guides, and after browsing through multiple versions of coy Minnies and sultry Elsas, I decided on an open-armed Minnie reaching up for a hug and an open-handed Elsa creating magic snow. Rather than designing cakes in which the depicted female characters exist merely to be gazed upon, I wanted these characters to demonstrate values worth emulating: a welcoming and kind Minnie Mouse, a strong and powerful Elsa.

Figure 5: Both cakes included representations of the birthday child’s requested theme (left, Minnie Mouse; right, Frozen), the child’s age, and the child’s name (obscured here, see Footnote 3). (Source: personal collection.)

Shopping for Supplies

On a snowy Saturday morning, five days before the birthday parties, I went shopping for cake boxes and new dyes. I found some snowflake rings to add to the Frozen cake, figuring that in addition to decorating the cake, the rings could be repurposed as souvenirs for the ten-year-old birthday child and her friends. I could not buy a similar trinket for the two-year-old birthday child, because every Minnie Mouse item was a choking hazard for her age group. I almost purchased fancy birthday candles, but I decided against it because I did not know whether lighting candles in the shelter was allowed.

Even though the cakes had not yet materialized, something as simple as shopping for cake supplies (an activity I had completed many times before) forced me to consider how the materiality and the spatiality of the cakes factored into the composition process. By decorating cakes in a new context, I was facing rhetorical decisions I had not actively deliberated before. Just as Ms. Leake’s request to make a small cake made me consider how a waste of cake can offend, the wide variety of disposable and dangerous cake decorations at the cake supply store made me actively consider the appropriateness of my purchases for these and future cakes.

Baking

On Sunday, with the help of my two-year-old daughter, I made four round yellow cakes from two cake mixes. About five minutes after I put the cakes in the oven, I remembered that the ten-year-old birthday child had requested a chocolate cake. If this cake had been for someone in my family, I might have considered giving her a yellow cake anyway. However, I realized that if the message of the cake was that she mattered, that her wants and needs mattered, I needed to give her the flavor she explicitly asked for. I baked a chocolate cake on Monday.

Decorating

On Monday evening, I decorated the Minnie Mouse cake, and on Tuesday evening, I decorated the Frozen cake (see Figure 5). I piped the designs in homemade buttercream frosting, and each cake was done in about an hour and a half.

As a single mother with a two-year-old and a nine-month-old, I had to plan childcare for both evenings of cake decorating, and on both evenings, two of my favorite babysitters volunteered their time to watch my children. Their generosity reminded me of the community aspect of civic contributions. As I attempted to assist other parents (the vast majority of which are also single mothers) in celebrating the lives of their children, members of my community offered their assistance to me. Their rhetorical decision, to not charge me for their time, factored into the composition of this multimodal activist assignment in an unanticipated and delightful way.

Delivering

When I arrived at the shelter (a modified elementary school) on Wednesday night, Ms. Leake buzzed me in and led me to the cafeteria, where a handful of volunteers were inflating balloons, smoothing out plastic tablecloths, and crumbling up sheets of paper for a snowball fight game. Ms. Leake showed me exactly where to place each cake, invited me to attend or assist with the parties, and handed me an EOB apron and a snack tray to assemble.

As two groups of about six children arrived, and as the party activities began, I was surprised to notice no difference between the actions of these partygoers and the actions of any other group of children I have ever seen at a birthday party. The setting of the party seemed to have zero influence on the partygoers’ abilities to fully partake in the Frozen- and Minnie-Mouse-themed crafts, games, and snacks, complete with the chatter, joking, shrugging, smiles, cries, pouts, and laughter typical of children’s birthday parties. The only time the circumstances interfered with the celebration was the shelter-enforced restriction against lighting birthday candles (“They used to allow candles, but not anymore,” Ms. Leake informed me), but we sang “Happy Birthday” loudly, and the older of the two birthday girls proudly cut and served her own cake.

In an hour and a half, the kids returned to their rooms, and in Ms. Leake’s de-brief to the volunteers, she made two comments that referenced the epideictic nature of the cakes: “Having a cake with their name on it–that’s huge” and “She asked for chocolate and she got it.”

I would later learn that personalization is a top priority for EOB parties, because the valuing of a child’s “personal” preferences represents valuing of the child him- or herself. In this context, “personalization” is akin to “humanization.” This is especially important for a marginalized group that experiences dehumanization whenever their challenges are overlooked or their very existence is ignored in either public discourse, such as policy deliberations (Kaufmann, 2013), or in private discourse, such as in-person encounters (Waldholz, 2015).

Reflection

In addition to the cakes’ contribution to the overall personalization of the EOB parties, I contend that the cakes were epideictic in the extent that they met each component of Sheard’s definition of the function of epideictic rhetoric:

- The cakes were educative. We learned the celebratees’ favorite TV show and film, and their favorite flavors.

- The cakes were ritualistic. Friends and family sang “Happy Birthday” before serving the cake. To replace the denied ritual of blowing out birthday candles, one of the celebratees responded to the spatial constraints by adapting the previously discussed ritual associated with wedding cakes—cutting her cake.

- The cakes elicited judgment. Partygoers complemented the appearance and taste of the cakes, and more importantly, everyone praised the birthday girls for providing the occasion for having a party and a birthday cake, that is, for being born and being an important part of their friends’ and families’ lives.

- Similarly, the cakes supported and initiated discourse, in that everyone who saw the cakes wished the girls a happy birthday, including people who lived or worked in the shelter but did not attend the party.

- Finally, the cakes not only participated in reality at a critical moment in time but also represented one reality while inspiring a new one. The cakes participated in the event by contributing to the party decorations and activities, which softened but did not obscure the “reality” of the homeless shelter. The cakes represented one reality, in which a personalized birthday cake is a stranger’s donation, and inspired a new reality, in which having a home enables the baking and decorating of homemade cakes.

This final point is especially important, because it demonstrates how these birthday cakes are epideictic in more than one way. In addition to communicating to the birthday children (as well as their guests) that their lives are worth celebrating, the cakes also communicate to the parents of the birthday children that their community recognizes their challenges but also respects them as parents.

In their research of birthday celebrations among low-income families and mothers receiving government assistance, Jaerim Lee, Mary Jo Katras, and Jean W. Bauer (2008) and Addy Bareiss, Alicia Woodbury, and Alesha Durfee (2009) describe the importance of this reaffirmation for the parents. Lee et al. claim that by enacting culturally significant birthday celebration rituals, families facing financial insecurity aim to “show their children that they are important…that their families can celebrate their birthdays just like other families…” (p. 547). They use a variety of strategies and resources to provide their children with themed parties, gifts, and decorated cakes, specifically to positively impact the child’s sense of self-worth, “to infuse their children with a feeling of normalcy” (Lee et al., p. 547). Lee et al. describe the birthday cake in particular as one of the “main ritual artifacts of children’s birthday celebrations” (p. 547).

For these families, birthday celebrations are just as important to the parents’ sense of self-respect as they are to the child being celebrated. Bareiss et al. describe how parents, specifically mothers, who receive government assistance face a social stigma: “Popular scripts of ‘welfare mothers’ collapse the rich and difficult experiences of poor mothers….[N]ot only must they meet the ideals of cultural motherhood, they must also successfully resist being labeled a ‘bad’ mother” (p. 87). Bareiss et al. explain how women in this situation perceive the ability to host birthday celebrations for their children, in accordance with cultural norms, as necessary for overcoming this stigma. In interviews with mothers receiving government assistance, the authors noted that the birthday cake “was often described as essential” to the birthday celebration (p. 90).

Birthday cakes are certainly not essential from the standpoint of nutritional sustenance, and the extent to which birthday cakes are essential to birthday parties stems from a class-based cultural standard. Yet this cultural standard is so ubiquitous, that most children, regardless of their life circumstances, expect to see a birthday cake at a birthday party. I was reminded of this the last time I delivered a cake for an EOB party, when a young child briefly poked her head in the door, and then ran back to the designated party room, announcing to the guests: “The cake is here.” Note: not a cake, but the cake. There seemed to be no doubt for this young child that the birthday party she was about to attend would feature a birthday cake. Although a cultural studies framework might critique the proliferation of such a superfluous, class-based object as a decorated cake, the fact remains that birthday cakes communicate a fairly universal epideictic message that vulnerable populations deserve to hear.

Multimodality Takes the Cake

As the results of the case study demonstrate, epideictic cakes can serve a civic function well, “as a means of envisioning and urging change for the better” (Sheard, 788). However, to expand on Sheard’s claim that epideictic rhetoric can serve a civic function, I contend that multimodal epideictic rhetoric is particularly well suited to communicating activist messages.

Multimodal composition is particularly advantageous in rhetorical arguments that represent marginalized groups, anyone who is seldom heard and often silenced. For example, in “Detroit and the Closed Fist: Toward a Theory of Material Rhetoric” (1998), Richard Marback describes how the public sculpture, “Monument to Joe Louis,” is just as much a reminder of “the struggles of African-Americans and the continuing crises of racism” as it is a tribute to one African-American national hero (p. 78). Drawing in part on parallels between the monument and the closed fist associated with Black Power activists, Marback notes how the multimodality—specifically, the “corporeality, spatiality, and textuality” (p. 88)—of the sculpture is part of its rhetorical argument: “The fist thrust horizontally in midair evokes experiences and materializes conditions of contemporary struggles for meaning and value in city life” (p. 85). Likewise, Jamie White-Farnham describes in “Changing Perceptions, Changing Conditions: The Material Rhetoric of the Red Hat Society” (2013) how members of the Red Hat Society, a social club for aging women, wear handmade red hats and other dramatic regalia during all of their public excursions, to not only address but also intervene in “the marginalization or invisibility of aging women” (p. 475).

Connecting activist rhetoric and multimodal composition with epideictic rhetoric, Matt Ratto and Megan Boler describe the activist potential inherent in multimodal composition (referred to as “critical making”) in a way that resembles Sheard’s definition of the function of epideictic rhetoric, to represent one reality and inspire a new one: “[S]haping, changing, and reconstructing selves, worlds, and environments in creative ways...challenge[s] the status quo and normative understandings of ‘how things must be’” (5). It is worth noting that the multimodal and activist arguments featured in DIY Citizenship utilize mediums that the average person, acting as an activist citizen, can manipulate to construct or support an argument. The baking and decorating of occasional cake is such a medium.

There are at least two ways to understand how multimodal epideictic arguments function more effectively than epideictic arguments comprising one mode, such as speech or text alone. First, there is the simple idiom, “talk is cheap,” or as Steve Mann elaborates in “Maktivism: Authentic Making for Technology in the Service of Humanity”: “In short, thoughts matter, but also matter matters” (p. 31). You can tell homeless children that their birthdays are worth celebrating, or you can help ensure that they have a birthday celebration. One requires a lot more effort than the other, but the extra effort guarantees that an event occurs along with a long-lasting memory, for the benefit of the children and their parents.

A second point to consider, raised by Marback, is that material rhetorics demonstrate “the irreducibility and interdependence of corporeality, spatiality, and textuality” (p. 88). As rhetorical and multimodal objects, birthday cakes made for children experiencing homelessness likewise demonstrate this connection. The cakes are corporeal to the extent that they feed people whose access to food has been rendered unpredictable. The cakes are spatial in that they help to remake the space in which they are presented and consumed—a homeless shelter, many of which forbid fraternization between families outside scheduled mealtimes—into a space of celebration, friendship, and fun. The cakes are also textual, in so far as they are inscribed with a message, “Happy Birthday,” and personalized with the recipient’s name and age. The ultimate message of these cakes—that the recipients deserve a happy day celebrating them, despite the circumstances that might prevent it—is stronger because of the way these three things—corporeality, spatiality, and textuality—work together.

Two drawbacks of cakes as a medium for activism are their temporal nature and that their intended audience is fairly private. This is alleviated somewhat by the distribution and publicizing of photographs of cakes, such as on EOB’s website and Facebook page (Figure 6). It is primarily through this second distribution of the message that it achieves its activist function: inspiring others to contribute time, money, or awareness to the issue that homeless children deserve and need to be celebrated.

Figure 6: A screenshot of EOB’s Facebook page shows the organization’s active attempts to publicize the issue of homelessness. The page is updated daily, with pictures of EOB parties, spotlights on volunteers, and articles on homelessness and compassion.

Implications for Pedagogy

In the introduction of Toward a Composition Made Whole, Jody Shipka argues for using multimodal discourse in composition courses to emphasize what can be learned from the process of composing, rather than focusing solely on the outcome. She states, “[C]omposition is, at once, a thing with parts—with visual-verbal or multimodal aspects—the expression of relationships and, perhaps most importantly, the result of complex, ongoing processes that are shaped by, and provide shape for, living” (Shipka, 17). As I demonstrated in the previous section, providing a cake for a celebration is multimodal in that it involves corporeal, spatial, and textual modes of discourse. As I described in the account of my case study, the process for providing such a cake involves multiple steps, each of which requires deliberate rhetorical decisions. Despite the number of steps in the process, baking and decorating a cake requires little to no prior experience, and because the materials are comparatively inexpensive, the costs of the project are minimal. (That said, you do need access to a working oven). The ease of access with this particular medium makes it a potential multimodal student project for examining epideictic rhetoric and its activist potential.

The most important aspect of such an assignment is that students provide a cake for someone they do not know personally. This ensures that students actively deliberate rhetorical decisions in the “composition” process, rather than go with what they intuitively know to be true about the individual’s preferences. In addition to providing cakes for families experiencing homelessness, other situations that may benefit from student-created and -donated cakes include birthdays for critically ill children, birthdays in a retirement home, or other milestones, such as “welcome home” cakes for returning veterans.

Whoever students choose to praise (or perhaps, in some cases, blame), in order to achieve the activist potential of the assignment, it is essential that students plan cakes that fulfill the final part of Sheard’s definition of the function of epideictic rhetoric, “interpret[ing] and represent[ing] one reality for the purpose of positing and inspiring a new one.” In addition to my previously described case study, testimonials on the website icingsmiles.org demonstrate how decorated cakes can inspire new realities. Written by family members of critically ill children who received personalized birthday cakes through the nonprofit Icing Smiles, many of the comments emphasize the importance of celebrating these children outside the context of their daily medical challenges, to, in the words of one grandparent, “enjoy a little bit of every day life” (What others are saying, 2017).

After students identify a purpose and audience for their epideictic activist cake, they will have to consider a wide range of rhetorical decisions. Issues that might have seemed insignificant in a different context will suddenly require deliberate analysis and inquiry of the medium itself and its cultural significance. For example, although it might seem like a minor concern, the decision to provide a whole cake or cupcakes is rhetorical. Ms. Leake of EOB has specific guidance on this issue: Provide a whole cake whenever it is logistically possible. Cupcakes are somewhat easier for traveling, storage, and serving, but whole cakes provide at least two advantages over cupcakes: The larger surface area affords more complex designs, and the unity of one whole cake encourages partygoers to gather around the celebratee, especially for the singing of “Happy Birthday.” However, as first birthday smash cakes become a more popular ritual, EOB has made exceptions for cupcakes on first birthdays, because a cupcake can function in the place of a small smash cake. Considering these types of concerns about the medium itself will force students to deliberately analyze how different mediums perform materially and spatially as well as culturally.

Activist epideictic cake assignments will also require students to consider issues of ethics. For example, students must consider the extent to which cake is an appropriate medium for celebration in different contexts. In the case of providing a birthday cake for a child experiencing homelessness, how does one weigh the ethics of celebrating the life of a child against the ethics of providing a relatively high-calorie food with little nutritional value to a community that is food-insecure? (To balance this particular concern, Ms. Leake ensures that every EOB party serves healthy snacks, such as fresh fruit and vegetables, instead of other common party snacks, such as potato chips or chocolate candy.) Especially for assignments with an activist component, it is essential that students consider not only the rhetorical implications of their multimodal compositions but also the ethical implications.

Finally, asking and answering questions about multimodality, culture, and ethics in the context of occasional cakes can help students think about the composition process, epideictic rhetoric, and activism in new and memorable ways, in part because cake is not a digital medium. In “Beyond ‘Digital’: What Women’s Activism Reveals about Material Multimodal Composition Pedagogy” (2017), Jessica Rose Corey finds, after analyzing 74 t-shirts decorated as part of the activist Clothesline Project, that the vast majority of her students prioritized the textual over the visual, seemingly unaware of the affordances of visual rhetoric. Corey suggests that to help students understand the importance of aesthetics for rhetorical arguments, the teaching of multimodal composition must consider some of the advantages of tangible mediums over digital mediums. Given that occasional cakes rarely display more than four or five words of text and are material and spatial as well as visual, the tangible nature of cakes might offer activist multimodal composition a tangible solution.[5]

Conclusion

In this article, I have argued that occasional cakes are an example of epideictic rhetoric, and because they are both epideictic and multimodal, they are an appropriate medium for communicating activist messages, especially for representing the values of vulnerable or marginalized groups. Further research in this area might investigate other mediums that have similar capability, building on a growing body of work that combines the benefits of multimodal composition with the benefits of activist composition.

I wish to make one final note to advocate for the making of activist, epideictic, occasional cake. At times, it seems as though there is no end of issues to argue about, and yet, it can also seem impossible to achieve a productive dialogue between those of different opinions. Some people choose to scream or yell in frustration, in the face of their opponent, in all caps in a Facebook comment, into a pillow, into the void (Mazza, 2015), or into a sheet cake (Butler, 2017). Rather than merely yelling (or yelling into a cake), I recommend that people recognize cake as a medium that can make a personal, productive, activism possible when we actually do something with it. When someone needs to receive a crucial message of affirmation, perhaps make that person a cake—or a quilt, or a card, or whatever multimodal message is most fitting—to remind them: I value you as a human being, your life is important, and the world is better for having you. Enjoy.

Acknowledgements

I am full of gratitude and admiration for Schinnell Leake, and I thank her for allowing me to work with Extra-Ordinary Birthdays and for her review of this article. In addition to thanking Schinnell Leake, I also thank Steve Holmes, the JOMR editors, and two anonymous reviewers for providing immensely helpful feedback on different iterations of this article.

Endnotes

[1] Judicial rhetoric is often referred to as “forensic” rhetoric; however, in his translation of Aristotle’s On Rhetoric (2007), George A. Kennedy recommends avoiding the use of “forensic,” as an inappropriate interpretation (p. 47).

[2] According to Marietta Rusinek (2012), the ritual of lighting candles on cakes goes back to the ancient Greeks, who made round cakes to resemble a full moon in honor of the goddess Artemis, adding candles so the cakes resembled the Moon’s glow as well as its shape.

[3] To respect the cake recipients’ privacy, their names have been omitted from this text and obscured in photographs of the cakes.

[4] Ms. Leake and I decided against interviewing or surveying the birthday children or their families, because we did not want to distract from the celebrations in any way. Therefore, the following narrative draws from my personal observations and not from the experience of the people being celebrated. Future research in this area might seek to address this limitation and better represent the voice of a marginalized group.

[5] In her discussion of Freire in “The Rhetorician as an Agent of Social Change,” Ellen Cushman defines “tangible” as “synonymous with activism” (p. 24).

References

Agnew, L. (2008). “The day belongs to the students”: Expanding epideictic’s civic function. Rhetoric Review, 27(2), 147-164.

Albon, D. (2015). Nutritionally “empty” but full of meanings: The socio-cultural significance of birthday cakes in four early childhood settings. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 13(1), 79-92.

Bareiss, A., Woodbury, A., & Durfee, A. (2009). Children’s birthday parties: Welfare and constructions of motherhood in the United States. Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering, 11(2), 85-97.

Bostdorff, D., & Ferris, S. (2014). John F. Kennedy at American University: The rhetoric of the possible, epideictic progression, and the commencement of peace. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 100(4), 407-441.

Charsley, S. (1988). The wedding cake: history and meanings. Folklore, 99(2), 232-241.

Corey, J. R. (2017). Beyond “digital”: What women’s activism reveals about material multimodal composition pedagogy. The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, 1(1), 58-71.

Cushman, E. (1996). The rhetorician as an agent of social change. College Composition and Communication, 47(1), 7-28.

Kaufmann, G. (2013, Apr. 19). This week in poverty: Ignoring homeless families. The Nation. Retrieved from https://www.thenation.com/article/week-poverty-ignoring-homeless-families/

Lee, J., Katras, M. J., & Bauer, J. W. (2008). Children’s birthday celebrations from the lived experiences of low-income rural mothers. Journal of Family Issues 30(4): 532-553.

Mann, S. (2014). Maktivism: Authentic making for technology in the service of humanity. In M. Ratto, M. Boler, & R. Deibert (Eds.), DIY citizenship: Critical making and social media. (29-47). MIT Press.

Marback, R. (1998). Detroit and the closed fist: Toward a theory of material rhetoric. Rhetoric Review, 17(1), 74-92.

McKerrow, R. E. (2012). Foreword. In J. J. Frye & M. S. Bruner (Eds.), The rhetoric of food: Discourse, materiality, and power. (xi-xiv). Routledge.

Perelman, A. (2013). Political appetites: Food as rhetoric in American politics (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. (907)

Ratto, M., & Boler, M. (2014). Introduction. In M. Ratto, M. Boler, & R. Deibert (Eds.), DIY citizenship: Critical making and social media. (1-27). MIT Press.

Richards, C. (2009). Inventing Sacagawea: Public women and the transformative potential of epideictic rhetoric. Western Journal of Communication, 73(1), 1-22.

Rusinek, M. (2012). Cake: The centrepiece of celebrations. In M. McWilliams (Ed.), Celebration: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2011 (308-315). Prospect Books.

Sheard, C. M. (1996). The public value of epideictic rhetoric. College English, 58(7), 765-794.

Shipka, J. (2011). Toward a composition made whole. University of Pittsburgh Press.

TLC. (2010). A princess, a pirate and a perplexing arch [Television series episode]. In High Noon Entertainment, Cake boss. Hoboken, NJ: Carlo’s Bakery.

Waldholz, C. (2015, Feb. 25). Watch what happens after homeless child is ignored in freezing cold for hours. Life & Style.Retrieved from http://www.lifeandstylemag.com/posts/watch-what-happens-after-homeless-child-is-ignored-in-freezing-cold-for-hours-52491

White-Farnham, J. (2013). Changing perceptions, changing conditions: The material rhetoric of the Red Hat Society. Rhetoric Review, 32(4), 473-489.

What others are saying about us. (2017). Icing smiles. Retrieved from https://www.icingsmiles.org/what-others-are-saying-about-us/

Wysocki, A. F. (2012). Introduction: Into between—On composition in mediation. In Arola, K. L., & Wysocki, A. F. (Eds.), Composing media composing embodiment (1-22). University Press of Colorado.

Yates, J. (2015, Mar. 24). 8 insult cakes that backfired. Cakewrecks. Retrieved from http://www.cakewrecks.com/home/2015/3/24/8-insult-cakes-that-backfired.html