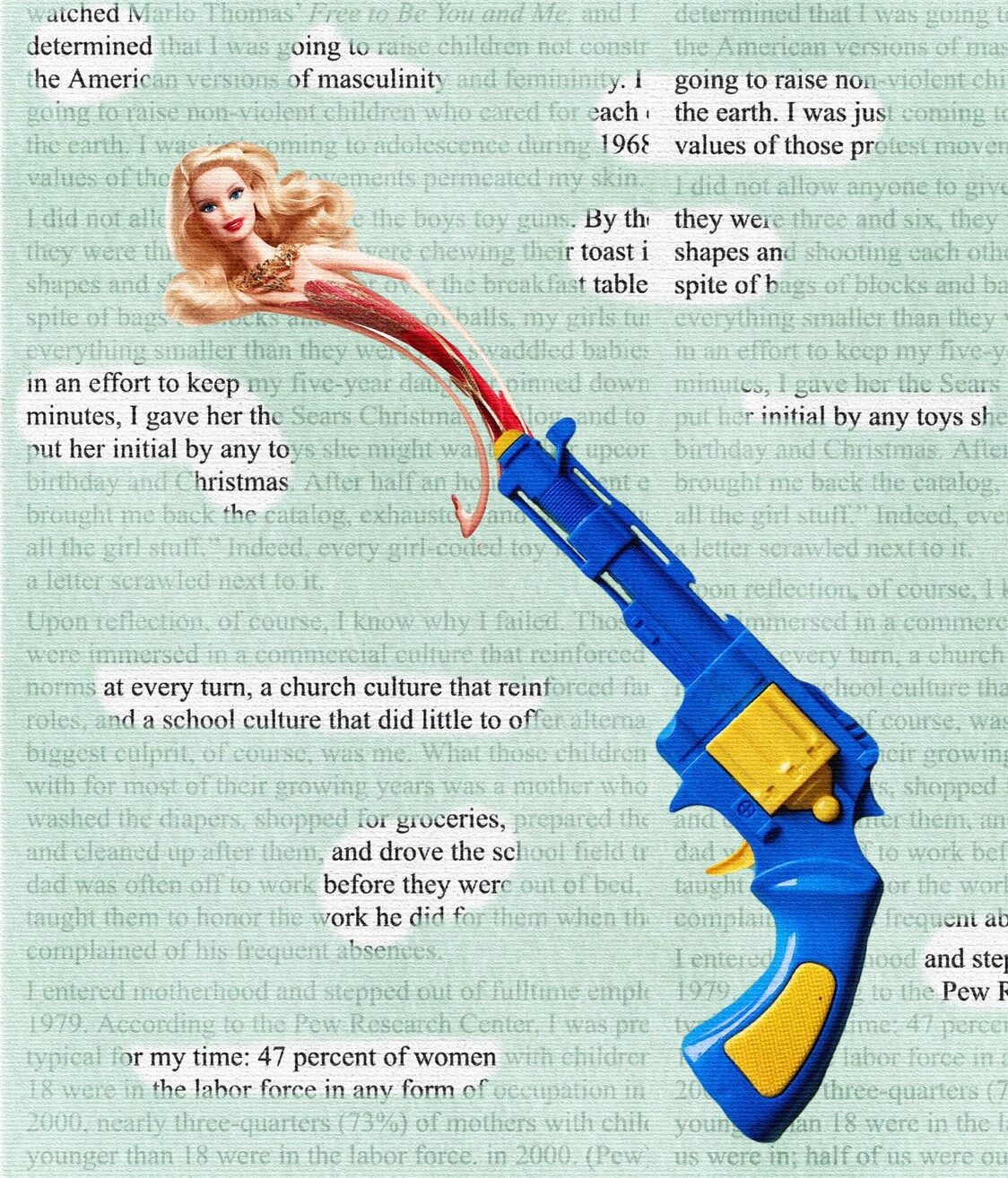

"Engendering Children," image by Ashley Pryor

III.

Aside from some gently used mattresses I cannot even give away because of the fear of bedbugs, a couple of moth eaten braided wool rugs that need to go the dump, a desk, and some cases of canning jars, the bulk of my attic is given over to my children’s toys. As each one left me, they packed up their toys and left them in my care. There are five of those children, so the piles are deep.

When I confront those toys now, I experience a mixture of longing for the children who once loved them, delight in treasures I thought lost, and confoundedness. What am I supposed to do with the Barbie swimming pool and two Corvettes, the model gunship, the scattered pieces of the Polly Pocket castles, the random He-man characters, and the bags of stuffed lions and tigers and bears?

But even as I sort through those emotions, I am confronted by the very gendered-ness of those toys. The toys are clearly encoded girl toys and boy toys. The girl toys are predominantly pink and pastel, the boy toys mostly green, tan, and brown, camouflaged. The girl toys are mostly associated with homes—castles, doll houses, miniature appliances—and child care—baby beds, high chairs, strollers. The boy toys are associated with movement—match box cars, sewer systems, fighting vehicles for land and air—and building things—Legos, dump trucks, hammers and saws.

I read Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique when I was in seventh grade and it helped me name my own sense of something wrong. The eighth-grade boys got to use the gym all fall and through the winter for basketball practice. The girls were relegated to the asphalt playground with rubber balls for foursquare and yellow vinyl jump ropes. The boys got to watch the world series on a TV wheeled into Sister Martin Mary’s classroom, while the girls were supposed to sit in the other room and read. Inspired by a nascent feminism, I circulated a petition demanding equal gym time for girls. It went nowhere. I then used the time we spent loitering on the playground bored by foursquare to write alternative lyrics to Christmas songs. That got me sent home from school. I led a protest march around the gym during music class against the sexist nature of the songs we were rehearsing for eighth-grade graduation—Faith of Our Father and Onward Christian Soldiers. As a consequence, the girls were banned from singing or receiving any prizes during graduation. The boy who won third place in the state speech tournament got a trophy; I had taken first place and got no mention.

I carried that feminist sense with me right into mothering. I watched Marlo Thomas’ Free to Be You and Me, and determined that I was going to raise children not constrained by the American versions of masculinity and femininity. I was also going to raise non-violent children who cared for each other and the earth. I was just coming to adolescence during 1968, but the values of those protest movements permeated my skin.

I did not allow anyone to give the boys toy guns. By the time they were three and six, they were chewing their toast into gun shapes and shooting each other over the breakfast table. And in spite of bags of blocks and baskets of balls, my girls turned everything smaller than they were into swaddled babies. Once, in an effort to keep my five-year daughter pinned down for ten minutes, I gave her the Sears Christmas catalog and told her to put her initial by any toys she might want for her upcoming birthday and Christmas. After half an hour of diligent effort, she brought me back the catalog, exhausted, and said, “I just want all the girl stuff.” Indeed, every girl-coded toy in the catalog had a letter scrawled next to it.

Upon reflection, of course, I know why I failed. Those children were immersed in a commercial culture that reinforced gendered norms at every turn, a church culture that reinforced familial roles, and a school culture that did little to offer alternatives. The biggest culprit, of course, was me. What those children lived with for most of their growing years was a mother who daily washed the diapers, shopped for groceries, prepared the meals and cleaned up after them, and drove for school field trips. Their dad was often off to work before they were out of bed, and I taught them to honor the work he did for them when they complained of his frequent absences.

I entered motherhood and stepped out of fulltime employment in 1979. According to the Pew Research Center, I was pretty typical for my time: 47% of women with children under 18 were in the labor force in any form of occupation in 1975; by 2000, nearly three-quarters (73%) of mothers with children younger than 18 were in the labor force ( Geiger and Parker). Half of us were in; half of us were out. The work I shared with millions of other women was largely invisible, and, I would argue, still is. Sisyphus’ frustrated labor is really just a metaphor for housework. The routine work of keeping food stocked and prepped, clothes clean, permission slips signed, homework reviewed, and floors vacuumed comes undone overnight. The woman who has assumed the work of keeping the family running pushes the same damn rock up the same damn hill day in and day out. Nothing is ever finished, and no prizes are handed around. No one notices. The invisibility of the labor attaches itself to the laborer. The woman becomes as invisible as the work.

The other work I did around them was invisible as well. I worked for many of those years as a free lance journalist, earning Society of Professional Journalist awards and a reasonable share of our family income. The earnings were made even more profitable because I incurred no daycare costs and purchased no household help. I conducted interviews by phone during naptime, and occasionally in person while the children stayed with one of the mothers in the babysitting co-op. Of course, every hour cost me one credit per child, so I often had to repay the pot by watching several children at once. I wrote at 4:30 in the morning while the children were still asleep. I thought everything was going well enough until I found out it wasn’t.

We moved across the country for my husband’s work and to save a marriage that ultimately could not be salvaged. When my children graduated one by one from high school, they left me not just for college, but for their father’s house. I think every mother who has worked so diligently to prepare her children for the day she will not be there feels some sense of abandonment when children embrace their emancipation. But since they left me as they did and left behind the toys I had tended for them—finding the lost Barbie shoe, rescuing the Lego block from the vacuum cleaner, sewing the tail back on the stuffed dog—my sense of abandonment was compounded.

Why I ended up with custody of the toys is a matter of some dispute. Memories are indeed individual and fallible. One son says he only took what he needed and had no place to store the toys. Another says he left them for his little sister. Another had already handed on most of hers by the time she left. And yet another says she’s just not sure. This much is true: all of them were in that liminal space between childhood and adulthood, and none of them had a place to plant the roots that had been uprooted by the divorce. And I suspect that in putting away their toys they were putting away pieces of their childhood as they took the painful first steps into adulthood. The youngest did not leave in the same fashion. Many of her toys ended up in the attic anyway. We moved when she was in sixth grade, and many of those toys, packed in boxes and stowed by the movers, just never made it back downstairs.

Those same children are now raising children of their own. And fortunately, time does heal many things. They have, happily, reclaimed me. This does not mean they have come to claim their left-behind toys. At least not all of them. Part of my desire to clean the attic is to get these abandoned toys back into the hands of their original owners while their children are still children. These chosen few toys might have a second life. But time flies. I mailed one big box to my oldest son when his son was getting old enough to play with Legos. A couple of my daughters, in a second curation, came and selected a few of their collected toys. All of them swear that they are going to come some day and sort through the rest. We live in different cities now, in different regions, and every single one of us is fully occupied.

And so, I sort. And so, I think of what I might mail away, and what I might toss. And as I do, I wonder what a full generation of feminists did right that our daughters are school directors, CEOs, and medical professionals, and our sons are soldiers and scientists. I wonder what we did wrong as my daughters call me in those few spare moments as they leave work for the grocery store before they have to get home to start dinner. What do you think?