On Digital Forums and Community Support During COVID: A Reflective Account

Florence Elizabeth Bacabac

Keywords: music; YouTube; international workers; online community; cultural support; cultural identity

Categories: Bearing the Weight of Racism through Anti-Racist Work and (Cross-)Racial Solidarity; Arting/Crafting/Making in a Crisis; Building Community in Isolating Times

In the summer of 2021, I was flipping through the pages of a magazine and came across a small section on tips for practicing self-care. While the list focused more on reducing stress for those on the job market during COVID, one of its bullet points got my attention: "Create a good support network. Others who have been in a similar situation are often willing to help" (Judd, 2021, p. 26). I thought, Well, that's interesting. I may not have created one for that purpose during the pandemic, but I certainly looked for an online network to engage with that would simulate a mental health care regimen while I virtually taught, conferenced, and graded papers. For me, this digital community network was Tambayan Alley (TA), a synchronous/interactive forum on YouTube hosted by immigrants from the Philippines that became a solace for most overseas Filipino workers (OFWs). As a US-based writing teacher born in the Philippines, TA on weeknights was my happy pill.

The pandemic lockdown of March 2020 brought the world to a standstill, and we witnessed how global economies, healthcare institutions, social support/services, and so on were negatively affected. My full-time job in southern Utah continued to give me economic stability, but my mental health languished without the regularity of F2F interaction and communal meetings. When most classes moved from F2F to virtual (or HyFlex) modes, I spent more time remediating lesson plans, grading online papers, and Zoom conferencing with students and less time tending to my own personal/professional needs. These pandemic barriers affected my productivity and would have, ceteris paribus, continually reduced my output if they were left unhindered. International workers are more susceptible to depression, loneliness, and isolation, which are exacerbated with community quarantine restrictions. However, the impact of cultural support groups like TA for OFWs was immense, serving another type of online carework for the marginalized with displaced sociocultural identities. Based in California, the content of TA episodes during COVID harnessed the saving grace of digital forums, cyber-cultural organizations, and multimodal ecosystems that reaffirmed cultural identities, social networks, and personal interests. For me, TA came at the right time and inspired me to soldier on through the pandemic.

Around mid-December 2020, I found myself surfing on YouTube after my fall semester final grades were submitted, and I came across the channel of Paco Arespacochaga, a US immigrant and drummer of the Filipino rock-band Introvoys. He had a livestream with two of his friends—Joseph Bayan (head of Bayan Promotions, an online ticket sales company in North America) and Bryan Elazegui (another immigrant and former drummer of 3Days, Slide and Goodbye Tracy)—and they were testing out Paco's new Ecamm for his digital show Paco's Place that features Filipino and international artists from around the world. Since I didn't have anything to do that night and needed to decompress, I decided to join the TA livestream dialogues. What was interesting was that the hosts pitched topics that resonated with Filipinos and made things more interactive by reading off comments, greetings, or shoutouts. They also played and danced to a signature background music for every SuperChat received (i.e., monetary donation). Before I knew it, the first session was over and what would have been another monotonous evening turned out to be a fun night. I felt more energized the following day to work hard, finish early, and join the next episode, which became my weekly routine until spring 2021 semester. I didn't realize the negative social impact of this pandemic until TA was launched, so I became a regular participant not only for the emotional boost of actively engaging in a community but also for the instant connection with the hosts and fellow tambays [those who hung out regularly in real-time].

Reflection

Digital forums on YouTube like Tambayan Alley enable those with similar cultural backgrounds in different locations to relieve stress and interact on livestreams across multimedia platforms (e.g., text, video, audio). In retrospect, I would like to highlight the following characteristics of online communities, cultural support groups, and multimodal carework as a result of my participation in TA around the first half of 2021:

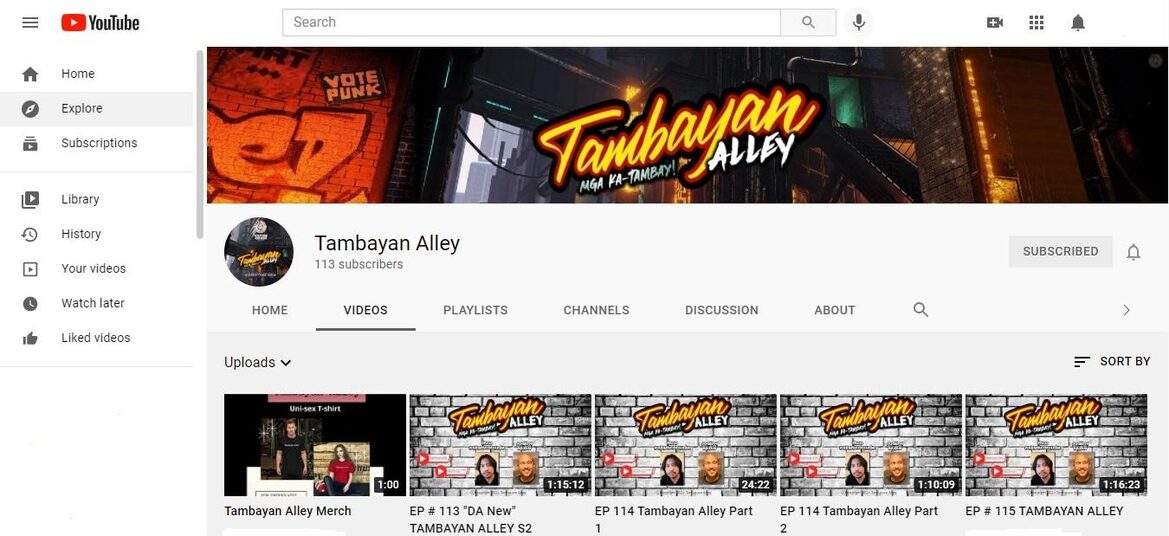

Online Communities Reduce Isolation. Although online groups may not be appropriate for everyone, they still provide alternative options for those who would like to get connected in real-time, meet new friends, and reduce their sense of isolation (Gary, 2001). The trauma brought about by this global pandemic prompted some netizens living abroad to search for online communities to facilitate contact with people from back home. Because Utah also experienced the negative impact of COVID, especially on women in the workforce (Christensen et al., 2021; Hansen et al., 2021), I found the impetus to engage in digital networks. I am quite certain that while others found support in various cyber group settings, I found mine in Tambayan Alley where participants could freely communicate in a safe environment (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Screenshot of YouTube channel titled Tambayan Alley with thumbnails of video episodes.

The word tambayan stands for “hangout place” and these types of cyber-connections allowed me to engage in meaningful conversations through our hosts' focused guidance. Along these lines, the development of new social relations was made possible, transforming the role of the Internet to a social networking medium beyond that of information access.

I also noticed that as virtual relationships were formed, more participants joined TA because of friends, co-workers, and neighbors who recruited them from other networks. Others followed TA due to their affiliations with one of the hosts' Facebook pages or YouTube channels or as loyal network subscribers of Paco's band, Introvoys. Paco said it best in episode #117: "TA keeps people company while they're at work. . . [its] intent was to connect people together, to touch their lives, and uplift them" (personal communication, June 28, 2021). Joseph, one of the co-hosts, agreed by stating that the livestreams could "help others make true friends and serve as another diversion during the pandemic" (personal communication, June 28, 2021). Everyone who joined this weekly program, including the hosts' wives Jaja Arespacochaga and Mary Ann Bayan, willingly shared their thoughts/opinions about making friends as evident in the following insights from katambays [fellow TA participants]:

- "What I like about TA is that it is incredibly engaging, allowing viewers, guests, and hosts to connect in a way that made us feel like one huge barkada [group of friends]."

- "[I love the] friendships formed in TA."

- "TA keeps me company [and helps me] make new friends."

- "I made lots of new friends all over the world [through TA]." (trans.)

- "I'm grateful for having friends online because we were in a lockdown and we couldn't go out. Our world became bigger instead of smaller [due to TA]. Those friends even helped me with my child who needed therapy. They were generous (. . .) I think there were more benefits that happened to me but these are the most important ones I can think of."

These sentiments only reinforce the notion of how online communities tend to break social barriers, allow global connections, and foster a sense of belonging, especially during COVID. Our perceptions of social reality are being altered by the emergence of organized communities, bridging physical detachments and helping us build new relationships across continents.

Cultural Support Groups Affirm Cultural Identity. While online communities reduce isolation, a sense of group identity is also being formed virtually. Each Tambayan Alley session opened up a digital space for overseas Filipino workers to relate their cultural experiences, beliefs, mores, and so on with like-minded individuals. Communicating through media technology helps develop a virtual group identity for those in multiple locations (Baltezarevic et al., 2019), and since its members were from the same culture, TA instantly became a venue for an organized brand of support. The appeal of moving toward our local cultural identity (vs. diverse cultural identities) was intensified in this virtual forum to counter homesickness or boredom just as our common geographical origin, history, and language enhanced shared experiences over our lingua franca, Tagalog. Sometimes a few Filipinos from a specific region might use their vernacular language (e.g., Hiligaynon, Cebuano, Bicolano) in the chat room, but they would quickly switch back to Tagalog, English, or Taglish [code-mix of Tagalog and English] after each transaction to resume group communication. These sporadic cultural nuances warrant a collective sense of comfort and security, helping virtual members avoid alienation.

Current networked technologies also allow individuals to participate in the fluid process of identity formation based on mutual engagement (Guzzetti, 2008). Our TA episodes covered a wide range of topics that often led to cumulative inceptions of accepted codes/practices online. For example, life coach Paco would impart valuable life lessons from his past experiences about how to cope with loneliness, what to do in difficult situations, why certain actions are better than others, and so on. These discussion points are rife with possibilities for cultural learnings as participants negotiated en masse toward a group identity that upholds Filipino values. Other relatable topics tossed around the forum include Philippine arts/culture, original Pilipino music (OPM), Philippine street foods/libations, famous bars/restaurants in Manila, and so on. Filipinos are very passionate individuals who love music, so singing and dancing were regular staples at every session, a few of which were integrated into fun games. Some of us who have lived abroad for several years would sometimes reminisce about how things were back in the day, and the TA community never failed to offer us a safe space where we could freely share our sentiments about the motherland (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Photo collage of Tambayan Alley hosts and members chatting on episodes on January 4th and June 19th 2021.

Using an open source platform such as YouTube to exchange ideas/opinions cemented our collective Philippine values, the common denominator we could all identify with, rally behind, and get support from. In fact, the following katambays expressed their deep sense of connection to the show:

- "TA hosts Paco and Jojo share good, inspiring life lessons that I can relate to."

- "I feel so special because the hosts are very approachable and friendly (. . .) they actually treat you as a family so you are free to share your own opinion." (trans.)

- "The topics were interesting and fun so I got hooked and (. . .) I could also provide something in the conversation."

- "I really like the viewers-to-host interaction [because I can freely share my own thoughts]."

- The hosts (. . .) connected with their followers and you really felt valued with their shoutouts and roll calls every session." (trans.)

Thus, we would actually take out what we put in, given that we actively engaged online to assert our cultural roots, build group rapport, and feel supported as OFWs. Such a collective endeavor in virtual forums like this always required grit, progression, and circuitry in showing who we are synchronously from a cultural standpoint.

Multimodal Carework Enhances Reciprocity and Co-Creation. Social interactions through texts, images, sounds, or multiple modalities enhance carework as online participants navigate the pandemic. Such digital practices develop reciprocity, creativity, and co-creation in various spaces and structures. Tambayan Alley oftentimes advertised vlogs, podcasts, and livestreams that would benefit most katambays, including the promotion of user-generated productions for stress therapy. For instance, Paco is also a YouTube vlogger who sometimes used ideas from previous audience interactions to create new vlog narratives that would help others, embodying participatory content or "collaborative 'nonhierarchical' storytelling" (Deuze, 2006, p. 65). TA digital practices ratified participants as active agents in the process of meaning-making to remediate specific versions of reality (Deuze, 2006), giving them tools to receive care and returning the favor with incentives like SuperChats, BuyMeaCoffee, channel subscriptions, and livestream guest appearances. Some katambays noted the following anecdotes about TA carework:

- "TA did not only provide me with the opportunity to meet new friends (. . .), but it also helped my mental stability."

- "I like TA because it brings joy and reduces stress." (trans.)

- "TA is one of the reasons I improved myself (. . .) and it also became my stress reliever." (trans.)

- "I love the SuperChats and fun consequence games [they helped me forget my problems]." (trans.)

- "TA gave me lots of benefits. First, it became an anti-depressant. When we were hit by the pandemic and the lockdown happened (. . .), most of us got depression [and] the show uplifted me (. . .). Second was the chance to be recognized. I had a talent that I abandoned since the '90s [but] was finally revived when I became a part of TA All-Stars."

Upholding the concept of reciprocation, the TA hosts also claimed this program kept them sane during COVID. I think the multimodality of the platform just added to the transparency of benefits, care, and support for all stakeholders while leveraging the power of online communities for their general welfare.

This shift toward inclusion and reciprocity is facilitated by the synergy of technology, organization, and participants as actors involved in value co-creation (Priharsari and Abedin, 2021). Simply put, TA understood our needs for wellbeing and productivity just as businesses value co-creation with customers for mutual benefit. Reward systems were even incorporated into TA episodes at some point to increase social engagement among members through HungryJilly's raffles, Bayan Promotions' T-shirt giveaways, gift cards, and so on. Moreover, certified katambays with singing/musical talents were discovered and featured in several "Tambayan Alley All-Stars" segments and hosted their own livestreams to express their creativity as showcased in the channels of Cats and Ants, Nafsy, Lou Gallardo, 80zens, et al. (including TA member RockinCherub TV's podcast, Batang 90's Pop!). However, because the rules for online interactions change over time, online communities must also attend to the fluidity of their programming line-ups, membership variations, fluctuating episodes, hosts, and technical platforms. For example, TA went off-air for the first time since its conception on the week of June 14th (Monday) 2021 to reassess the overall intent of the program, its purpose, goals, outcomes, and so forth; after that week, the hosts decided to continue livestreaming until the end of summer 2021 and took another break while Paco’s band Introvoys traveled around North America to do concerts with Bayan Promotions. So far, TA was rebranded into Da New Tambayan Alley around June 2021, has diversified into podcasts on Spotify and iTunes around July 2021, and so on (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Tambayan Alley banners shown on Spotify (podcast) and Facebook (social media).

A new digital show, Whisky Sesh, hosted by Paco and his Paco's Place co-host Michael Abad, also came about where assorted guests/friends tasted and gave whisky reviews; though not shown as regularly as TA, I'd find some katambays in the streaming forum when Paco/Michael would go live in-between their respective shows and band gigs. Consequently, I suspect more changes to come for TA as of this writing and beyond.

Conclusion

I personally welcomed the changes that Tambayan Alley has taken thus far, even as it came to an abrupt stop around August 2021 to give way to the concert tours of our hosts. It aired for a couple more sessions in December 2021 and was totally gone in spring 2022. My involvement in the TA virtual community was both a happy accident and privilege considering that, once upon a time, this digital platform promoted social connection, cultural support, and multimodal care to its participants during the pandemic. Though these networked characteristics overlap, the fact that my fellow katambays converged on weeknights from mid-December 2020 to the end of summer 2021 brought about a renewed sense of hope, equity, and inclusion in cyberspace under the guise of reciprocity and interactivity. Since then, Bayan Promotions LLC branched out to virtual entrepreneurship by selling merchandise products (e.g., t-shirts, mugs, aprons, etc.) for TA and Tikman Natin [Let's Taste This], another online show featuring Philippine food entrepreneurs (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Photos of me wearing t-shirts from Bayan Promotions.

Adopting the same technological interface to connect with community members as prospective customers generates an increased online social capital (Chandna and Salimath, 2020), so Bayan Promotions has combined, inter alia, online advertisement, social media outreach, and community support for this purpose. Their apparel reminds me how virtual communities such as TA sustained me during COVID and how its digital forums shaped my writerly life, something that must be archived even if TA ceases to exist by the time this article is published.

Acknowledgments

I'd like to thank Tambayan Alley hosts, as well as my fellow Tambayan Alley participants, for supporting this project (you know who you are). Maraming salamat po [thank you very much].

____________________________________

References

Baltezarevic, R., Baltezarevic, B., Kwiatek, P., & Baltezarevic, V. (2019). The impact of virtual communities on cultural identity. Symposion 6(1), 7-22.

Chandna, V., & Salimath, M. S. (2020). When technology shapes community in the cultural and craft industries: Understanding virtual entrepreneurship in online ecosystems. Technovation 92-93, 1-13.

Christensen, M., et al. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on Utah women and work: Health impacts. Utah Women and Leadership Project: Research and Policy Brief (Policy Brief no. 37). pp. 1-6. https://www.usu.edu/uwlp/blog/2021/the-impact-covid19-women-and-work-health-impacts

Deuze, M. (2006). Participation, remediation, bricolage: Considering principal components of a digital culture. The Information Society 22, 63-75.

Gary, J. M. (2001). Impact of cultural and global issues on online support groups (EDO-CG-01-01). ERIC Digest. https://www.counseling.org/resources/library/eric%20digests/2001-01.pdf

Guzzetti, B. J. (2008). Identities in online communities: A young woman's critique of cyberculture. E-Learning 5(4), 457-74.

Hansen, J., et al. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on Utah women and work: Resilient mindset and well-being. Utah Women and Leadership Project: Research and Policy Brief (Policy Brief no. 36). pp. 1-5. https://www.usu.edu/uwlp/files/briefs/36-covid-19-resilient-mindset-wellbeing.pdf

Judd, E. (2021, Summer). Navigating career transitions. Thrivent Magazine, 119(699), 25-28.

Priharsari, D., & Abedin, B. (2021). What facilitates and constrains value co-creation in online communities: A sociomateriality perspective. Information and Management, 58(6), 1-15.

Bio

Florence Elizabeth Bacabac is a Professor of professional/technical writing and digital rhetoric and Coordinator of the English composition program at Utah Tech University in St. George, Utah. She teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in research, grant writing, and composition. Her articles have appeared in Computers and Composition Online, Peitho, Journal of Teaching Writing, Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, and Journal of Business and Technical Communication, among others. She is a recipient of the 2021 Excellence in Education Award from the university board of trustees and the Community Engaged Scholar Awards in 2018, 2014, and 2011 from Utah Campus Compact. For more information, visit her professional website here.