Teaching English on Zoom with Fewer Words and with Some Humor and Art

B.G. Betz, with original drawings by Jackson Betz

Keywords: online teaching, teaching as carework, art and humor in teaching

Categories: Teaching as Carework, Teaching as Dangerous Work; Arting/Crafting/Making in a Crisis

As a 30-year adjunct faculty member at WCU who is a passionate in-person classroom teacher, I have struggled—as have my students—with how to teach and learn remotely and still convey the care and connection crucial to teaching and writing. As my students appeared more and more weighed down by the stultifying monotony of white words printed on a black Zoom background, I found some success with original drawings and the occasional "art-adjacent" PowerPoint slide. Aware of how exhausted my students were from trying to process giant blocks of text on their computer screens, I used a handful of drawings of women writers confronting 21st-century tech interspersed with the occasional PowerPoint slide to convey to my students—in a less stressful manner—the fundamentals of writing. I want my students to understand that I get how challenging writing can be in normal times and even more so during a global pandemic, and that I care about their continued engagement with our class material. I use images to try to alleviate academic-text burnout, to break up the wall of words, and to remind them that the writing process doesn’t have to be grim and can even be fun. I hope to strengthen their confidence with writing through texts and images that connect them with each other and with me as they write, revise, and write some more.

Example #1: My “About the Instructor” profile picture on Zoom and on our school’s content management system (D2L) is a drawing of me as a Lego Minifigure. My students seem to enjoy the accessible, informal depiction of their professor.

Example #2: On the landing page of our D2L course site, I insert the following drawing of Jane Austen gazing askance at her MacBook. I point out to my students that the drawing depicts a woman writer of classic English literature demonstrating the same wariness of tech that we might all experience (perhaps never more so than during pandemic-induced fully-remote learning).

Example #3: Below is a drawing that I used for the first time during the Fall 2021 semester. It depicts a Victorian lady using Twitter, a steampunk mashup to catch my students’ attention and inspire discussion about different genres and their many complementary purposes for us as both academic and personal writers.

![A colored-pencil drawing in brown, tan, blue, purple, and red of a faux Twitter ad that features a back view of a woman in elegant, cascading Victorian clothing. The words in the drawing read “Twitter: Matchless with Online Community [. . .] 280 Characters.”](/files/resized/103665/763;1314;32da91f86ef62586a1372fa82d5484df58625a07.jpg)

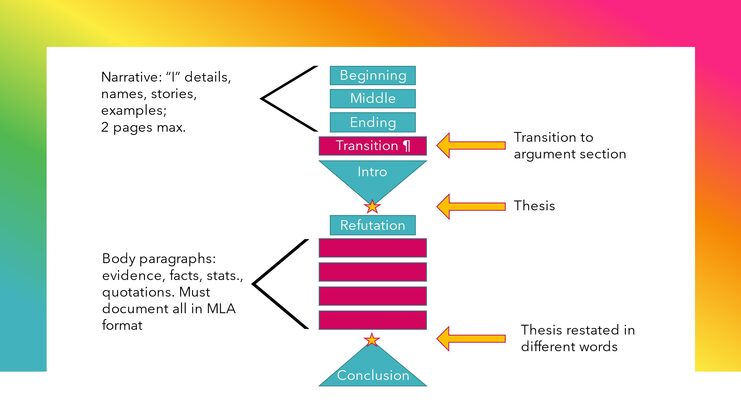

Example #4: My final example is, on the one hand, the most pedestrian of the four because it is a basic PowerPoint graphic that I have created, but, on the other hand, it demonstrates care for students stressing over the writing of research papers. It is a template for how they can organize their short research papers, which combine a personal narrative with a researched thesis and argument on the same topic and applied concretely to West Chester University. My students may be initially befuddled about how to organize this hybrid paper, so they appreciate the compact guidance of this single graphic.

Bio

B.G. Betz (she/her) teaches part-time in the English Department at West Chester University and focuses on guiding students with their writing and on giving presentations about women’s popular fiction. In her spare time, she reads and drinks tea, both voraciously, and searches for perfect sourdough bread and heirloom tomatoes.