WIKIPEDIA’S GENDER GAP AND DISCIPLINARY PRAXIS: REPRESENTING WOMEN SCHOLARS IN DIGITAL RHETORIC AND WRITING FIELDS

Matthew A. Vetter, John Andelfinger, Shahla Asadolahi, Wenqi Cui, Jialei Jiang, Tyrone Jones, Zeeshan F. Siddique, Inggrit O. Tanasale, Awouignandji Ebenezer Ylonfoun, and Jiawei Xing, Indiana University of Pennsylvania

Wikipedia’s gender gaps, the result of a predominance of male editors and the correlating uneven participation and coverage of marginalized groups, are by now both well-known and well-documented (Cohen, 2011; Collier and Bear, 2012; Glott, Schmidt, and Ghosh, 2010; Gruwell, 2015; Wadewitz, 2013). This article seeks to interrogate these gaps in coverage as they manifest in discipline-specific representations, especially representations related to the academic fields of computers and writing, digital literacy, and digital rhetoric. Preliminary analysis of articles related to these fields demonstrates a severe lack of coverage which, given these fields’ attention to digital literacies, should be improved. This article employs a bibliometric method of citation analysis (Eyman, 2015; Kaur, Radicchi, and Menczer, 2013) across five Wikipedia articles related to these fields to show how the gender gap manifests in the absence of cited research by non-male scholars. To address these content gaps, co-authors of this article move beyond analysis to define and engage in acts of critical digital praxis within Wikipedia, editing the encyclopedia to improve representation of women and women’s research in computers and writing and digital rhetoric fields. Descriptions of such editorial work and its implications, furthermore, provide a model for disciplinary praxis, and graduate pedagogy, in which authors work together to engage in the critique and remediation of Wikipedia’s disciplinary content and gender gaps. As a larger example of critical digital analysis and participation, this article also aspires to unpack and critique the ways in which media, even those professing an open-access and democratic ethic, perpetuate social hegemonies of marginalization.

1. Introduction: The Free Encyclopedia Anyone [White Males] Can Edit

Incredibly successful in terms of size and scope, Wikipedia is often praised for its collaborative model in which self-motivated editors work through a democratic process to build a global repository of knowledge. However, Wikipedia’s gender gaps—the result of a predominance of male editors and the correlating uneven participation and coverage of marginalized groups—are by now both well-known and well-documented (Cohen, 2011; Collier and Bear, 2012; Glott, Schmidt, and Ghosh, 2010; Gruwell, 2015; Wadewitz, 2013).

According to a global Wikipedia survey conducted by a partnership between United Nations University and UNU-MERIT, only 13% of Wikipedia contributors are women (Glott, Schmidt, and Ghosh, 2010). While there has been some improvement in these numbers since this initial survey, more recent studies demonstrate how the lack of women editors contributes to ongoing problems of gender representation. For instance, a 2017 study of biographical articles in Wikipedia across languages found that only 17% of the biographies in the English Wikipedia focused on women figures (“Wikipedia Human Gender Indicator,” 2017). Wikipedia’s problematic gender politics exemplify the androcentric norms that often define online cultures and gender differences among males’ and females’ internet usage (Joiner et al., 2005). Beyond gender, Wikipedians are also typically technically skillful, formally educated, English speakers, age 15–49, from developed and majority-Christian nations (“Wikipedia: Systemic Bias,” 2017).

Speculation on why this unevenness of participation emerges varies by research and researcher positionality, and often perpetuates or advances heteronormative or stereotypical discourses. Benjamin Collier and Julia Bear (2012) posited that one possible reason for women’s reluctance to contribute might be related to a negative self-perception regarding their knowledge or ability, or a general discomfort in editing others’ work. In addition, Eszter Hargittai and Aaron Shaw (2014) found that Wikipedia’s gender bias might be caused by women’s low internet skill or lack of interest. Adrienne Wadewitz (2013), forwarding a more sensitive and nuanced perspective, argued that women—who typically are expected to perform more invisible and unpaid labor in their lives—have less free time to devote to volunteer projects such as Wikipedia.

Whatever its cause, the lack of women editors has concrete consequences regarding what’s represented in the encyclopedia. Noam Cohen (2011) tracked some of these consequences through a (somewhat heteronormative and simplistic) analysis of representation, noting that traditionally “male” subjects, such as toy soldiers or baseball cards, are often elaborated on in a lengthy article, while many subjects favorable to female audiences are underrepresented. It is important to realize, however, that gender gaps on Wikipedia have substantial, negative impacts beyond coverage of the subjects discussed by Cohen. As Wadewitz (2013) has recognized, “Wikipedia’s sexism lessens its legitimacy as a producer and organizer of knowledge” and forfeits its goals of diversity and openness.

Wikipedia’s gender problems go beyond content gaps or participation, however. The encyclopedia’s adherence to western, logocentric norms of knowledge production limit its capacity to welcome diverse epistemologies (Gruwell, 2015; Vetter and Pettiway, 2017). Unlike male editors, who tend to write more “objectively,” female editors, more often than not, engage their bodily experience in writing (Gruwell, 2015). Wikipedia fails to “accommodate feminist ways of knowing and writing” and instead facilitates “reduced notions of objectivity” (Gruwell, 2015, p. 121). More broadly, because Wikipedia fails to create a genuinely diverse and multivocal space that includes and encourages women’s voices, the encyclopedia favors gendered norms and epistemologies to the exclusion of a more democratic and multicultural encyclopedia.

In this article, we seek to interrogate Wikipedia’s gender problems further, especially as such problems manifest in discipline-specific coverage of subjects related to the academic fields of computers and writing, digital literacy, and digital rhetoric. Our focus on content related to these academic fields emerges from the situated context in which this article was envisioned and written: a doctoral-level seminar in Technology and Literacy we participated in (as professor and students) in the Composition and Applied Linguistics PhD Program at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. In addition to exploring the digital and cultural ramifications of Wikipedia’s gender gap, this project helped us achieve the objectives of learning and applying conceptual knowledge from these fields. Beyond traditional academic goals, we were also interested in engaging a mode of intellectual work that eschews normative academic spaces and epistemologies for more public, intellectual writing as digital action. The citation analysis and Wikipedia edits described in this article (as well as the drafting of this article itself) were a collaborative course assignment in English 808: Technology and Literacy. But they were also more than that: an attempt to move beyond traditional academic curricula and to practice a type of research that valorizes doing (praxis) over other types of both primary and secondary research that emphasize reviewing, collecting and analyzing as epistemological processes. Accordingly, this article—in its discussion and interrogation of Wikipedia’s disciplinary gender gap—attempts to work towards two central goals. First, our analysis of articles related to computers and writing, digital rhetoric, and digital literacy, demonstrates how the gender gap emerges and influences Wikipedia’s production of knowledge within a disciplinary ecology. Second, and in response to the findings from this analysis, we also move beyond analytics to define and engage in acts of digital praxis within Wikipedia, editing the encyclopedia to improve representation of women and women’s research within the disciplines explored.

In the following sections, we attempt to theorize the type of digital praxis we engaged in as critical reflection and action. We see such praxis as having very real material and multimodal effects, especially as we seek to remediate Wikipedia’s discursive representation of women scholars—and the accompanying cultural capital and ethos production that accompanies such representation. Our theoretical framing of this work (see Section 2) introduces and contextualizes both the analytical and reflective accounts of our engagement with digital praxis. Our procedure for a type of citation analysis (see Section 3) seeks to quantify and materialize the omission of women scholars from discipline-specific articles. Furthermore, our reflection (see Section 4) on the specific accounts of editorial praxis—what was added to specific Wikipedia articles—is also grounded in this theory. In the final section, we speculate on the implications of this type of project for graduate pedagogy. What are the challenges presented by collaborative authorship within doctoral coursework? What are the opportunities and constraints of critical digital praxis beyond Wikipedia?

2. Digital Praxis and Embodied Multimodality - Extending and Applying Theoretical Frameworks

Our examination and remediation of Wikipedia’s disciplinary gender gap engages two sets of theories in digital rhetoric: (1) what Matthew Vetter, Theresa McDevitt, Daniel Weinstein, and Kenneth Sherwood (2017) have previously termed “critical digital praxis,” a mode of rhetorical praxis in the tradition of media praxis (Fotopoulou and O’Riordan, 2014) and following a Freirean and Arendtian lineage for liberatory action (Arendt, 1958; Freire, 2007), and (2) theories on the embodied materiality and multimodality of discourse (Jones, 2010; Rohan, 2010; Selfe, 2009; Shipka, 2011; Yancey, 2014; Wysocki, 2012). This article also responds to a recent feminist rhetorical analysis of Wikipedia’s epistemological practices performed by Leigh Gruwell in which she calls for more critical pedagogical approaches to the online encyclopedia (2015).

2.1 From Media Praxis to Critical Digital Praxis

Media praxis has its roots in the philosophical and pedagogical works of Hannah Arendt and Paulo Freire, respectively, both of whom were working in a Marxist tradition. Praxis “brings together theory, philosophy and political action into the realm of the everyday” (Fotopoulou and O’Riordan, 2014, para. 3). Building upon this understanding of praxis as a form of theory into practice, Alexandra Juhasz defined queer feminist media praxis as the “making and theorizing of media towards stated projects of world and self-changing” (qtd. in Fotopolou and O’Riordan, 2014, para. 3). In other words, digital media praxis not only serves as a bridge between theory and practice but also functions as feminist action that is fluid and ever changing. Drawing from Marxist and Arendtian definitions of praxis and Juhasz’s uptake of media praxis, Aristea Fotopoulou and Kate O’Riordan (2014) reconfigured feminist media praxis as a form of political action rendered possible by digital media platforms, such as social media sites and technological tools. For instance, the online community SusNet (http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/susnet/) brings together feminist practitioners, researchers, activists, and artists, opening avenues for feminist knowledge reproduction in digital media spaces. In a similar vein, the feminist multimodal journal Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology (http://adanewmedia.org) creates a space for sustaining feminist praxis within academic discourses and communities. Recent efforts to bring media praxis into disciplinary conversations in rhetoric and composition (Vetter et al., 2017; Vetter and Pettiway, 2017) reframed the term to emphasize critical digital praxis as “a model for making writing interventions in public digital cultures in order to both better understand the writing activities of those cultures and make meaningful impressions with/in them” (Vetter et al., 2017).

In Wikipedia, critical digital praxis allows for conscious reflection and action regarding the encyclopedia’s gendered politics of access, representation, and epistemology, and how those politics shape material realities both online and offline. Citing Freire, Vetter et al. (2017) redefined praxis as “both reflection and action aimed especially at transformation” (para. 22). Such a definition moves beyond the longstanding platonic dichotomy splitting theory/thought and action/practice in western rhetoric (Arendt, 1958). Instead, critical digital praxis signals an amalgam of both thought and action. In the same work, “Critical Digital Praxis in Wikipedia: The Art+Feminism Edit-a-thon,” Vetter et al. (2017) theorized the Art+Feminism Edit-a-thon, a one-day public Wikipedia editing event specifically aimed at remediating the encyclopedia’s gender gap, as a type of critical digital praxis that “engage[s] both students and faculty in practical action that goes beyond the walls of the institution—that participates more fully in the public sphere, and that leaves a lasting impact in our (digital) world” (para. 23). Such work reminds us that Wikipedia might be one of the most effective and lasting ways in which students (and other members of a university community) can create embodied change in the digital world beyond their classrooms. It also serves as a precursor to the more sustained and disciplinary-focused mode of scholarship this article attempts to describe and theorize.

Finally, the examination of critical digital praxis as rhetorical action also opens up opportunities for recognizing the materiality and multimodality of digital media and discourse. Just as all forms of communication are both embodied and multimodal (Shipka, 2011; Wysocki, 2012), communicative praxis in digital spaces is always embodied and multimodal, and always creates specific material impacts in our everyday lives.

2.2 Multimodality, Embodiment, and Wikipedia’s Disciplinary Knowledge Production

Forging connections between multimodality and embodiment may help develop a better understanding of how Wikipedia has material consequences beyond the encyclopedia. To theorize some material aspects of Wikipedia, it might be useful to turn to Kathleen Yancey’s (2014) explanation of electronic portfolios. Yancey wrote that, “the potential of arrangement is a function of delivery, and what and how you arrange—which becomes a function of the medium you choose—is who you invent” (Yancey, 2014, p. 81, emphasis in original). Despite the focus on the ePortfolio, Yancey’s discussion also has implications for any digital archive. If we consider similar links and arrangements in Wikipedia, the encyclopedia also emerges as an important multimodal hypertext arranged to deliver particular material realities and identities.

Other scholars have explored the multimodal and multisensory nature of composition (Ceraso, 2014; Jones, 2010; Rohan, 2010; Selfe, 2009; Shipka, 2011). Cynthia L. Selfe’s (2009) history of aurality in composition referenced the importance of both metaphorical and embodied voice in composition, and her notion of voices connects to the multivocal nature of Wikipedia. Further, we might look to Shipka’s (2016) “transmodal” pedagogy that examined how writers use both modal and linguistic resources more freely. By looking at both modal and linguistic variation in texts, we might see Wikipedia as continually shaping multimodal and translingual space with embodied consequences. Jody Shipka (2011) also reminded us that “when our scholarship fails to consider, and when our practices do not ask students to consider, the complex and highly distributed processes associated with the production of texts (and lives and people), we run the risk of overlooking the fundamentally multimodal aspects of all communicative practice” (Shipka, 2011, p. 13, emphasis in original). When all texts are examined as multimodal, all texts can also be understood as sensory and thereby embodied both in how they are perceived and crafted.

Wikipedia epistemologies reflect the world outside Wikipedia by reconstructing and/or reinforcing global knowledge with both material and embodied repercussions. Matthew A. Vetter and Keon Pettiway (2017) point out that Wikipedia’s attempt to collect “‘the sum of all human knowledge’ has, so far, been a project taken on by predominantly young, white, western males” (para. 7) while also examining how a “queer approach [to Wikipedia]…is likely to be more focused on bodies, identities, genders, and/or sexualities, but can also interrogate the intersectionality of such subjects with reality, ontology, or…epistemology” (para. 3) Here, Vetter and Pettiway (2017) showed how Wikipedia references and enacts actual physical bodies and how including more diverse Wikipedians and representing people beyond those often acknowledged by “young, white, western males” has real, embodied consequences beyond the encyclopedia. To critically analyze the encyclopedia’s marginalization of non-male disciplinary scholars, and then to remediate that marginalization through inclusive efforts to better represent these scholars, as we have done in this project, is to engage in a form of critical digital praxis with both multimodal and embodied effects.

Vetter and Pettiway (2017) paralleled claims by Gruwell (2015) that while the encyclopedia is predominantly male-centric, Wikipedia can work to adopt a more inclusive and ecological model by appealing to existing epistemological processes in its ongoing production. Gruwell recognized these processes, arguing that “Most [Wikipedia] articles are written by several different authors over time, apparently privileging multiplicity and resisting the notion of single, hegemonic Truth. This kind of multivocality is, in fact, a key tenet of feminist research and writing” (p. 121). To move more concretely toward a vision of multivocality, however, we must encourage and enact both a criticality of Wikipedia’s uneven and biased production and participation by editors outside the dominant demographic. This article, and the acts of critical digital praxis it describes, represents our attempt to answer the call made by Gruwell (2015), and to enact both criticality and participation through direct editorial remediation of the encyclopedia’s gender gap. In the following section, we explore how this gap manifests in very tangible, material ways through quantitative and qualitative analysis of representative articles on topics related to digital rhetoric, computers and writing, and digital literacy.

3. Wikipedia’s Gender Gap and Disciplinary Representation

While researchers have worked to understand the extent of Wikipedia’s gender gap in terms of participation (Glott, Schmidt, and Ghosh, 2010), possible causes (Collier and Bear, 2012; Hargittai and Shaw, 2014), and systemic or structural factors (Gruwell, 2015; Wadewitz, 2013), most research on how content gaps manifest has been limited to anecdotal (and stereotypical) findings (Cohen, 2011) or more narrow studies (“Wikipedia Human Gender Indicator,” 2017). Our own analysis of Wikipedia’s gender gap as it manifests in disciplinary-specific articles is, admittedly, also limited, especially in terms of the number of articles it studies. We forward such analysis, however, with two specific goals. First, we seek to quantify and materialize the omission of women scholars in computers and writing, digital rhetoric, and digital literacy fields to help make the gender gap—what is essentially an absence—more visible. Second, we are also hopeful that our method for citation analysis, which we describe below, will be taken up in other research (both on Wikipedia and outside this context) as a way to materialize gender bias across scholarly discourses.

Our analysis of Wikipedia articles related to computers and writing, digital rhetoric, and digital literacy, began with informal examination of Wikipedia categories related to these fields (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portal:Contents/Categories). We identified the following relevant categories—Media theories, Composition, Writing, Computing and society, Digital humanities, and Rhetoric—and used a digital tool, Yanker (https://tools.wmflabs.org/pirsquared/ts_archive/mzmcbride/yanker.py/yanker.py), to identify and explore articles within these categories. Next, we manually selected Wikipedia articles that were directly and closely connected to the fields we were interested in. Finally, we identified five specific articles to study:

- Digital rhetoric (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_rhetoric),

- Multimodality (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multimodality),

- Computers and writing (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computers_and_writing),

- Digital literacy (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_literacy), and

- Media theory of composition (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Media_theory_of_composition).

To determine how these five articles represent or fail to represent non-male scholars, we employed a type of citation analysis. As an area of bibliometric research, citation analysis examines citations in scholarly articles and other texts as a means to establish and measure relations between authors, articles, texts, and academic fields. Citation analysis allows researchers to examine frequency, patterns, and graphs of citations in books, articles, and other texts which utilize similar academic systems of reference. The use of citation analysis, as a method for quantifying a text or author’s uptake by other scholars, as well as for analyzing authors’ citation networks, has increased considerably in recent years as a means to quantify researcher impact across disciplines (Kaur, Radicchi, and Menczer, 2013). Although he acknowledged its limits regarding overall consideration of a text, Douglas Eyman (2015) asserted that citation analysis constitutes the most obvious and traditional method to trace the use and value of texts. The five articles we identified in this project vary in terms of their length, comprehensiveness, and the quality level rated by Wikipedia. However, each article includes a references section from which we could examine how many non-male scholars and their works are cited in the production of the article. Ultimately, we view this type of analysis as a useful heuristic for visualizing Wikipedia’s gender gap along disciplinary lines.

In employing this method of citation analysis, we worked through the following procedures and considerations. First, we counted the total number of references used in each article, including those that led to broken links. We then counted the number of non-male authors cited in the references to identify the percentage of non-male scholars to male scholars being cited. If the same citation was included in the references more than once, it was only counted once. Next, we identified the gender of the authors cited in the references section based on their names (when obvious). If the gender was not apparent from names, we utilized the links included in the references or performed informal internet research to access authors’ websites, published articles and/or books, and identified gender based on biographical information from these sources. If there were multiple authors in one citation, we counted a non-male citation when at least one of the authors was non-male. In utilizing these methods for gender coding, we also acknowledge the problematic assumptions we are making about how individuals identify across a gender spectrum that may not be immediately visible and/or code-able by name or informal web research. However, we ultimately see such gender coding as useful in that it allows for the initial identification and analysis of patterns of citation across gender differences.

|

|

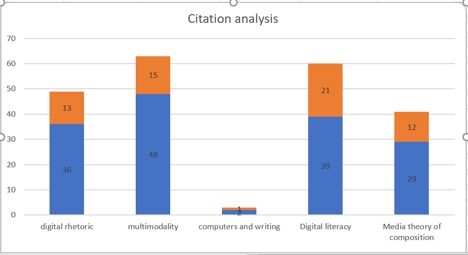

Figure 1. Graph of citation analysis shows number of non-male (orange) references and total (blue) number of references cited in Wikipedia articles on or before November 7, 2017. |

For the five articles, we counted the total number of all citations and citations from non-male scholars respectively. The total number of citations across the five articles vary, ranging from 2 to 48, depending on article development. Articles at the level of start-class (a low-quality rating according to Wikipedia’s grading system) include fewer citations, and are typically less comprehensive regarding content. For example, the article “Computers and writing” included only two citations at the time of analysis. To promote a standardized measurement, we conducted citation analysis of all articles being studied across a consistent time period, using Wikipedia’s “history” function to assess article citations on or before November 7, 2017. Since we would be editing some of these articles as part of this project, we also made sure to perform this quantitative analysis before making our own edits.

|

|

Figure 2. Citation analysis data shows number and percentage of non-male scholars referenced in 5 Wikipedia articles, and the class of each article. |

Figures 1 and 2 display the results of our citation analysis in a visual graph and quantitative data set. The article “Digital rhetoric” included 13 (or 36%) citations of non-male scholars out of 36 total references. Following this general trend, in “Multimodality” we found 15 (or 31%) of 48 references to be from non-male scholars. In “Media theory of composition,” only 12 of 29 references (or 41%) pointed to non-male scholars. “Computers and Writing” and “Digital literacy” demonstrated a more balanced relationship between total and non-male citations. The former included only 2 citations, and an even 50% split between gender identities. The latter, “Digital literacy,” showed a slightly larger percentage of non-male citations (21 out of 39, or 54%). As becomes apparent from these results, Wikipedia’s gender gap, while perhaps not as pronounced as might be expected, manifests in the percentage of non-male scholars being cited in each article. Only one article, “Digital literacy” showed a higher percentage of non-male scholars being cited. These findings help to visualize the gender gap further as it emerges within disciplinary representations pertaining to the fields of computer and writing, digital rhetoric, and digital literacy. In the next section, we describe our critical response to Wikipedia’s gender gap. We edited three of the five articles analyzed above, “Multimodality,” “Digital rhetoric,” and “Computers and writing,” with the explicit goal of increasing representation of non-male scholars by adding and representing scholarship written by women researchers.

4. Materializing New Disciplinary Representations

Wikipedia edits that work toward inclusion of non-male scholars in discipline-related articles, as a form of critical digital praxis, help materialize the scholarship of women researchers through discursive processes of representation and legitimization. In the following subsections (4.1, 4.2, 4.3), we reflect on our work with three Wikipedia articles—“Multimodality,” “Digital rhetoric,” and “Computers and writing”—reporting on their development before our edits, as well as the specific content and scholars we added to improve their representation of women researchers. In addition to these reports, we also focus on the implications of this project for disciplinary knowledge, graduate pedagogy, and disciplinary representation, respectively.

4.1 “Multimodality” and Disciplinary Knowledge

On our first read of “Multimodality,” in addition to the issues suggested by Wikipedia editors within the article itself, we found a number of specific content gaps which pointed to a lack of disciplinary knowledge. For example, in “Classroom literacy,” a subsection under “Education,” there were only two paragraphs with a brief review of literacy as defined by Gunther Kress and a list of modes utilized in contemporary class-rooms. Furthermore, the “Education” section showed an overall lack of development when it came to applying visual or multimodal literacy to educational topics. Accordingly, in “Education,” we added research by Lesley Gourlay (2010), to more clearly describe the impact of multimodal pedagogies on higher education. The section already emphasized the connection between education and multimodality, while also providing some context for classrooms. However, it did not explicitly broach the subject of higher education, so we chose to fill that gap. In the “Multiliteracies” subsection (immediately following), we added another scholar, Kathy Mills (2011), outlining her research on the importance of multiliteracies in education.

In addition to these edits, we also found that contemporary theory-based classroom practices were not included in the current version of the article. To correct this omission, we edited the article by adding two subsections, “Gaming” and “Storytelling,” which review additional applications of multimodality. In addition to these content gaps, we also attempted to improve the article’s gender gap. To accomplish this, we added research conducted by Diana George (2002) pertaining to the application of visual literacy and other mass media in English classroom and postsecondary writing instruction from 1946 to the twenty-first century. We also added Jody Shipka’s (2005) proposal for a multimodal task-based framework, emphasizing the importance of having students experience the system of delivery, reception, and circulation of their digital products.

Wikipedia is heralded as “the free encyclopedia that anyone can edit” and egalitarianism and equality are expected among editors regardless of background, gender, races, class, and ability. However, the prevalence of gender gaps among articles has ramifications for the representation of disciplinary knowledge. In working to add references and information produced by women scholars such as Gourlay, Mills, George, and Shipka, we sought to bridge the gender gap in this article, while improving its representation of disciplinary content, and answering calls made by Gruwell (2015) for more critical interrogation and participation of Wikipedia.

4.2 “Digital Rhetoric” and Graduate Pedagogy

In our initial analysis of the “Digital rhetoric” article, we noticed that less than half of references came from women or non-male authors. Accordingly, we were interested in trying to bridge this gap by bringing in more women rhetoricians and further improving the article’s development. In our assessment of the article’s needs, we identified five specific areas to contribute to, which correspond to the following sections or subsections: “Collaboration,” “Copyright issues,” “Multimodality,” “Electracy,” and “Education.” To the subsection on “Collaboration,” we introduced the work of Catherine Braun and Kenneth Gilbert (2008) to more fully describe processes of academic and interdisciplinary collaboration. In “Copyright issues,” we introduced the scholarship of Danielle DeVoss (2010) which outlines remix strategies for using digital materials in the composition classroom. In “Multimodality,” we made edits to include a conceptual definition of multimodality as inclusive of all communication (Ball and Charlton, 2014). In the subsection on “Electracy,” we added the work of Sarah Arroyo (2013) to extend Gregory Ulmer’s theory of electracy to examinations of participatory culture. Finally, we fleshed out the education section by introducing Elizabeth Clark’s (2010) discussion of ePortfolios, digital stories, online games, Second Life, and blogs as teaching practices. We also added a brief review of a recent multimodal textbook in rhetoric edited by Elizabeth Losh, Jonathan Alexander, Kevin Cannon, and Zander Cannon (2017).

Reflecting on this project’s significance for graduate pedagogy, we especially noticed how it opened up our experience with digital rhetoric and writing beyond conventional coursework. Editing Wikipedia allowed us to move beyond print practices to engage a more public audience and practice digital and pragmatic approaches to rhetoric and communication. As educators, this project also enabled us to begin thinking about how we might interrogate traditional pedagogical strategies and theories, especially in relation to digital technology. We began to think, especially, about the opportunities for other types of active and public pedagogies that this model of education encourages, and how we might enact similar projects in our future classrooms. As an assignment that required public writing, furthermore, this project also enabled us to use Wikipedia as a professional platform for academic writing. Finally, because many of us identify as women, our editorial work in the encyclopedia further helped us to challenge the gender gap by merely expanding its editorial demographic through our participation.

4.3 “Computers and Writing” and Disciplinary Representation

“Computers and writing,” the final article we worked on in this project, was significantly underdeveloped before we began editing and remains somewhat underdeveloped even after our updates. The article’s lack of development also highlighted the arbitrary references used in its creation. There were only two references—one a book by James Gee and Elizabeth Hayes (2011) and the other a link to the website for the academic journal Computers and Composition: An International Journal. It seemed strange that the only reference to academic writing linked to a book on digital literacies (as a field that is certainly relevant but ancillary to computers and writing). This link seemed particularly problematic after researching the history of the subfield and conference because so many of its scholars were absent from the article.

To improve the article’s representation of the many women scholars in the subfield of computers and writing, and to improve the article’s content development, we created a section on the conference’s history, added information about how the field supports minority scholars, and, finally, added a review of the concept “cultural ecology” to better represent theoretical work of women scholars more directly related to the computers and writing community. Creating a section about the history of the conference helps highlight the important work of scholars in this field—many of whom are women—and also allowed the conference and field to be noted for having feminist roots. For this edit, we relied especially on the historical work of Lisa Gerrard (1995; 2006). To better represent the field and conference’s support of minority scholars, we added information about an award presented annually at the Computers and Writing Conference, the Gail Hawisher Caring for the Future Scholarship, as well as how such an initiative supports efforts for inclusion (Butler et al., 2017). A final goal of this editorial work was to add an informative review of the theoretical concept cultural ecology. Drawing from seminal works by Gail Hawisher, Cynthia Selfe, Brittney Moraski, Melissa Pearson (2004), and Kristine Blair (1998), we contributed to the disciplinary representation of female voices in this article while also updating its illustration of major disciplinary theories.

By bringing in scholarly discussions by these women scholars, furthermore, our edits serve as a collaborative effort to help alleviate the gender gap on Wikipedia. We seek to inject diverse voices into the Wikipedia’s coverage of computers and writing. As such, this Wikipedia editing practice, albeit not offering a conclusive solution to problems of representation of women on the digital platform, serves as an initial effort to make Wikipedia a more inclusive space for all scholars.

5. Implications and Opportunities for Graduate Pedagogy

As a form of public and disciplinary engagement, the Wikipedia contributions theorized in this article represent a form of critical digital praxis applied to a public intellectual project. Such praxis, in a Freirean and Arendtian tradition, begins as critical examination and reflection on the encyclopedia as an inherently biased and uneven site for the production of knowledge. Wikipedia’s gender gap, as shown in our citation analysis, emerges even along disciplinary lines, and becomes manifest in specific articles through its omission of non-male scholars. This project sought to remediate this gap through direct editing to include these scholars. Such work materializes the scholarship of women researchers through representation in what has become the defacto encyclopedia and global source of public knowledge, Wikipedia. As part of the coursework in a doctoral seminar in Literacy and Technology, our work on this project also allowed students to engage with research related to course topics (multimodality, digital rhetoric, computers and writing) as they updated and added to Wikipedia articles.

Our decision to attempt a collaborative scholarly article that reports on this project, furthermore, represents a conscious effort to engage in more meaningful coursework that deliberately breaks with traditional academic norms of individual performance and assessment in graduate education. Writing a collaborative scholarly article with multiple authors (10, in this case) presents specific challenges in terms of organization, coherence, and task delegation. It also poses challenges for assessment of individual work. However, engaging students in this type of collaboration ultimately facilitates collaborative writing practice and encourages professional applications of course projects.

This project sought to unpack, analyze, and remediate systems of social oppression in Wikipedia, especially those stemming from and intersecting with the well-documented systemic bias related to the community's gender problems. It also sought to illustrate the embodied multimodality of knowledge production in what has become the encyclopedia of our time. Wikipedia’s representation (or non-representation) of non-male scholars matters because such processes dictate and produce discursive and material realities related to ethos, authority, and academic reputation to a wider public audience outside academia. Our edits, although limited to a handful of articles, work towards broader representation of and materialization of women scholars in fields related to digital rhetoric and computers and writing. Although these acts of public writing were focused on and in Wikipedia, we also hope, through this project, to encourage other scholars and teachers of rhetoric, writing, and digital media to imagine performances of critical digital praxis in new contexts, especially those immediately accessible to our students. What might critical digital praxis look like when applied to other digital communities and interfaces? What might be accomplished through those acts? We conclude by asking our readers to consider those questions.

References

Arendt, H. (1958). The human condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Arroyo, S. (2013). Participatory composition: Video culture, writing and electracy. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Ball, C. & Charlton, C. (2014). All writing is multimodal. In Adler-Kassner, L. & Wardle, E. Naming what we know: Threshold concepts of writing studies (p. 42-43). Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Blair, K. (1998). Literacy, dialogue, and difference in the “electronic contact zone.” Computers and Composition, 15, 317-329.

Braun, C. C & Gilbert, K. L. (2008). This is scholarship. Kairos, 12(3).

Butler, J., Cirio, J., Del Hierro, V., Gonzales, L., Robinson, J., & Haas, A. (2017). Caring for the future: Initiatives for further inclusion in computers and writing. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 22(1).

Ceraso, S. (2014). (Re)Educating the senses: Multimodal listening, bodily learning, and the composition of sonic experiences. College English, 77(2), 102-123.

Clark, J. E. (2010). The digital imperative: Making the case for a 21st-century pedagogy. Computers and Composition: An International Journal for Teachers of Writing, 27, 27-35.

Cohen, N. (2011, January 30). Define gender gap? Look up Wikipedia’s contributor list. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/31/business/media/31link.html?r=3&hp

Collier, B., & Bear, J. (2012, 11-15 February). Conflict, confidence or criticism: An empirical examination of the gender gap in Wikipedia. Paper presented at the CSWC’12 on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Seattle, WA. doi:10.1145/2145204.2145265

Devoss, D. N. (2010). English studies and intellectual property: Copyright, creativity, and the commons. Pedagogy, 10(1), 201-215.

Eyman, D. (2015). Digital rhetoric: Theory, method, practice. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Fotopolou, A., & O’Riordan K. (2014). Introducing queer feminist media praxis. Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, 5.

Freire, P. (2007). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum.

Gee, J. P., & Hayes, E. R. (2011). Language and learning in the digital age. London, U.K.: Routledge.

George, D. (2002). From analysis to design: Visual communication in the teaching of writing. College Composition and Communication, 54(1), 11-39.

Gerrard, L. (1995). The evolution of the computers and writing conference. Computers and Composition. 12, 279-292.

Gerrard, L. (2006). The evolution of the Computers and Writing Conference, the second decade. Computers and Composition, 23, 211-227.

Glott, R., Schmidt, P., & Ghosh, R. (2010). Wikipedia survey - Overview of results. Retrieved from http://www.ris.org/uploadi/editor/1305050082Wikipedia_Overview_15March2010-FINAL.pdf

Gourlay, L. (2010). New approaches to qualitative research: Wisdom and uncertainty (1st ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Taylor & Francis.

Gruwell, L. (2015). Wikipedia’s politics of exclusion: Gender, epistemology, and feminist rhetorical (in)action. Computers and Composition, 37, 117-131. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2015.06.009

Hargittai, E., & Shaw, A. (2014). Mind the skills gap: The role of internet know-how and gender in differentiated contributions to Wikipedia. Information Communication and Society, 18(4) 424-442. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2014.957711

Hawisher, G., Selfe, C., Moraski, B., & Pearson, M. (2004). Becoming literate in the information age: Cultural ecologies and the literacies of technology. College Composition and Communication, 55(4), 642-692.

Joiner, R., Gavin, J., Duffield, J., Brosnan, M., Crook, C., Durndell, A., Lovatt, P. (2005). Gender, internet identification, and internet anxiety: Correlates of internet use. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 8(4), 371-378. doi:10.1089/cpb.2005.8.371

Jones, L. A. (2010). Podcasting and performativity: Multimodal invention in an advanced writing class. Composition Studies, 38(2), 75-91.

Kaur, J., Radicchi, F., & Menczer, F. (2013). Universality of scholarly impact metrics. Journal of Infometrics, 7(4), 924-932.

Losh, E. M., Alexander, J., Cannon, K., & Cannon, Z. (2017). Understanding rhetoric: A graphic guide to writing. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Mills, K. A. (2011). The multiliteracies classroom. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Rohan, L. (2010). Everyday curators: Collecting as literate activity. Composition Studies, 28(1), 53-68.

Selfe, C. L. (2009). The movement of air, the breath of meaning: Aurality in multimodal composing. CCC, 60(4), 616-663.

Shipka, J. (2005). A multimodal task-based framework for composing. College Composition and Communication, 57(2), 277–306.

Shipka, J. (2011). Toward a composition made whole. Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press.

Shipka, J. (2016). Transmodality in/and processes of making: Changing dispositions and practices. College English, 78(3), 250-257.

Vetter, M., McDevitt, T., Weinstein, D., & Sherwood, K. (2017). Critical digital praxis in Wikipedia: The Art+feminism Wikipedia edit-a-thon. Hybrid Pedagogy.

Vetter, M. & Pettiway, K. (2017). Hacking heteronormative logics: Queer feminist media praxis in Wikipedia. Technoculture, 7.

Wadewitz, A. (2013, July 26). Wikipedia’s gender gap and the complicated reality of systemic gender bias (Web log post). Retrieved from https://www.hastac.org/blogs/wadewitz/2013/07/26/wikipedias-gender-gap-and-complicated-reality-systemic-gender-bias

Wikipedia Human Gender Indicator. (2017, November). Gender by language. Retrieved from http://whgi.wmflabs.org/gender-by-language.html

Wikipedia. (2017). Wikipedia: Systemic bias. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Systemic_bias

Wysocki, A. F. (2012). Into between—On composition in mediation. In K. L. Arola & A. F. Wysocki (Eds.) Composing(media) = composing)embodiment) (pp. 1-24). Boulder, CO: Utah State University Press.

Yancey, K. B. (2014). Made not only in words: Composition in a new key. In C. Lutkewitte (Ed.), Multimodal composition: A critical sourcebook (pp. 62-88). Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martins.