Strolling Facebook: The #Rural Facebook Flânuer Seeks and Shares Beauty in the Ugliness of COVID

Jen Almjeld, James Madison University

In the early days of the Covid-19 lockdown, I spent lots of time on Facebook. Much more time than usual. Like so many others, I went to the space seeking information on the pandemic and the lockdown, updates from friends and family, distraction, and also ways to act locally to help others. I also, surprisingly, found inspiration to leave my computer — and my home — and to seek escape and solace in the natural world via daily 3-, 4- and sometimes 5-mile walks. What I find extraordinary now — some two years later — was not my desire to connect with and be in the outdoors, but instead my need to photograph and then document those seemingly unplugged moments for others on Facebook and other social media sites like Instagram. Why did I feel so compelled and comforted by bringing the natural world to my computer, particularly during the dark lockdown days? While it is tempting to consider ourselves post-pandemic, new variants appear and upsurges persist and so it seems important to understand how Facebook shapes how we process and navigate important information and ways the digital space has and may continue to provide coping mechanisms during global and personal crises.

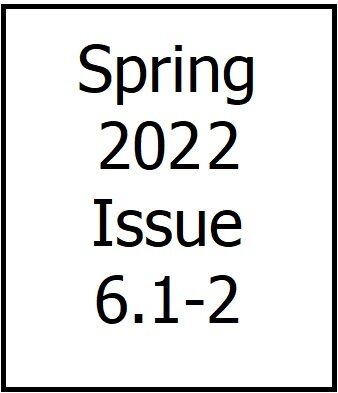

Neighborhood walks and occasional photos of blooms — particularly to mark the start of spring or a break from my normal teaching schedule — were not new practices for me. But these walking photo shoots became a daily occurrence during the Covid lockdown and seemed to mark nothing but repetition. The public performance of my daily quarantine walking ritual, captured in image clusters like the post below, was reenacted all over the world by all kinds of folks during lockdown. Users like me took seemingly meaningless and random strolls, captured images of flowers, animals, and rare sightings of others in the distance and then came home to our computer screens to curate and make sense of what we’d seen.

Such rambling movement combined with observations and the need to be somewhat visible during these walks has reminded many scholars of the flâneur, a term for a 19th-century “stroller” or “loafer” moving specifically through the metropolitan streets of Paris. While this literary term is usually associated with wealth and almost immoral idleness, this modern re-emergence of the flâneur feels somewhat more egalitarian as strollers marking their journeys on Facebook come from a variety of socio-economic backgrounds and are no longer confined to the city. While the flâneur of old chose to be idle, during the pandemic our options to be productive — for those not serving on the front lines of healthcare, food production and distribution, and other critical services — were removed and so #rural flânerie might be described as forced leisure masquerading as productivity.

|

|

Figure 1: Three images of flowers.

|

French poet Charles Baudelaire — and later German philosopher Walter Benjamin — popularized this figure and describes the flâneur as “by nature a great traveler and cosmopolitan” (Baudelaire, 1965, p. 6) and as one who “wants to know, understand and appreciate everything that happens on the surface of our globe” (p. 7). Armed with curiosity and an ability to find beauty in everything, Baudelaire’s flâneur resists the consumerist aims of the mainstream art world, but his wanderings are nevertheless important and the resulting works are signed not with a signature but “with his dazzling soul” (Baudelaire, 1965, p. 5). Posts created by modern Facebook users would certainly not be designated as art by most viewers, but such attempts to capture fleeting beauty are not meaningless. Taking images while walking and posting those images makes a stroll feel less passive and more agentive and helped the quarantined simultaneously see and be seen by others.

This article first investigates the history of the flâneur — and the related gendered flâneuse — and then locates this 19th-century phenomenon in the modern pandemic era. Next, the piece examines the unique relationship between #CovidWalking and other popular hashtags used to describe the lockdown activity and the need to document it on Facebook.

|

|

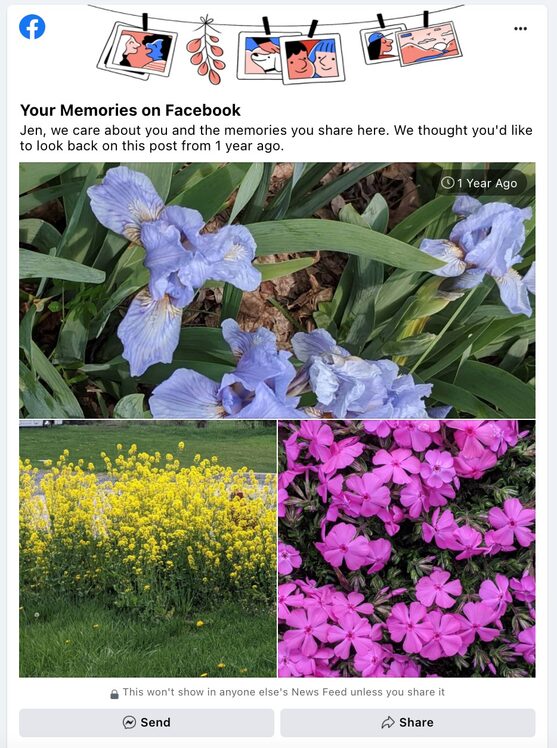

Figure 2: Stream and purple flowers.

|

Through analysis of my own Facebook posts from the lockdown in Spring 2020, like Figure 2 of a stream in a park about three miles from my home and archived for me via the Memories function of Facebook, this piece investigates the curious connection between digital and natural spaces. As scholars have rejected or worked to expand the gendered (McGarrigle, 2013), abled (Serlin, 2006), and classed (Kern, 2021) notions of the flâneur, and still others seek to expand the locations flâuneurs trod from cities to national parks (Sandilands, 2000) and our own neighborhoods, this project expands notions of flânerie in digital spaces. I argue that online pandemic flâneurs are closer to the original definitions of the term than many other modern flânerie examples in that they observed and wandered but also analyzed, categorized, curated, and recorded their experiences by posting them on Facebook. I invite readers to stroll through my pandemic Facebook feed and join me on some of my digital wanderings in an effort to better understand ways cyberflâneurs in the Age of Covid were seeking out and sharing beauty in the ugly days of the pandemic.

A Term in Transition

The flâneur is a widely known literary concept originating in France in the 19th century. The flâneur — always male and moneyed — wanders bustling city streets with no other aim than to observe contemporary life. This symbol of modernity critiques industrialization while simultaneously celebrating affluence and ambivalence. The concept, now transfigured into cyberflânerie, the feminine flâneuse, and any number of other embodied and in-place iterations, became a topic of scholarly interest in a variety of fields thanks to the work of Baudelaire, who identified the flâneur as a poet and “painter of the passing moment and of all the suggestions of eternity that contains” (p. 5). The flâneur was often presented as a detached and dispassionate narrator to usher readers thought scenes of urban life and capitalism. Eric Tribunella (2010) explains, “As the embodiment of the critical observer, the literary figure of the flâneur provides a useful device for unfolding the city before the reader and for transforming it into a thing of aesthetic and critical contemplation” (p. 66). This observation was always tied to the idea of mobile bodies moving throughout spaces with other associated terms like “strollology” (Burckhardt, 2015) and “promenadology” (Fedtke, 2021) thus elevating “the art of observation and reflection while walking” (Fedtke, p. 2) to a critical lens for observing and making sense of the world. While terms like “derive or drift” (Rose, 2021) and the modern Urban Dictionary term “coddiwomple,” meaning “to travel in a purposeful manner towards a vague destination,” can also be applied to flânerie, the focus on critical observation and contemplation while one wanders is vital. It is, perhaps, the focus on this on-the-move, in-the-moment observational sense making that has given this term such enduring power and applicability in all kinds of scholarship and settings.

Scholars from multiple disciplines — including mobility studies, computer science, digital humanities and disability studies — have laid claim and contested the term in recent years. The male-centric and classist figure has been dismissed by contemporary scholars like Conor McGarrigle (2013) who argues that “it is time to forget the flâneur, as this nineteenth century model of male privilege no longer fits the purpose” (p. 1). McGarrigle’s piece is a reaction to the growth of the term “cyberflâneur,” a “new incarnation” of the literary figure many now see as “traversing the streets armed with location-aware devices, observing and studying the augmented hybrid spaces of the city” (p. 1). For McGarrigle the flâneur is an “overextended … concept” (p. 3) whose privilege is out of step with our world. Similarly, Mariana Charitonidou (2021), a specialist in urban planning, argues for awareness of the female-focused flâneuse as she considers flânerie via the lens of feminist geography in the wake of Covid. The work of Charitonidou and others (Frank, 2020; Kern, 2021; Elkin, 2017) to center women’s walking and observing habits as meaning making is a direct response to Baudelaire and Benjamin’s inability to “notice women” (Charitonidou, p. 1) or value their knowledge creation in similar ways to male counterparts. Leslie Kern, who chronicles a new awareness of gender she experienced during and following her pregnancy, explores the ways her experience as a “mommy flâneuse” (2021, p. 32) differs from the historic model of the flâneur. “As a woman, a complete sense of anonymity or invisibility in the city had never fully existed for me,” she explains. “Nonetheless, privileges such as white skin and able-bodiedness gave me some measure of invisibility” (p. 29). Kern found her pregnant flâneuse body — and then one joined by a baby and eventual toddler — was constantly surveilled and often unwelcome. “It’s hard to play the detached observer when the fleshy, embodied acts of parenthood are on full display” (p. 32). Kern reiterates that while “some see the model of the flâneur as an exclusionary trope to critique,” others see it “as a figure to be reclaimed” (p. 29).

While McGarrigle (2013) and others have argued for new terms, many scholars have expanded and reimagined this dated figure in our modern age. David Serlin (2006), for example, an associate professor of Communication and Science Studies, considers the flâneur from a disabilities studies standpoint as the model is “a paradigmatic example of the modern subject who takes the functions of his or her body for granted” (p. 198). His article, “Disabling the Flâneur,” takes as a starting point a photo of famed advocate for the blind Hellen Keller window-shopping in Paris during the late 1930s to challenge and expand our notions of the normatively non-disabled flâneurs. “Recoding the possibilities of disabled experience — in the streets, on the sidewalks, and in every public space between — as vital components of urban modernity helps us understand these photographs in ways that are both consonant with and departures from the familiar representational rhetorics of disability” (Serlin, 2006, p. 206). For Serlin and other scholars, expanding our notions of who and how flâneur is performed revitalizes the limiting term and makes room for more inclusive depictions of the modern subject. Rather than continuing to marginalize based on mobility, such reframing might center other ways of moving through and experiencing spaces.

In another re-framing of the familiar term, Catriona Sandilands (2000) expands the reach of the urban flâneur to natural settings in her discussion of “A Flâneur in the Forest?” and recasts a national park as a “designated ‘nature’ boulevard” (p. 39). Sandilands imagines those who walk in nature as a sort of social scientist investigating the space and those in it. “In many respects the good sociologist, the flâneur thus strolls with a combination of reflexive self-location, acute observation, and historical desire in mind, these elements do not prevent him/her from dreaming along with the consuming crowds of which s/he is a part…, but they do signal the possibility of immanent moments of jolting, poetic clarity on occasion” (p. 42). Chris Jenks and Tiago Neves (2009) similarly locate the flâneur as a metaphor for both city and ethnographic research. Jenks and Neves counter that although many define the flâneur as one “who walks without haste, at random … such definitions have tended to identify the flâneur with futile dandyism and idleness” (p. 1). The authors elevate flânerie saying, “the observation of the trivial, the ephemeral and fleeting should lead to a critical analysis of the structural features of urbanity and modernity” (p. 2). For Jenks and Neves and many scholars, the flâneur is uniquely positioned to understand and interrogate the world around them simply by slowly and purposely moving within it. This blend of mindful awareness and observation coupled with a lack of specific destination suggests that the concept of the flâneur may be perfect for considering the flower-filled strolls taken and then captured via Facebook posts tagged with things like #QuarantineWalk and #CovidWalk. Further, digital “walks” and musing might offer more diverse options for modern flâneurs to move through physical and digital space and, in so doing, to share those spaces with others. As the early flâneur was responsible for “unfolding the city” (Tribunella, 2010, p. 66), Covid digital flâneurs unfolded and explained the foreign landscape of a global pandemic and ways the quarantined navigated this unfamiliar space.

Analysis of Facebook Hashtags

My interest in this project began like a flâneur’s rambling stroll. It focuses on my own experiences, point of view, and thick observations of a phenomenon that I think speaks both to pandemic life and also to our obsession documenting life. Like so many of us searching for routine, comfort, and meaning during the pandemic, I turned to nature. Janet Fedtke (2021), in “Pandemic promenadology,” considers ways that walking was specifically attractive to academics facing remote learning and the challenges of “unstructured time, unfamiliarity with digital tools, lack of motivation, [and] emotional distress” (p. 1). While many educators might have taken up walking mainly as an escape from Zoom lectures and online discussions, for others like me the “much needed exercise in digital detox” (Fedtke, 2021, p. 3) seemed always to end with “proof” of my time away from my computer uploaded and shared on Facebook. Posting random images of festive mailboxes, kids’ chalk art on driveways, bees, and flowering plants somehow made my walk more real and made it seem productive and meaningful rather than a time waster. My walks — even when they strayed no farther than my own backyard like in Figure 3 — served as a sort of a “Marked Safe From” flag on Facebook to let friends and family know I was surviving the lockdown. Is this the reason so many added hashtags, joining a virtual crowd who likely would never notice them?

|

|

Figure 3: Backyard succulents and flowering plants. |

In February of 2022 — just two years shy of the start of lockdowns beginning in March and early April of 2020 when “most Americans are living under stay-at-home orders” (Thebault, Meko and Alcantara, 2021) — I began focusing on hashtags marking this practice and discovered several including #PandemicWalk, #WalkingInCovid, and #PandemicNature. The three most popular hashtags on Facebook included #LockdownWalk, with around 7,700 posts; #QuarantineWalk with 3,300 posts and #CovidWalk with only 1,100 posts (Facebook, 2022). Related hashtags include #StaySafe, #WearAMask, #InThisTogether, #PandemicMonday, #SocialDistancing, and #QuarantineLife. In line with the tradition of flânerie, I am less interested in quantitative study of this phenomenon and more in observational wonderings about the need to discover, document, and display beauty amidst the ugliness, loneliness, and fear at the height of the pandemic. What follows is a blend of autoethnography and weaving together of scholarship on flânerie, walking for physical and mental benefits, and our apparent need to fix these fleeting moments in digital images. Facebook as a hybrid boulevard trod by many digital flâneurs and flâneuses — capturing our exploration of physical spaces in virtual venues — allows us new understanding not just of the power of walking and observation for sense making, but also of ways we might interact with the textual reminders of those wanderings. In his discussion of cyberflânerie, Featherstone (1998) explains: “The reader is invited to stroll down the street, to indulge in a little textual flanerie. The flâneur, then, is not just the stroller in the city, something to be studied. Flanerie is a method for reading texts, for reading the traces of the city. It is also a method of writing, of producing and constructing texts” (p. 910). Using my own experience and postings as a rural and digital flâneuse, I invite readers on a “little textual flanerie” to better understand my own #CovidWalk rituals and the need to publish bits of those walks for others. Using my own posts as destinations throughout the text — retrieved from the “Memories” function on my personal Facebook page two years after the Spring lockdown of 2020 — I consider ways #CovidWalk posts move among digital crowds while “walking” in digital spaces to create purpose and meaning in the pandemic, specifically by capturing ephemeral moments of beauty in defiance of pandemic pain.

Cyberflânerie on Facebook

McGarrigle (2013) not only sees the flâneur model as troublingly sexist, she also argues that the essential traits of anonymity and spontaneity are unavailable to users online. “For platforms such as Facebook, any possibility for flânerie has been successfully engineered out,” McGarrigle argues (p. 1). “To be digital involves leaving … traces; thus the flâneur’s treasured anonymity and ability to watch unnoticed are replaced, for the cyberflâneur, with not only a lack of privacy, but also the commercialization of his data trace as user-generated content” (p. 3). While it is true that almost none of us are anonymous online or off anymore — thanks to always-on devices like smartphones and Fitbits — adding images to Facebook does not necessarily destroy privacy. Like the flâneurs of old, Facebook strollers are at once part of a crowd of users — particularly if they add hashtags — and also move along fairly unnoticed as their often faceless images of plants, birds and bugs, interesting trash, and other innocuous forms garner little attention, except by close friends to whom they are already known. And while the flâneur of old was certainly able to pass unseen more often than we are now, even then flâneurs occasionally sought recognition — and some financial benefit — by publishing their observations. Featherstone (1998) explains, “When the flaneurs sought to realise his accumulated cultural capital by writing feuilletons — occasional pieces for magazines and newspapers — it was clear that he did not lack an audience” (p. 913). So while anonymity during the flâneur’s walk remains a benchmark of the practice, publicly sharing one’s findings is not necessarily in conflict with the goals of flânerie. Cyber settings like Facebook, then, collapse notions of anonymity and the desire to be seen just as they have long collapsed supposed divisions between private and public spaces and practices.

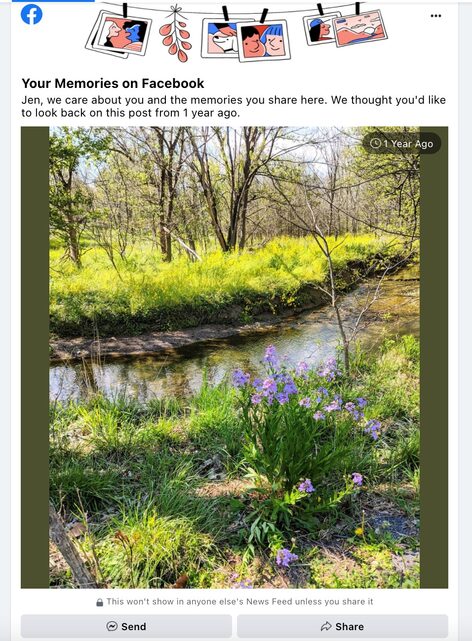

Figure 4: Five visible of eight images of nature including a duck and flowers.

Virtual Community/Crowds

While anonymity is generally considered vital to a flâneur or flâuneuse’s existence, so too is the need for a crowd to move among. Facebook, with connections to “friends” near and far and the ability to join larger groups via hashtags and communal profiles, provides just such an experience for cyberflâuners. The loss of physical crowds and community was keenly felt during the pandemic lockdown (see the image above where I attempted to befriend ducks on one of my walks) and social media and digital content became a surrogate for many of us. The isolation we experienced seemed lessened somehow by knowing others were experiencing it too and the anonymity so often desired by the cyberflâneur morphed into a desperate need to be part of something bigger than ourselves. While McGarrigle (2013) argues that Facebook erases a flâneur’s much-needed anonymity (p. 3), many of the posts I encountered where created by those anonymous to me in that I reached them only via hashtag and not through other linkages. This, in effect, rendered lockdown walkers nearly invisible as the focus for viewers is on the images rather than the walkers themselves. My focus, and theirs, seemed to be on the scenery and world around them. Those strolling Facebook during the Covid lockdown continued the tradition of observation, movement without real agenda, and attempts to make sense of the historic cultural moment. And while seeking belonging in a way that historic flâneurs perhaps did not, Covid flâneurs and flâneuses were moved by the same desire to escape to crowds that could not be found in their apartments and houses.

For Baudelaire and Benjamin, crowds provide the flâneur with security and refuge. Baudelaire explains that for the flâneur, “the crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd” (p. 9). And for Benjamin meaning for the flâneur comes in “traces” and objects and observation that provide “shocks” to the viewer moving along with others. David Ferris (2008) explains, “Benjamin describes an urban existence in which experience is defined in the form of trace that disappears into the crowd from which it has emerged” (p. 126). Without the luxury of getting lost in crowds in shopping malls, busy city streets, or rural farmers markets, those in lockdown sought the comfort of virtual crowds and communities. While Charitondiou (2021) understandably claims “the practice of flânerie has been threatened by the pandemic” (p. 1), I maintain it has only expanded the scope from urban to rural areas with observations and images posted online making pandemic flâneurs a part of an unseen, teeming crowd of other walkers searching for meaning and belonging. Though Facebook flâneurs cannot be swept along physically by bustling crowds, the presence of hashtags and likes bears witness to one’s walking and meaning making.

![A Facebook post from a year ago, featuring a dogwood tree covered iin white blooms. The caption reads, Thankful today for the neighbor's beautiful dogwood . Great view from my bedroom window. [heart]](/files/resized/103264/598;592;f24598c1f641e59a148ff7c645a5dd66565ba543.jpg)

Figure 5: Flowering dogwood tree.

“Walking” in Digital Spaces

The ability to stroll virtual byways and see new sights was critical during lockdown when we were confined to our private physical spaces. In the image above, for example, it felt insufficient for me to enjoy the scenery of my neighbor’s backyard visible from my bedroom window until I documented it and curated those images for others on Facebook. This act stretched the boundaries of my available and isolated space and invited others to share my view when I could not invite them into my physical home or yard. Digital connection in the face of loneliness is hardly a new topic. In a 2020 post considering “the role of technology in combatting social isolation in older people,” academic blogger Shailey Minocha considers specifically ways the elderly leveraged the power of walking and sharing images of walks on Blipfoto as a means to combat the confinement caused by the Covid lockdown. Minocha notes the activity encouraged participants to “connect, be active, take notice, keep learning, and give.” While Minocha focuses on a more directive agenda for walking and posting photos for a smaller, more specific audience, this example seems a microcosm of Facebook posting that reaches a potentially, but not necessarily larger audience, but is similarly invested in curating experiences of movement via photography. In a similar discussion of pandemic walking to build community and knowledge, sociology professors Lauren White and Katherine Davies (2020) invited colleagues to photograph and make notes about walks. For the authors and their colleagues, taking a walk served as “a pocket of freedom” and the images the group shared of family walks, accounts of nature, and “sensory experiences of urban and rural places” provided “proxy for personal discussions and a way into talk about shared everyday sensitivities,” they explain in their digital article. The same need to experience, share, and discuss walks, perhaps in an effort to make sense of the confusion and fear surrounding the pandemic lockdown, is what fueled so many #QuarantineWalk posts, though without a research agenda or trained researcher’s eye.

Online pandemic flâneurs, then, are faithful to original notions of the term in that they observe and wander but also analyze, categorize, curate, and record their experiences through posts. While several scholars focus on walking itself as strategy for “improving both mental and physical wellbeing” (Fedtke, 2021, p. 1), researchers Tu, Hsieh and Feng (2019) focus on walking as a coping tactic during COVID in concert with digitally documenting such walks. While physical activity is foregrounded in this sports management journal article, the scholars consider ways “emotional value and social value” (p. 684) must both be met to encourage walkers to continue fitness activities and they feel that “virtual rewards” (p. 685) — such as Facebook likes — provide both emotional and social rewards for walkers. Focusing particularly on social connection and feedback seems the most promising to the researchers as “effective in physical activity interventions” (Tu, Hsieh and Fend, 2019, p. 691). While seeking feedback might seem counteractive to the flâneur’s historic aim of moving unseen, framing one’s experiences and insights as part of a larger cultural conversation has long been the flâneur’s purview. Akin to the “occasional pieces for magazines and newspapers” (Featherstone, 1998, p. 913) called feuilletons, pandemic walkers share insights from their wanderings as both a strategy for accountability and also as a way to designate this activity as in some way important or noteworthy.

Critical engagement and awareness of space is bedrock to the act of flânerie. Featherstone (1998) explains that the flaneur “develops his aesthetic sensibility in the swings between involvement and detachment, between emotional immersion and decontrol and moments of careful recording and analysis of the `random harvest’ of impressions from the streets” (p. 913). Like flâneurs of the past, #CovidWalks demonstrate no set path or goal, but many acknowledge the general intention of combatting isolation and also offer tools for personal understanding of a confusing cultural moment. While historic flâneurs wandered slowly in defiance of the pace of industrial life (Featherstone, 1998), pandemic walkers moved in defiance of boredom and idleness and also, perhaps, of lockdown orders. For Rose (2021), walking guided by an awareness of physical space and movement “transforms the everyday act of walking into a research tool” (p. 101). As part of a walking group that used technology for mapping synchronous but distanced walks, Rose and her group focused less on documenting the walk and more on taking it together. While Rose worried that “being distracted by a smartphone prevents participants from being fully present” (2021, p. 104), I argue that smartphones, in this case, might actually sharpen focus and attention. Choosing exactly where to point the camera and how to compose an image via angle, distance to subject, and other compositional elements forces walkers to attend to and mark certain moments rather than merely moving through them. Critical awareness of one’s space, movement, and the sensory experiences and emotions evoked by such is a requirement of curating a walk in images.

Figure 6. “Better Together” chalk driveway art.

Purpose and Sense Making in the Pandemic

Walking and moving with the critical awareness necessary to compose and capture photographs offers opportunities to make meaning and sense from seemingly innocuous moments, particularly in times of crisis and fear. Information technology scholar Lavinia Marin (2021) explains, “the user’s need to post content as a way of making sense of the situation and for gathering reactions of consensus from friends” (p. 1) was particularly salient during the Covid lockdown, when so many of us felt so isolated. According to Marin, light-hearted posts like those of #PandemicNature might also help us avoid information overload, particularly when so much of that pandemic-related information circulated in digital spaces like Facebook was terrifying and often misleading. “The pandemic was reflected in the online realm of social media by a flood of redundant information (the so-called infodemic) out of which a significant percentage was made up of misinformation and disinformation,” Marin explains (2021, p. 1). For users faced with a relentless stream of memes, personal blogs, academic and medical articles, announcements from the CDC and from individuals — all presented as having pretty much the same importance and credibility — this “creates information overload which leads to information fatigue” (Marin, 2021, p. 2). Seemingly meaningless images shared by Facebook flâneurs then are important as an antidote to this infodemic as they meet the social needs of users — reminding us that we are #InThisTogether but not making major claims to safety or diagnosis. Andrea Frank (2020), writing about six months into the pandemic, described her 2- to 8-mile daily walks during lockdown as having “a distinctly flâneur-like aspect to them with the observant stroller exploring the environment” (p. 27). Frank captured images of her walks — including roped off playground equipment, people standing feet apart in line and general emptiness — and found herself contributing to “stark images of deserted public squares, roads and streets making the news around the world” (p. 26). Curating such images and later “re- visiting these images” Frank explained, allowed “an idiographic approach … to examine the phenomena experienced” (p. 28). Though vastly different from my Facebook feed, made up of neighbors in rural Virginia and colleagues in a variety of mostly small towns scattered throughout the country, Frank’s images of urban desolation and eerie quiet provided the same overall result — a way to process what we as individuals and communities were experiencing. Capturing these images allows a certain measure of agency when endlessly and passively consuming the warnings, insights, and theories of others.

The desire to visually document the spaces around us is clearly not limited to the pandemic. Cartiona Sandilands (2000), writing two decades pre-pandemic, argues that capturing images of nature are purposeful and powerful distractions in our always-on and connected culture. Sandilands first positions parks — which enjoyed a surge in popularity during and following pandemic lockdowns — as designed to be consumed (p. 44). “The flânuer is the consumer to whom nature is offered and organized as consumable,” Sandilands explains (p. 53). And like Facebook itself, parks are highly regulated and organized and yet, for Sandilands, defined walks and paths do not exclude natural parks from flânerie. While the “spatial regulation” (Sandilands, 2000, p. 47) of parks plead with visitors to stay on marked paths with others rather than wandering alone, “the flaneur is absolutely at home in the crowd and removed from it at the same time,” Sandilands explains, and “the ability to be both himself and other, to both recognize and interrupt the conditions enabling his walking” (p. 38) may create in the park flâneur new insights and critical awareness of natural spaces. The forced interruptions of trails and signage does not rob the flâneur of his ability to dream, but, like stopping for photos on a neighborhood stroll, might provide brief, jolting awareness of one’s position and mindset in a moment. Digital flâneurs, while no longer free to roam the entire Web like in early geocities days, stick to the digital paths laid out in places like Facebook, but such paths need not discourage wandering, self-reflection, observation, and the traces and shocks Benjamin identified as vital to meaning making (Ferris, 2008).

Figure 7. Five visible of nine images of flowering trees.

Capturing Moments of Beauty

While images of strange emptiness and quiet, like those captured by Frank (2020) on her walks, were indeed fascinating and widely shared online, I am most interested here in the sharing of the more mundane. Images of small animals, plant life, and sunsets appear to offer fewer important insights, but the focus on rural rather than urban spaces by pandemic flâneurs and flâneuses seem related both to our ingrained practice of consuming nature, as noted by Sandilands (2000), and also due to the inaccessibility of many urban spaces thanks to the need for social distancing. While rural spaces emerged as bucolic and beautifully untouched by humans during lockdown, urban spaces took on an apocalyptic tenor. In the face of jarring and impressive urban images, there seems a desire to find simple and unchanged beauty during the dark times of the pandemic. This need to codify beauty — whether natural or human or industrial — is another marker of early flânerie. Eric Tribunella (2010) explains:

In short, the flâneur is to find and to translate the beauty of the present, of the modern age; he does this by strolling through the streets of the city, being among the crowd, and gazing upon all that the modern age makes possible. He combines a critical eye with the artistry of the painter or poet. (p. 65)

Tribunella positions the flâneur figure as akin to that of a child in literature and in life as both are often unnoticed in a crowd, endlessly interested in what others take for granted, and able to uncover beauty in unexpected places. While children, and women for that matter, historically enjoyed less access to public spaces, the concept of flânerie hinges on the ability to find joy and discovery in the mundane and this curiosity is associated deeply with childhood. “The flâneur, exhibiting qualities of both the convalescent and the child, approaches the city with this keen sense of interest that enables him to see through its filth, incoherence, and chaos to its beauty and diverse possibilities” (Tribunella, 2010, p. 67). The ability to locate unexpected joy and visual pleasure in the dark early days of the pandemic seems especially necessary as a coping mechanism.

As several scholars, including Chris Jenks and Tiago Neves (2000) remind us, “a present day flâneur is, or perhaps we might say 'should be', more attentive to questions of gender and ethnicity” (p. 15), it is also important to be more attentive to ideas of privilege. Those of us with time and the ability to capture beautiful images on Facebook clearly enjoy fiscal security enough to afford a smartphone or similar device as well as the time to stroll and take and later arrange images. We also were likely not front-line workers like nurses, grocery store clerks, and security guards and police officers who both personally experienced the horror and loss of the pandemic and also were likely less able to stop enjoy moments of beauty. However, even for those of us not personally handling the atrocities of the pandemic, anxiety and fear were very real and in the midst of the ugliness and loss that marked so much of 2020, the ability to find beauty and peace in the mundane was indeed a survival skill. It’s important to remember that the ability to engage in such walks was made possible by the labor of those serving during quarantine. And continuing to look for beauty in dark times may help us reframe Facebook posts from mere navel-gazing or “braggy” posts to tactics of resistance both for the poster and their followers. In the restlessness and vulnerability that defined the pandemic, taking images of nature while in sanctioned safe and isolated spaces turns the socially-distant walker into a flâneur who explored spaces of “aesthetic and critical contemplation” (Tribunella, 2010, p. 66) seeking momentary escape from worrying about or being trapped by a global pandemic.

Conclusion

Just as #LockdownWalk-ing allowed many of us to make sense of the bewildering and frightening quarantine days, walking through months of my Facebook posts from those days illuminates how digital spaces work in embodied and critical ways to help us make sense of our own experiences. Reframing what I considered, at the time, throw-away content and narcistic glimpses of my life as a legitimate coping strategy and having some communal worth might also impact my goals for digital media and my classroom. Sharing images of beauty from a beach or lovely lighthouse on vacation, for example, might be recast not as bragging or performance of perfect-seeming lives but instead as an earnest effort to combat the ugliness that has come to characterize so many of our online spaces and communities. Such personal and purposely mundane and trivial moments are important antidotes to the ceaseless stream of information jockeying for positions as “right,” “important,” and “incontrovertible.” While we often teach students to seek out sources that are vetted and verified, personal posts like those made commemorating #CovidWalk(s) can make no such claims. But they are not unimportant. Learning to value our own experiences and points of view — while also attending to ways such moments are experienced by others — might be an important literacy skill we offer students and other digital consumers. We run the risk now of being swept up in the crowded digital marketplace of ideas, but making time to critically attend to our own movement and motivations may help us resist and navigate the sea of information rushing around us. Like flâneurs who are “absolutely at home in the crowd and removed from it at the same time” (Sandilands, 2000, p. 38), fostering digital flânerie in both physical and virtual-only spaces may allow us to consume the abundance of information we are offered online while not merely floating along in whatever direction others’ information takes us. Valuing and nurturing awareness of our own located and embodied selves (both physically and virtually) may provide refuge from information overload by giving us a space to start from and return to. Learning to value and see the beauty in both our own and others’ experiences and understandings is vital to learning and using new knowledge rather than just letting it wash over us.

References

Baudelaire, C. (1995). The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays. 1863. Londen en New York.

Burckhardt, L. (2015). Why is landscape beautiful?: The science of strollology. Birkhäuser.

Charitonidou, M. (2021). The practices of flâneuses within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: Feminist geography vis-à-vis automation discourse. In V Congresso Internacional Arquitectura e Género| ACÇÃO. Feminismos ea espacialização das resistências (2021). ETH Zurich, Chair of the History and Theory of Urban Design.

Elkin, L. (2017). Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice, and London. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Facebook. (2022, March 9). Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/hashtag/

Featherstone, M. (1998). The flâneur, the city, and virtual public life. Societes, 153(3), 19-46.

Fedtke, J. (2021). Pandemic promenadology: walking for wellbeing in academic life. Journal of learning development in higher education, (22).

Ferris, D. S. (2008). The Cambridge introduction to Walter Benjamin. Cambridge University Press.

Frank, A. I. (2020). Observations of a pandemic flâneuse: Behaviour change and adapting public space in Birmingham, United Kingdom. disP-The Planning Review, 56(4), 26-33.

Jenks, C., & Neves, T. (2000). A walk on the wild side: Urban ethnography meets the flâneur. Journal for Cultural Research, 4(1), 1-17.

Kern, L. (2021). Feminist city: Claiming space in a man-made world. Verso Books.

Marin, L. (2021). Three contextual dimensions of information on social media: Lessons learned from the COVID-19 infodemic. Ethics and Information Technology, 23(1), 79-86.

McGarrigle, C. (2013). Forget the flâneur. Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Electronic Art. Sydney, Australia. doi:10.21427/bezf-s927.

Minocha, S. (2020, April 9). The role of technologies in combatting social isolation in older people due to COVID19. Shailey Minocha. https://www.shaileyminocha.info/blog/tag/older+people

Rose, M. (2021). Walking together, alone during the pandemic. Geography, 106(2), 101-104.

Sandilands, C. (2000). A flâneur in the forest? Strolling Point Pelee with Walter Benjamin. Topia: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies, 3, 37-57.

Serlin, D. (2006). Disabling the flâneur. Journal of Visual Culture, 5(2), 193-208.

Thebault, R., Meko, T. and Alcantara. J. (2021, March 11). A pandemic year: Sorrow and stamina, defiance and despair. It’s been a year. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/interactive/2021/coronavirus-timeline/

Tribunella, E. L. (2010). Children's literature and the child flâneur. Children's Literature, 38(1), 64-91.

Tu, R., Hsieh, P., & Feng, W. (2019). Walking for fun or for “likes”? The impacts of different gamification orientations of fitness apps on consumers’ physical activities. Sport Management Review, 22(5), 682-693.

White, L., & Davies, K. (2020, November 25). Our lockdown walks: Physically, but not socially, distanced walking as method. The editor’s notebook, International Journal of Social Research Methodology. https://internationaljournalofsocialresearchmethodology.wordpress.com/2020/11/25/our-lockdown-walks-physically-but-not-socially-distanced-walking-as-method/