Constellating Arts-based and Queer Approaches: Transgenre Composing in/as Writing Studies Pedagogy

Kristin LaFollette, University of Southern Indiana

Abstract

Visual art, when intersected with writing, resists traditional norms in composition and creates space to embrace alternative composing forms and voices, and this project argues for the benefits of intersecting art and writing in the teaching of writing (and I use the term “transgenre” to refer to work that contains both elements of visual art and writing). This research uses arts-based and queer methodologies to explore the benefits of transgenre composing and the ways it challenges composition teachers and students to rethink their composing practices and pedagogical approaches to writing. Traditionally, the alphabetic document has been privileged in academic settings, but arts-based and queer approaches provide lenses through which to (re)examine traditional academic practices so that over-simplified binaries can be broken down. This project also utilizes textual analysis, interviews (from authors who have published transgenre compositions), and collage as methods. In employing these methods and methodologies (and in being a tangible representation of what transgenre composing can look like through the intersection of image and text), this project works to (re)imagine traditional academic norms and advocate for the use of art in writing.

Keywords: Arts-based Research; Arts-based Pedagogy; Queer Theory; Transgenre Composing.

Introduction

Note: This project is designed for the reader to analyze/perceive images as text, so visual art (particularly collage work) is woven into the text. Excepting student examples, all of the artwork in this project is my own work.

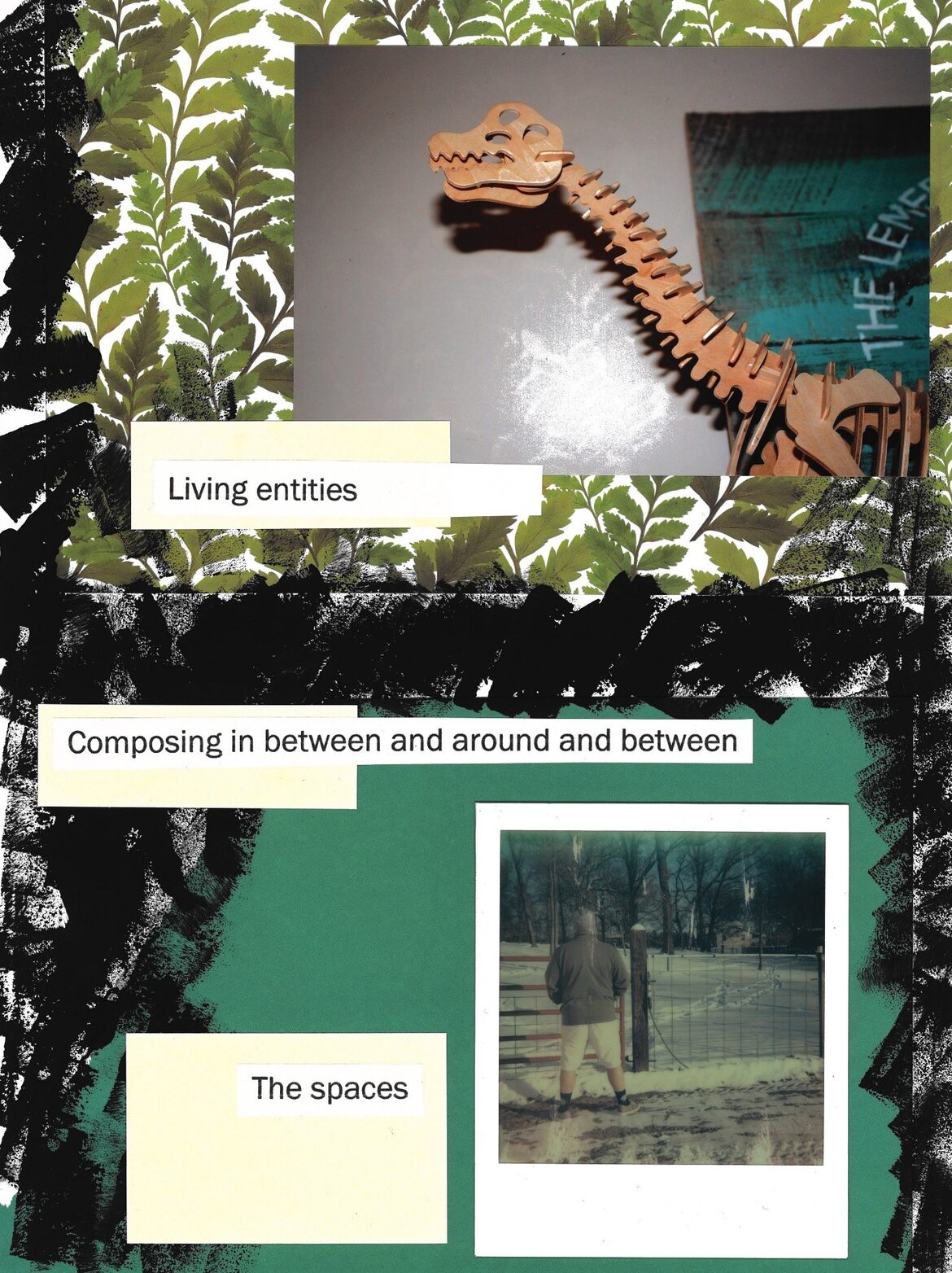

This essay begins with a story. I spent the first three years of my undergraduate career as a pre-med student. In the middle of my third year, I told my academic advisor I wanted to change my major. She asked me what else I liked, and I told her I liked to write. She suggested English and creative writing and I said I would give it a try. The next semester was a trial-run for me, but I enjoyed all my classes and decided to continue on as an English major. During the final semester of my program, I needed to take an upper-level English course to fulfill a humanities elective. I chose a class called “Narrative Collage.” I didn’t know what the class was about going into it, but we ended up discussing the intersections of art and writing (what our professor referred to as “narrative collages”), reading and analyzing works of narrative collage, and creating our own compositions that combined both art and writing. I kept a collage novel throughout the entire class and continued to use it and the art supplies I accumulated during the class even after graduation. Two weeks after finishing my final courses during summer school for my undergraduate degree, I began a master’s program in English and creative writing at the same institution. My concentration was in poetry, but when the time came to assemble a committee and start my thesis project, I talked with the professor who taught the narrative collage course and asked if my thesis could be a narrative collage. She loved the idea but needed to check with the department chair to see if it would meet the requirements for a thesis project in the program. She was concerned that the project would be considered too much “art” and not enough “writing” (see Figure 1). While the project was eventually approved, I had to submit an alphabetic “context essay” that provided background information on the project and discussed other pertinent authors/artists whose work impacted the thesis project. The initial skepticism about my thesis project and the need for a context essay led me to question whether creative work was valued on the same level as traditional scholarly work, especially work that incorporated art. I began wondering: As an “academic,” was my passion for art and writing always going to be unrecognized?

|

|

Figure 1: Composing is too complex for simplistic binaries that claim it’s either this or that (ex. scholarly or creative).

|

As a doctoral student, I began making connections between “multimodal composing” and narrative collage: Both composing forms were “non-typical” in that they didn’t follow the traditionally valued print, alphabetic form. Both forms conveyed messages and engaged with audiences in different ways. Both gave audiences the opportunity to experience “writing” in new and exciting ways. During my doctorate, I came across a multitude of research in writing studies on multimodality and saw my professors and my colleagues advocating for the use of digital tools both in their own work and in their classroom spaces. While I frequently use digital tools in my own work and encourage students to do the same, and while I saw many similarities between multimodal work and the work I was doing at the intersections of art and writing, I still questioned whether there was space for creative work in writing studies and in academia as a whole. This questioning came from the pressure I felt as a rising scholar in the field to produce “scholarship”; while there are people in writing studies making creative work (for example, using multimodal tools), this work is not typically considered “creative,” but is rather for “scholarly” or “academic” purposes.

Early on in my doctoral program, I attended a workshop on arts-based research where the facilitator talked about how beneficial it can be for students to utilize creativity and art in the classroom to grasp difficult concepts and, in my case, learn how to become more effective writers. In that workshop, I started to see more clearly that my background as a creative writer could help me as a writing studies scholar and teacher. My passion for art and writing could be used to help students, and my work at the intersections of art and writing had value. In the introduction to Handbook of Arts-Based Research, Patricia Leavy (2017) writes, “Recent research in neuroscience…indicates that art may have unmatched potential to promote deep engagement, make lasting impressions, and therefore possesses unlimited potential to educate” (p. 3). Art’s “unlimited potential to educate” is what has led to this project, and using arts-based and queer approaches, I argue that art is a valuable tool in the teaching of writing. In performing this research, I developed, taught, and reflected upon a writing course that embraced an arts-based pedagogy. In addition, I also used collage as a research method, interspersing this text with visual art and creating my own transgenre composition in the process. The questions I sought to answer in this research project are as follows:

- How does intersecting art and text challenge dominant norms in writing, and how does it break down traditional expectations of writing?

- How can art be used in the writing classroom to help teach writing? How can art and writing work together to create more effective and rhetorically aware composers?

- What is the process of composing transgenre work like?

Before moving forward, I think it’s important to define my key terms. For years, I used the term “narrative collage” to define work that combined both art and writing, eventually adopting the term “hybrid-genre.” Discussions about this project with creative-critical scholar Ames Hawkins eventually led me to adopt the term “transgenre”; they suggested that “hybrid-genre” perpetuated an either/or dichotomy (implying that composing is either this or that) and that “transgenre” better reflected the complex way that composing happens and compositions come to be. While transgenre can be used to refer to any composition that crosses the boundaries of genre, for the purposes of this project, I use transgenre to specifically refer to compositions that use both elements of art and writing (visual art/imagery and text are both present in the composition). I think it’s important to also note that the “trans” prefix in the term “transgenre” is not an appropriation of the term “transgender.” As mentioned, this project embraces a queer methodology and, because of that, I can see how easy it would be to create connections between the terms as this essay goes back and forth between discussions of “queering,” “queer theory,” and “transgenre.” However, I see “transgenre” as a “transdisciplinary” or “transcendent” concept; transgenre composing is an approach that moves freely across boundaries, borders, disciplines, genres, and expectations. It challenges norms while resisting constraints. In this way, it moves beyond what we think/know about traditional ways/forms of writing.

I also want to differentiate between the terms transgenre and “multimodal.” I specifically used the term “multimodal” in this project to refer to digital compositions that utilize digital tools and modalities (audio, video, digital imagery, blog and social media interfaces, etc.). In short, multimodal is used to refer to digital compositions and transgenre is used to refer to compositions that combine art and writing; however, these transgenre compositions (in their “final,” polished forms) may be digital or non-digital, and may have been created using digital or non-digital means. I acknowledge here that a strict separation between digital and non-digital doesn’t often exist in our contemporary world where digital tools and technologies are so prevalent. Instead, many works that start out as non-digital works of art and writing may end up undergoing remediation in the process of being shared with the world online or through eventual print publication. In addition, while this essay is an enactment of the combination of art and writing I advocate for, it is both digital and non-digital. The words have been typed on these pages using a word processor on a computer. The art was created by hand but was then scanned and added to this document. The student work discussed later was created using both non-digital and digital means. While I often refer to artwork in this essay that is made by hand, I acknowledge that even non-digital work can and so often does become digital at some point in time in order to be remediated, reviewed, or shared with a wider audience.

While creating art is a frequently messy process and can require large physical spaces to move around, Paula Gerstenblatt (2013) notes the benefits of creating art when she writes that “the visual arts can open up dialogue among diverse people, offer new insights and reflection, and provide new ways to critique a subject” (p. 296). While multimodality offers scholars and students important tools, digital composing isn’t the only way to experiment with multiple forms. If a composer wants to incorporate drawings, paintings, or cut-and-pasted scraps into their work, this might not be as feasible or doable with only digital tools. Transgenre composing works toward the same goals of multimodality (to give composers a broader range of tools to convey their message and reach their audience) but can involve a more hands-on approach. As mentioned, art has immense potential to educate, and its abilities to enhance the composing process for students deserves more attention and consideration. While I use the terms “transgenre composing” and “multimodal composing” to mean different things, they both utilize composing tools beyond the alphabetic; further, little scholarship exists in writing studies on transgenre composing, but much has been written about multimodal composing. As such, scholarship surrounding multimodal composing served as a springboard in this project for discussing transgenre composing.

Methodologies and Methods

Arts-Based and Queer Methodologies: A Constellated Approach

Within the subfield of cultural rhetorics, the concept of “constellating” has been used in decolonial approaches inside and outside of academic institutions. To decolonize is to break down existing norms and barriers that have been put in place by the dominant culture and/or society. Western ideals are what created the academy, and to decolonize means to challenge those ideals and work toward creating space for all cultures, all ways of knowing, all ways of meaning-making, and all ways of existing and being in the world. “Constellating” allows for this difficult work of decolonizing and emphasizes relationships, culture, storytelling, and the complex ways knowledges are formed and meaning is made. In “Our Story Begins Here: Constellating Cultural Rhetorics,” Malea Powell et al. write that “the practice of constellating gives us a visual metaphor for those relationships that honor all possible realities” (emphasis original). Powell et al. go on to say that the concept of “intersecting” is a linear one that privileges certain knowledges and marginalizes others, but that constellating allows for “different ways of seeing any single configuration within that constellation, based on positionality and culture.” This idea of decolonizing and constellating connects to the concept of an arts-based, queer pedagogy and transgenre composing. Traditionally, only certain forms of writing have been accepted and valued by the academy. The idea that nothing of value exists outside of this is absurd, but these ideals have persevered over time. Scholars in writing studies have attempted to tackle and dismantle these norms in various ways. One way has involved advocating for multimodal composing and the importance of considering constellations – the unique identities and abilities of students, the numerous modalities available to composers, the development of digital tools and technologies, the teaching approaches of instructors, etc.

In this essay, I emphasize the importance of recognizing and celebrating constellations and argue that the arts-based and queer methodologies discussed here are constellated: they are intertwined, are working together simultaneously, and are inseparable. This constellated approach is present both in this essay and in the arts-based, queer pedagogical approach of using art as a tool to teach writing. If the alphabetic document has been the most valued form of the past, then a composition that constellates art and writing is breaking down barriers about what writing is, what writing looks like, and who can be a writer. Powell et al. write, “A constellation…allows for all the meaning-making practices and their relationships to matter. It allows for multiply-situated subjects to connect to multiple discourses at the same time, as well as for those relationships (among subjects, among discourses, among kinds of connections) to shift and change without holding a subject captive.” The constellated arts-based and queer approach creates space for students with complex backgrounds and experiences to utilize their unique identities and to connect to their knowledges and meaning-making practices (and the knowledges and meaning-making practices of others) in their work. While an arts-based approach recognizes the importance of creative-critical thinking and the uniqueness of composers and audiences, queer theory celebrates identity and non-traditional approaches, and this constellation of methodologies is woven within and throughout this essay (and throughout the pedagogical approach this essay advocates for).

An Arts-Based (and Queer) Methodology

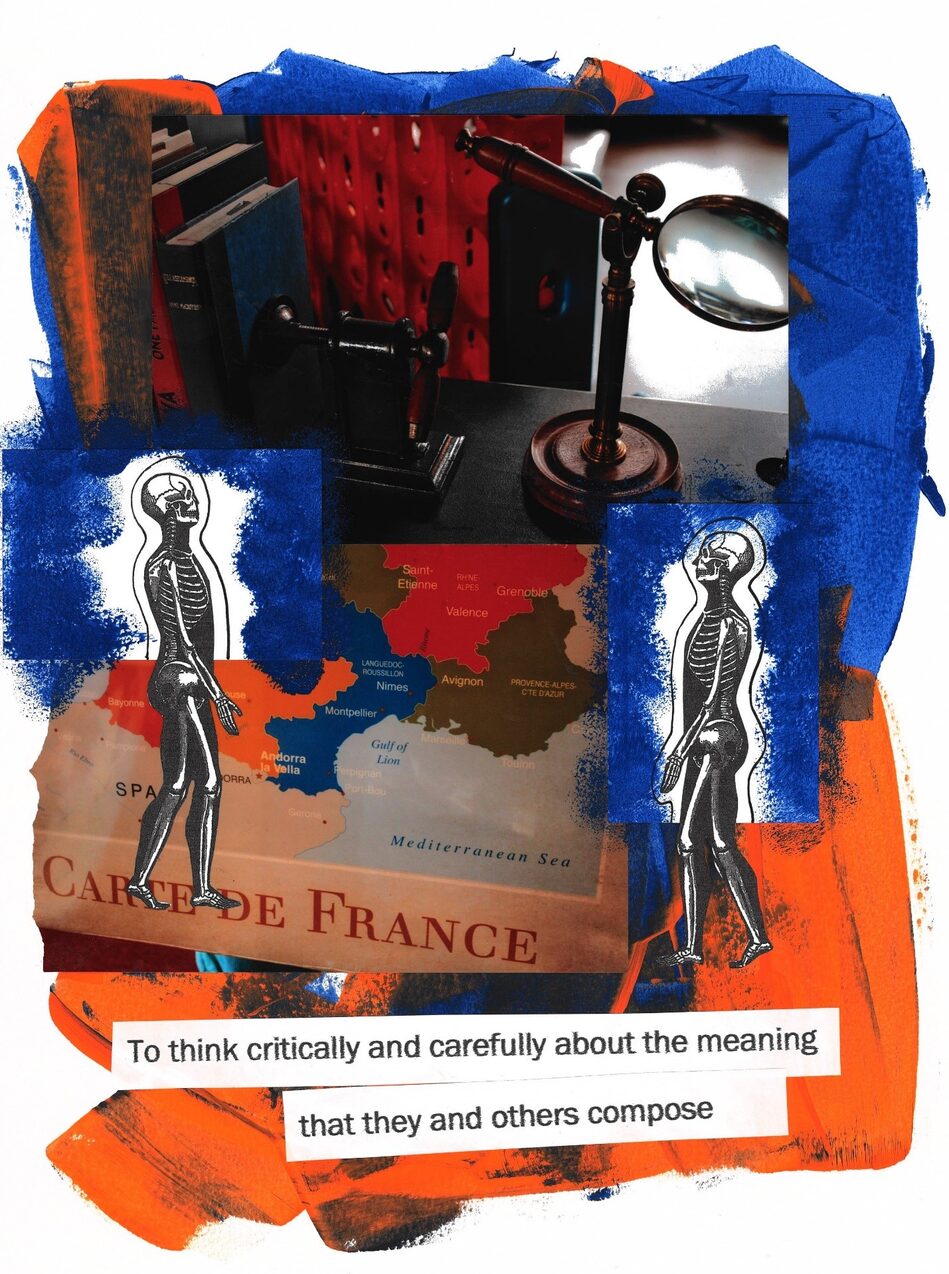

I used an arts-based approach to explore the role art has/can have in composition pedagogy. Art allows people to see and understand concepts in new and different ways, and this is part of what makes an arts-based approach to research so valuable (see Figure 2). In “Arts-Based Methods,” Sandra L. Faulkner and Stormy P. Trotter (2017) note that “arts-based research (ABR) represents diverse qualitative methodologies that rely on an aesthetic process of imagination and artistic expression through various art mediums as a way to understand and examine a research problem, subject, or text” (p. 1). Further, Faulkner and Trotter (2017) state that arts-based approaches involve “the use of art and artistic forms as research represents a holistic methodology that intertwines theory, method, and praxis” (p. 1). My research questions focused on the role transgenre composing can have in shifting traditional ways of teaching composing, and an arts-based approach helped me work toward answering those questions.

|

|

Figure 2: In collage work, the artist assembles an archive of materials and the materials work together to communicate a unique story or message.

|

Specifically, collage is the artistic medium I used in this project. Put simply, I included original collage work throughout so that this project is a representation of what transgenre composing can be/look like and to help me organize and identify important data points (I discuss this in more depth in the paragraphs that follow this one). Collage work, like many forms of art, is a form that works to challenge (or queer) traditional ways of thinking and creating. Dada and Surrealist artists worked to shift what people in the 1910s and 1920s saw as art and shifted who could be viewed as an artist. In Dadaism and Surrealism: A Very Short Introduction, David Hopkins (2004) notes that artists in these movements “were ambivalent...about art as an institution, [and] the Dadaists often pledged to destroy it” (p. 62). Collage helped them work toward that goal as they sought to show that anyone could create collage art with any number of materials. With collage, there isn’t one way of viewing or perceiving. Rather, as Gerstenblatt

(2013) writes, collage “fragments space” and “repurposes objects,” including found materials that wouldn’t normally be considered art, to create a new reality outside the confines of what is traditionally conceived (p. 295). This is a queer notion; the concept of challenging long-held traditions and values about art and artists is woven in and throughout Dada and Surrealist ideals and work (including collage). Certain forms of art were considered superior to others and only certain people could be artists; Dada, Surrealism, and the art of collage queered these ideas and shifted the focus of the art world.

I specifically decided to use collage as opposed to another art form as a method for performing this research for a few reasons. One reason is that transgenre composing developed from Dada and Surrealism, and many of the artists in those movements were creating collage art. Further, since this project argues for the use of art in writing, the collages act as a manifestation of that argument and what the intersections of art and writing can look like. Another reason is that collages are mixed-media and can involve numerous materials, and I think this artistic freedom lends itself to better communicating the goals of this project, which are to advocate for the use of art in the teaching of writing. Further, collage art has the potential to make composition students more comfortable with creating art. It can be intimidating for students who don’t consider themselves “artists” to create art, but collage can be a more approachable way to have students intersect art and writing in their work because they have the option to use already-existing materials (like magazine and newspaper clippings, photographs, etc.).

Collaging also helped me analyze the data I gathered while researching this project. Before starting the collages, I pulled words and phrases from the data I was gathering that “stuck out.” I printed the phrases I selected, cut them out, and laid them all out on my desk. I asked myself:

- How are these pieces of data furthering my project?

- How are they helping me better understand creative-critical work and intersecting art and writing in pedagogy?

In response to these questions, I created collages to accompany the data I pulled from the project, and each of the selected pieces of data was used as the focus for one collage. The resulting collages represented, for me, what I was learning from the data and were a visual representation of the data. The collages also give readers a moment to pause, look at the artwork, and reflect on the important data it represents (and what the artwork/data means to them). The visual elements of each collage don’t merely illustrate the textual elements of the collage, but rather work toward queering readers’ perceptions of the data, following the tenets of Dada and Surrealism.

A Queer (and Arts-Based) Methodology

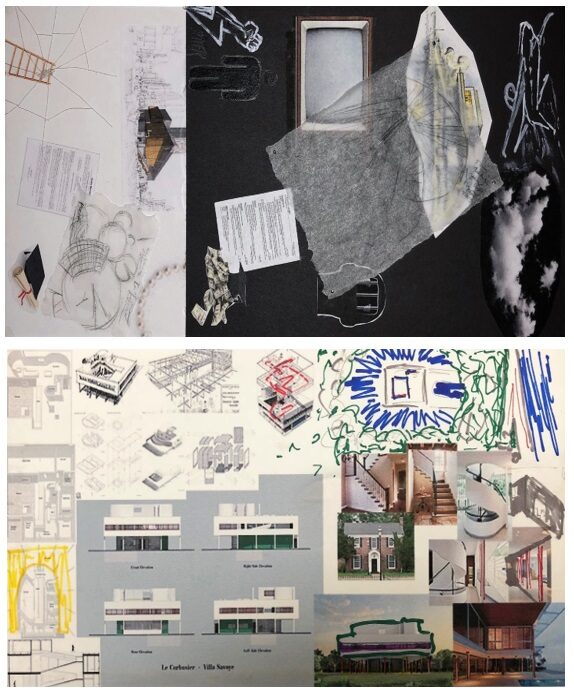

In developing (and constellating) a queer methodology, I’ve built upon scholar Meg-John Barker’s (2016) definition of queer theory: “Queer theory is a theoretical approach that goes beyond queer studies to question the categories and assumptions on which current popular and academic understandings are based” (p. 15). (I want to make clear, however, that while this definition doesn’t directly make the connection, queer theory is inseparable from LGBTQ studies; I make note here of queer theory’s beginnings in LGBTQ studies to acknowledge and appreciate the history of queer theory as a critical lens and methodology). While, as Barker (2016) notes, “queer” describes sexualities, relationships, and gender identities beyond heteronormative traditions, this definition has been expanded to a contemporary theoretical definition that encompasses anything that challenges dominant norms. In examining transgenre work as a queered composing form, I explored the ways it challenges traditional and dominant norms in the teaching of writing (see Figure 3). To use an arts-based approach, to embrace transgenre composing, is queer; to queer is to challenge the status quo, and arts-based approaches in writing classrooms, much like Dada and Surrealist work, attempt to do just that. In “Engaging Queerness and Contact Zones, Reimagining Writing Difference,” Martha Marinara (2012) writes,

At many different moments, queerness erupts to trouble normalcy, legitimacy and signification. Queerness skews, bends, or queers the realities we construct around ourselves...It isn’t only the heteronormative that needs to be bent; all of our centers of status quo stability...need to be refracted, redirected in their transparency to a burst of their colorful parts...In other words, queerness ruffles or disturbs the boundaries and borders of knowledge and practice already in place in the academy. (p. 200)

As Marinara notes, queer theory disrupts long-held traditions and beliefs and challenges people to think critically about constructs. When we queer things (when we see a “burst of colorful parts” rather than the stable object/concept we saw before), we start thinking, seeing, and exploring differently (and the creation of art helps us to queer what we think we know—that writing is “words on a page”—and create/see that “burst of colorful parts”). The alphabetic, print document has been the traditionally valued composing form; intersecting art with writing (in the many forms it can take, both digital and non-digital) breaks through the boundaries of what composing has been in the past and shows what it can be. As such, a queer theory methodology consistently informed this research as I examined the ways that transgenre composing challenges traditional norms in writing studies pedagogy, and this project itself is an enactment of that queer methodology through the constellation of text (writing) and image (art).

|

|

Figure 3: To queer or “misperform” writing is to create something unconventional, to alter assumptions about the forms writing can take. |

A Framework for Transgenre Composing in/as Writing Studies Pedagogy

Art, Multimodality, and Identity

In Jody Shipka’s (2011) Toward a Composition Made Whole, she writes about making students aware of the alternative composing methods available to them. As mentioned, transgenre composing developed out of the Dada and Surrealist art movements, which employed any materials necessary to communicate the goal/purpose of the art. While Surrealist artist Marcel Duchamp’s famous “sculpture” Fountain was nothing more than a urinal, it “needed the arrogance of the art world context in order to be read as art, [and] its readability as art sought to debunk the arrogance on which it thrived” (Bradley, 1997, p. 14). By using a urinal and calling the work Fountain, the object was given much more prestige than a urinal; Duchamp understood that, in order for the piece to communicate what he wanted it to, he needed to use a material that would achieve that goal. Shipka (2011) similarly talks about this awareness and notes that

what makes this framework for composing unique is the responsibility it places on students to determine the purposes of their work and how best to achieve them…A mediated activity-based multimodal framework for composing provides metacommunicative awareness without predetermining for students the specific genres, media, and audiences with which they will work. (p. 87)

Duchamp understood the purpose of Fountain and created the art accordingly; transgenre composing gives students the opportunity to do the same thing and become more effective and aware composers in the process.

Proponents of multimodal composing have argued for years that students benefit when they are given the opportunity to use the composing form that best fits their needs and message. In “The Movement of Air, the Breath of Meaning: Aurality and Multimodal Composing,” Cynthia Selfe (2009) argues that the field of writing studies’ history of valuing the print document over other composing methods has worked to limit “our professional understanding of composing as a multimodal rhetorical activity and [has deprived] students of valuable semiotic resources for meaning making” (p. 617). Transgenre composing works toward breaking down these outdated expectations in writing studies; a prime example of this is the “ballet shoes” example Shipka (2011) discusses in the introduction to Toward a Composition Made Whole. A student wrote her essay on a pair of ballet shoes and, when Shipka was facilitating a workshop on multimodal composing and mentioned this particular student project, workshop attendees expressed skepticism about the project’s “scholarly” nature. However, Shipka (2011) noted, “I was positioned…in ways that allowed me to see, and so to understand, the final product in relation to the complex and highly rigorous decision-making processes the student employed while producing this text” (p. 3). Here, Shipka focused on a remixing of the traditional where process and rhetorical decision-making are just as valuable as the final product. Creating art is a hands-on process and involves making rhetorical decisions about the use of certain materials, the placement of certain pieces/parts, etc., and we know that writing is also a deeply rhetorical process. Including both art and writing together not only works toward this process-focused approach of teaching writing, but also gives students the opportunity to create and write about things that are important to them.

This essay focuses on a constellation of arts-based and queer approaches, and expression and identity are both at the forefront of these approaches. In Experimental Writing in Composition: Aesthetics and Pedagogies, Patricia Sullivan (2012) writes about how alternative composing forms create space for identity, individuality, and artistic freedom:

Though the lines dividing different pedagogical projects can be blurry and shifting, in general these arguments claim that through the ‘freer’ aesthetic space created by experimental and alternative discourses, students may be allowed to express their unique individualities, articulate marginal or underrepresented social realities, and/or critique the limits of dominant sociopolitical discourses and the institutions that perpetuate these discourses. (p. 2)

This statement reflects an arts-based and queer focus which works to destabilize the prescribed norms that have pervaded academic institutions and, specifically, composition classrooms for years. There are forms and ways of composing that have traditionally been valued over others, and transgenre composing provides a way for students to work around those prescribed norms and create new realities through freedom of expression (see Figure 4).

|

|

Figure 4: Transgenre composing allows students to embrace their interests and identities and experience freedom of expression.

|

Art as a Tool for Teaching Queer

In Stacey Waite’s (2017) Teaching Queer: Radical Possibilities for Writing and Knowing, she talks about several patterns in scholarship on queer pedagogy, including that these discussions are typically specific to LGBTQ subjects (students and/or teachers who are queer), that queer teaching is limited to the reading of LGBTQ texts, and that discussions of student writing seem to be focused on how to respond to homophobic writing or how to teach students to celebrate diversity in writing (p. 5). Waite (2017) writes that she values these discussions and considers them in her own teaching; however, in her book, she examines the intersections of queer theory, writing, and pedagogy and how they “move into one another” (p. 5). She writes, “I want to consider queer possibilities for the teaching of writing with particular attention to college writing courses. I want to continually develop queer methodologies, thinking of queer pedagogies as sets of theorized practices that any student or teacher might engage” (Waite, 2017, p. 5). Similar to what Waite notes here, I think of queer pedagogical approaches as being for all instructors and all students in writing classrooms. Waite (2017) goes on to say,

I offer writing and teaching as already queer practices, and I contend that if we honor the overlaps between queer theory and composition, we encounter complex and evolving possibilities for teaching writing. I argue for and employ what I call ‘queer forms’—nonnormative and category-resistant forms of writing that move between the critical and the creative, the theoretical and the practical, the rhetorical and the poetic, the queer and the often invisible normative functions of classrooms. (p. 6)

In my writing courses (and in the intermediate writing course/case study I will discuss in a moment), these “queer forms” come through via transgenre composing; students are learning about and practicing writing, but are weaving that writing into creative, practical, and poetic forms, to use Waite’s terms.

In Teaching Queer, Waite (2017) also argues that the individual components of our identities cannot be separated from each other and that a queer pedagogy involves intersecting theory, story, and identity (and I utilize this same intersecting—or constellating—in this essay). Like the arts-based pedagogical approach I discussed in the previous subsection, a queer approach similarly creates space for identity and writers’ unique forms of expression. Waite (2017) claims that narrative is just as important as theory and that stories are knowledge (emphasizing the importance of constellations and constellating), much in the same way art and writing can work together to create new ways of thinking and telling a story. Waite (2017) writes,

I want to offer a particularly queer understanding of what narrative might mean to theory and, dialectically, what theory might mean to narrative. I most closely link my own understanding of the scholarly use of narrative to Nancy K. Miller’s understanding in Getting Personal: Feminist Occasions and Other Autobiographical Acts. She writes, "…By turning its authorial voice into spectacle, personal writing theorizes the stakes of its own performance…Personal writing opens an inquiry on the cost of writing—critical writing or Theory—and its effects." (p. 15)

Waite’s idea of queer pedagogy involves the personal and the narrative as “spectacle,” or making public what is usually left private. In understanding, discussing, and interacting with one’s selfhood and embodied subjectivities, a queer pedagogy can be enacted in the teaching of writing. Art not only allows students to choose the form that best fits their project, goals, and the needs of their audience, but it creates opportunities for self-expression.

This concept of identity as a central tenant of queer theory and a queer pedagogy is furthered in Hawkins et al.’s “Courting the Peculiar: The Ever-Changing Queerness of Creative Nonfiction.” In the essay, Barrie Jean Borich (2014) stated,

As a teacher to have no center means to me, in part, that there is no one canon, no one mandatory reading list, no center bar to which we are all to aspire. This means when I teach I focus on authorial intention, within a world view where the author and the world the author speaks from is their own, while still attempting to embrace all the ways one writer’s center may not be another’s.

Here, Borich talks about her own pedagogy, the decentralized nature of it, and how it accounts for identity. Instead of there being one “truth,” “level” to work toward, or dominant reading list, her queered teaching creates space for all writers and voices. This is a queer concept as classroom spaces have traditionally labeled the instructor the as “expert” and students as the “novices”; in a traditional system, the instructor is the holder of knowledge or “truth,” and they transfer this knowledge to their students over the course of a semester, frequently testing students’ abilities to understand and retain that knowledge with tests and assignments. However, in Borich’s teaching approach, a queering takes place where the instructor and the students act as mutual teachers and learners and individual identity is not only considered but valued (her classes are encouraged to “embrace all the ways one writer’s center may not be another’s”). Transgenre composing (a constellated arts-based and queer approach) works to achieve these goals through providing clear opportunities for self-expression and rhetorical thinking and decision-making. It gives students more ownership over their work, allows them to include their voices and identities at the forefront of their work, and recognizes that one student’s approach may be different than another’s (see Figure 5).

|

|

Figure 5: Queered compositions exist outside of traditional understandings of genre.

|

The Case Study: Transgenre Composition in Intermediate Writing

The Queer Art of Writing

During the Spring 2018 semester at Bowling Green State University, I had the opportunity to design and teach a writing course that encouraged students to create transgenre work; here, I discuss the rationale for that course, explain the transgenre assignments and how some students approached them, and reflect on teaching the course and how the course impacted how I embrace transgenre composing as a teaching tool and a key aspect of my pedagogy. The course I designed was titled ENG 2070 Intermediate Writing, and I subtitled the course Understanding Identity and Queer Theory in Academic Communities. To sum up the course, we focused on queer theory as a lens for thinking critically and writing about identity, normative and traditional constructs and ideologies, and what it means to be a part of an academic community, and we did this through transgenre composing. The goal of the course was for students to learn to write well in their discipline while also exploring the shift from the normative to the non-normative through a queering of traditional academic and writing practices. The course encouraged students to explore the ways composing has been and can be remixed with the use of various digital and non-digital tools and modalities and that choosing a composing form is a very specific rhetorical choice. The traditional alphabetic isn’t the only way to compose, and helping students understand the variety of tools available to them in the course helped them better articulate the rhetorical decisions they made in their compositions, both within and outside their discipline (see Figure 6). The full syllabus/schedule from the course can be found in Appendix A.

|

|

Figure 6: Composers should have the ability to choose the form that best fits the meaning they wish to convey.

|

The course description on the syllabus stated that the class would focus on “remixing (or reimagining) long-standing divisions, dichotomies, and categories” and that students would examine “how queer theory is a lens for seeing how texts cross boundaries and how we can critique those boundaries.” While developing the course curriculum, I saw “remixing” as a queer practice that would help the class understand and embrace non-traditional composing tools and methods (like intersecting art and writing), not just for the sake of being different, but because the particular projects called for a queering of the traditional. This remixing would require students to think in new and exciting ways (which didn’t turn out to always be a comfortable process for them).

Since queer theory gives us the opportunity to examine our own identities and the ways we think, create, learn, and communicate, I wanted students in the course to consider the following in reference to their composing practices:

- Do you compose using only the alphabetic because it’s easy, or because it serves your project well?

- If you are hesitant to embrace new composing forms, why?

- How can queer theory help you be a better scholar and future employee in your field? How can it impact and benefit your composing practices?

The readings and assignments in the course (refer to Appendix A) attempted to help students develop a fuller understanding of the genres of writing that take place inside and outside of their discipline and how to best communicate to their audience. There were five assignments students completed over the course of the semester, and while each assignment helped students build their writing skills and gain knowledge about their disciplines, the assignments themselves remixed long-standing traditions in academic writing in that they incorporated opportunities for alternative composing forms (including multimodal composing—using programs like VoiceThread, Piktochart, and Prezi—and art-making—through methods like collaging, drawing, and painting). I chose to integrate transgenre and multimodal composing into the course to give students many more elements and tools to work with; in doing this, I hoped students would explore and learn more about making sound rhetorical choices and reflecting on how those choices benefit their projects and their audience(s).

Transgenre Student Projects from the Course

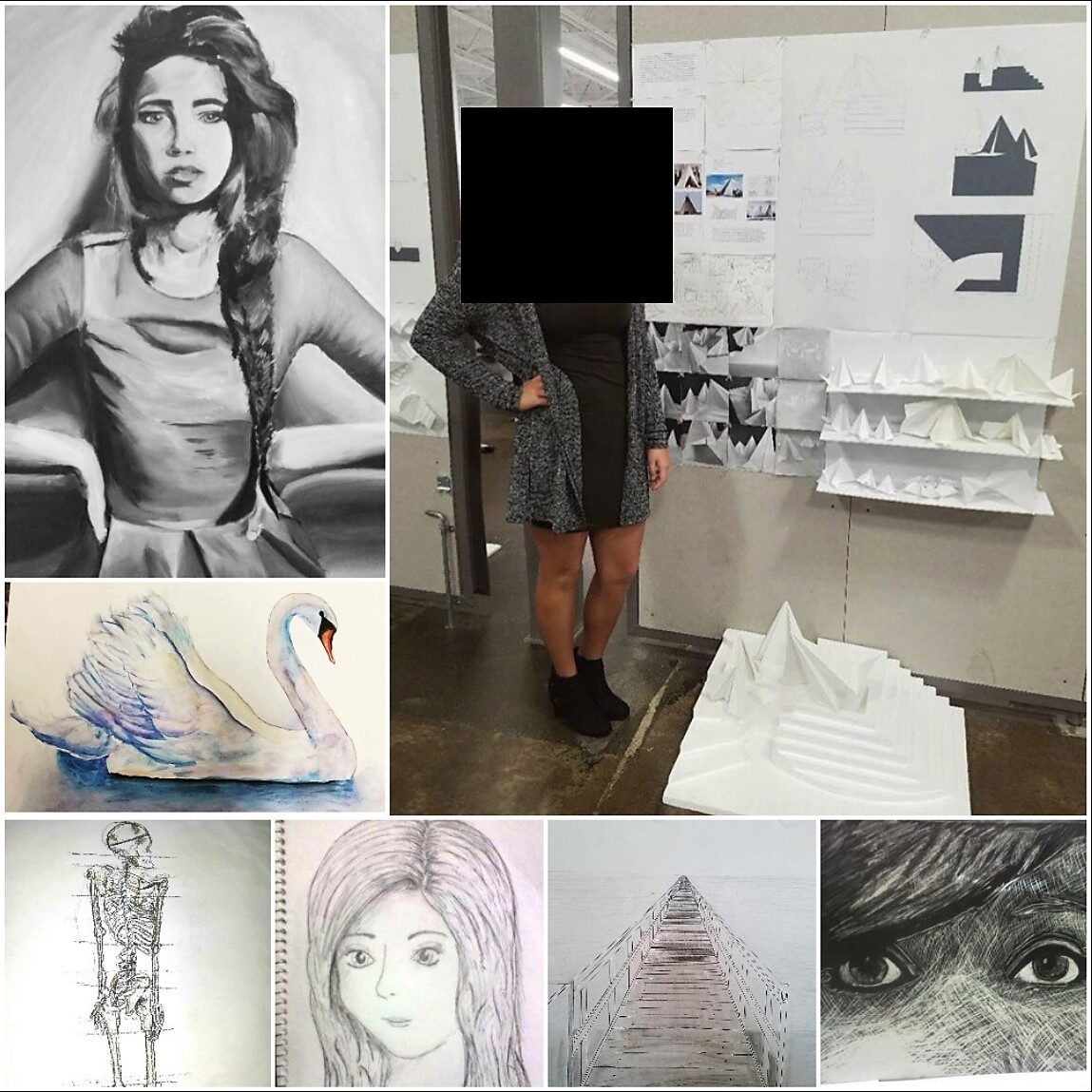

Here, I focus on a few examples of the artwork students created in the course to accompany the written portion(s) of their assignments. Figure 7 features two collages by the same student, whom I will refer to as Jane; the first collage is a depiction of an interview the student did with a faculty member on campus (Project #1), and the second collage was a visual explanation of a conversation Jane explored about architecture in a public forum (Project #2). As Sullivan (2012) notes, normative forms of composing have been critiqued by writing studies scholars “by invoking the liberating and critical power of art” (p. 2). Further, as Sullivan (2012) states, collage also works toward the Surrealist ideals of “breaking away from traditional codes of mimesis and the aesthetics of coherence, and exploring the language of the irrational and the chance encounter’” (p. 109). When creating art and, specifically, collages, students create work that is new, exciting, and entirely theirs. Jane’s collage work is a great combination of experimentation with form/materials and her identity as an architecture scholar, and reading her written work while referring to her visual(s) created an altogether new reading/viewing experience.

|

|

Figure 7: Jane's collages.

|

Figure 8 is a collage that a student, whom I will refer to as Kayla, created to accompany her essay recalling the path that led her to study architecture (Project #4). Kayla’s collage is unique in that it combines several of her own pieces of artwork, including multiple drawings and a photograph of her posing with one of her architecture projects. This collage was completed as part of Project #4, which asked students to use transgenre composing to convey their journey to their chosen discipline. Kayla’s collage tells this story through her own sketches and she noted in her essay how much her love of art and drawing contributed to her pursuing a degree in architecture. Her collage showcased that artwork and, through the artwork and writing, she told a more complete story of her path to becoming an architect (a story that would not have been as engaging or intriguing with text alone). The artwork brings the reader-viewer into the narrative and better communicates her message.

|

|

Figure 8: Kayla's collage.

|

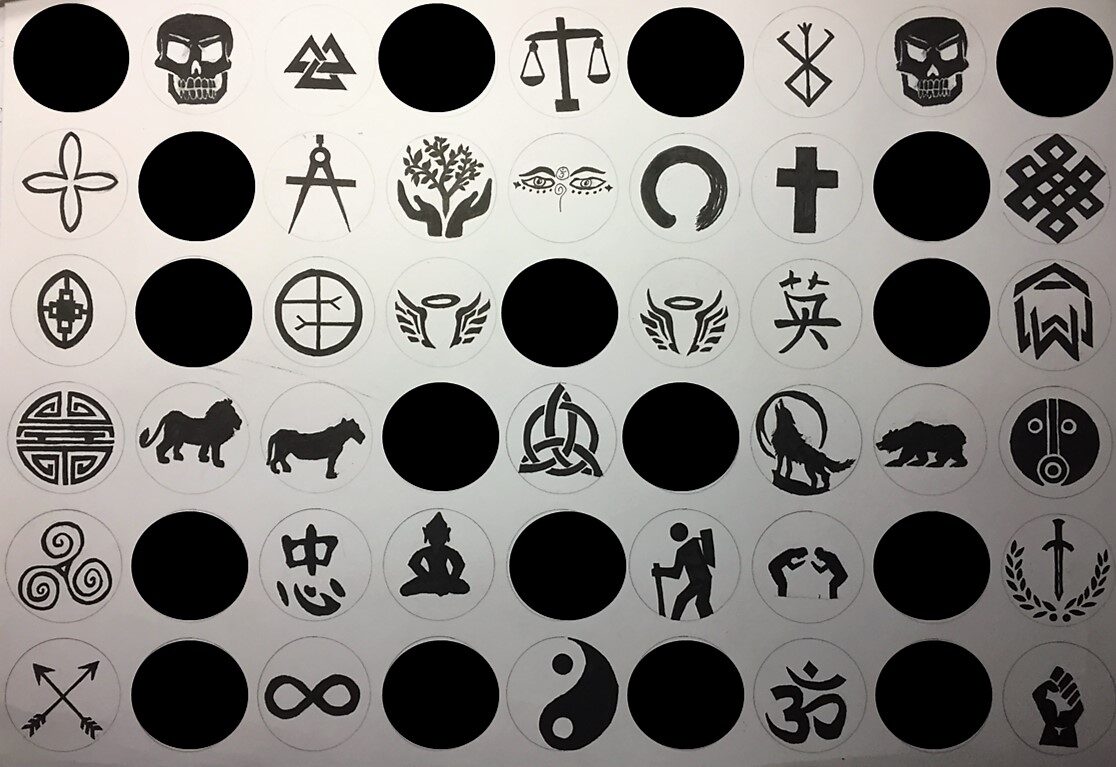

Figure 9 is a piece of artwork that explains the multiple facets of this student’s (whom I will refer to as John) personal and professional identities (Project #4). John (also an architecture student) used his drawing and sketching talents to create the artistic component of his transgenre Project #4. During a conference after the project was complete, he informed me that his ink drawing took him over ten hours to complete. While the Project #4 assignment called for students to discuss/illustrate the path that brought them to their academic fields (and where they saw themselves in a future career), John queered the assignment a bit. He said his love of art certainly contributed to him pursuing an architecture degree, but that there was so much more to his identity as a person and a professional that he wanted to convey through the project. He decided to create this drawing, which is made up of small circles with different symbols in each one; for John, these symbols show who he is as a person and the multiple identities he inhabits on and off campus. The symbols show his spirituality, his love of nature and hiking, his interest in architecture, and more. John very specifically chose to do an ink drawing as opposed to other art forms because he thought it best helped to illustrate his essay, his story, and his identity. Further, as I was reading his essay, the art worked together with the narrative to give me a fuller picture of who John is as a person. John shared a draft of his drawing with the class during workshop/peer review time and many other students were inspired by his drawing and wanted to create a more “artistic” component for their own projects. He was proud of his work, and he enjoyed the opportunity to utilize his skills and talents as an artist. His creativity was contagious, as well, and once other students saw the various forms the art could take, they were more open to trying it themselves.

|

|

Figure 9: John’s drawing (the student’s name was spelled out in the circles, so those circles have been blacked out).

|

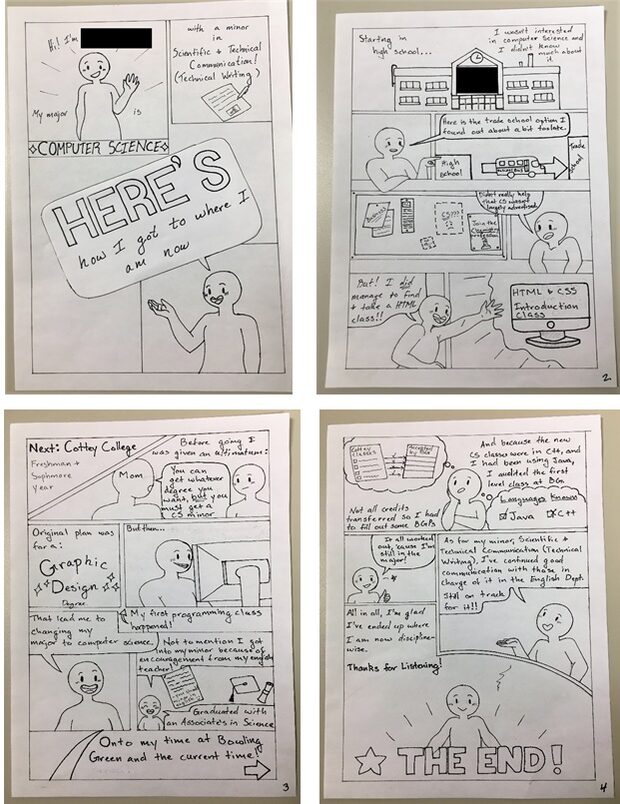

Finally, Figure 10 is a comic strip that illustrates how this student, whom I will call Mary, became a computer science student (Project #4). After introducing Project #4 and brainstorming with Mary in my office, she said the best way for her to tell the story of how she became a computer science major was through a comic strip. Mary described herself as a non-artist, but said she enjoyed sketching and doodling from time to time. Her comic is wonderfully drawn and does a great job of narrating the story of how she came to study computer science. While her essay component was well-written, the combination of image and text in the comic told a better story than the alphabetic alone ever could, and Jason Helms (2017) talks about this unique storytelling experience created by comics in Rhizcomics: Rhetoric, Technology, and New Media Composition. Helms (2017) writes, “Text may call to mind words only, but I am indicating the woven nature of [comics], distinct modes overlapping in a unique composition but also the various other texts (discursive and nondiscursive) to which this thing responds.” While Mary said she was anxious about her drawing skills and creating a comic, she stepped out of her comfort zone and created a transgenre composition. Her project was a wonderful representation of what I was attempting to teach students by encouraging them to intersect art and writing: to become aware of the various composing methods available to them to communicate, and to use the method(s) best suited for their projects to create unique, multifaceted, and interesting compositions.

|

|

Figure 10: Mary’s comic strip (with some identifying information blacked out).

|

In past courses I’ve taught, students were usually more open to digital composing than they were to art-making. They often felt like they didn’t possess enough artistic skill to create a “good” or “interesting” piece of art for their assignment. However, the student population in the ENG 2070 course I describe here was about 50% architecture students. Art is already so much a part of what architecture students do, so many of them excitedly brought their artistic skills into our class for several of their assignments. The results were stunning, and the artwork greatly improved their projects. In addition, the students reported enjoying the assignments more, were proud of their work, and frequently shared the work with the class. When I asked for permission to include the student artwork in this essay, they all enthusiastically agreed. While Jane and Kayla were excited from the beginning about the artistic components of the projects, John and Mary were initially unsure (but they were open to it). When I conferenced with John and Mary and they had the opportunity to map out their projects with me and brainstorm the possibilities, creating art became an approachable and exciting prospect for them, and their art and overall projects reflect that. I also modeled art-making for them, brought in examples of my own artwork, and allowed students to ask questions about my rhetorical decision-making processes.

Ultimately, the students’ transgenre projects were a wonderful showcase of creativity, artistic skills, and the ability to “think outside the box” in a college composition course. I saw firsthand how transgenre composing encouraged them to approach their assignments in new ways, and the art-making gave them excellent opportunities to describe their composing process(es) to me. When prompted, they were able to clearly articulate why they chose the art form they did, why they chose specific materials/colors/ arrangements, and how they were working to better engage their audience with both the art and the writing. Further, they were able to talk about the ways they saw the art and writing working together to facilitate “free thinking.”

Creating, Reading, and Viewing Transgenre Work: A Heuristic

At this point, it’s important to provide a heuristic for how you can think about, consider, and “read” transgenre compositions (including this one). In order to enact an effective pedagogical approach, students should consistently be reminded of why they are doing this work and how they should read/experience their own transgenre compositions and the transgenre compositions of others. How can we teach students to “read” transgenre compositions and fully engage with them so they know how to approach/create them?

- Reading/viewing transgenre work: Read/view the individual aspects of the transgenre composition several times. Try “reading” the composition from left to right, right to left, top to bottom, and bottom to top. How did your understanding/perception of the composition change/evolve/expand when reading/viewing the composition from all directions?

- Creating transgenre work: Think about your goals as a writer and an artist. How might you constellate words and images to challenge (or queer) your reader-viewer’s perception of the composition? How might you use unlikely pairings of text and image to work toward the overall goal of your composition?

- Reading/viewing and creating transgenre work: Helms (2017) writes that scholar Marshall McLuhan (“the medium is the message”) saw the truly participatory nature of “reading” comics and that the “reader is forced to interact with the comic more consciously than with a traditional text.” As such, carefully consider the individual aspects of the composition you are reading/viewing or creating, then think about the ways those individual aspects work together to create the whole. Why did the writer/artist (or you as the writer/artist) choose that layout or those specific colors, images, and/or words? The images and words necessarily work together and aren’t separate entities. How does this impact your perception of a composition or the way you approach creating a transgenre composition? Just like Dada and Surrealist work, transgenre compositions encourage reader-viewers to “think outside the box.” It’s okay to feel uncomfortable or not understand what you are reading/seeing at first and, as a writer/artist, it’s okay to feel challenged by the concept of creating something new and different.

Above all, transgenre compositions embrace the messiness of composition; give students the space to be truly creative, and encourage them to take risks.

Appendix A: Materials from ENG 2070 Intermediate Writing Course

References

Barker, M.J., & Scheele, J. (2016). Queer: A graphic history. Icon Books.

Bradley, F. (1997). Surrealism. Cambridge University Press.

Faulkner, S.L. and Trotter, S.P. (2017). Arts‐based methods. In J. Matthes, C.S. Davis, & R.F. Potter(Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. DOI:10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0009

Gerstenblatt, P. (2013). Collage portraits as a method of analysis in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 12, 294-309.

Hawkins, A., Borich, B.J., Bradford, K., & Cappello, M. (2014). Courting the peculiar: The ever-changing queerness of creative nonfiction. Slag Glass City, 1. Retrieved from http://www.slagglasscity.org/essaymemoirlyric/textual/courting-peculiar-ever-changing-queerness-creative-nonfiction/

Helms, J. (2017). Rhizcomics: Rhetoric, technology, and new media composition. University of Michigan Press.

Hopkins, D. (2004). Dadaism and surrealism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Leavy, P. (2017). Introduction to arts-based research. In P. Leavy (Ed.), Handbook of arts-based research (pp. 3-21). Guilford Press.

Marinara, M. (2012). Engaging queerness and contact zones, reimagining writing difference. Writing Program Administration: Journal of the Council of Writing Program Administrators, 36(1), 200-204.

Powell, M., Levy, D., Riley-Mukavetz, A., Brooks-Gillies, M., Novotny, M., & Fisch-Ferguson, J. (2014). Our story begins here: Constellating cultural rhetorics. Enculturation, 25. http://enculturation.net/our-story-begins-here

Selfe, C.L. (2009). The movement of air, the breath of meaning: Aurality and multimodal composing. College Composition and Communication, 60(4), 616-663.

Shipka, J. (2011). Toward a composition made whole. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Sullivan, P. (2012). Experimental writing in composition: Aesthetics and pedagogies. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Waite, S. (2017). Teaching queer: Radical possibilities for writing and knowing. University of Pittsburgh Press.