Strangers Holding Space: An Online Carework Experiment between Pre-Tenure Writing Program Administrators

Ashanka Kumari and Sarah Riddick

Keywords: collaboration, academic productivity, TT pressures

Categories: Academic Pressures (or Critiques of Neoliberal Horseshit Productivity Expectations, as suggested by Amy Vidali); Building Community in Isolating Times

Introduction

This is a story about a carework experiment. We wondered how we—two tenure-track professors at widely different institutions and experiences but with similar positions—value (or don’t value) carework.

We, the authors of this piece, have never met in person and had only interacted once prior to coming together to collaborate on this project. In July 2021, the editors of this special issue reached out with a list of interested authors, encouraging us to independently connect with one another and to work on the pieces for this special issue. Ashanka saw Sarah’s name on the list of potential contributors with the keywords “pre-tenure, WPA work, gender, grief” and immediately wanted to reach out with similar topics in mind. Ashanka notes recalling the positive connection she felt when she and Sarah had a three-hour phone call a year prior, when Ashanka took over Sarah’s previous position as associate copy editor of enculturation: a journal of rhetoric, writing, and culture. Sarah responded with interest to Ashanka’s query about working together, and here we are today.

In our first of many conversations about this project—a little more than a month prior to the deadline for drafts—we found ourselves leaning on one another and commiserating about many things, like WPA work and pre-tenure life, but largely life in general and the endless grief, trauma, and many challenges we’ve felt in this COVID-work climate. Most of all, we reflected about how little we’ve had the comfort of sharing the human parts of ourselves in academia, an environment that historically models an automatonic approach to work wherein the personal remains rarely valued. We both needed space to heal.

Thus, we decided to pursue this as a “carework experiment” in which we would intentionally pay attention to those human moments. We chose to take the following month as a moment to document and check-in with one another each day and each week for accountability. Notably, we were holding each other accountable not for typical work (e.g., research and writing), but rather for carework. Our goal was to relearn how to take care of ourselves amidst our ongoing challenges; to get there, we experimented with self-carework and caring for each other. In what follows, we share some of this carework in action as we worked to feel safer as precarious professionals, to prioritize our health, and to challenge and unlearn academic values of productivity toward centering carework as priority.

Experimenting with Carework

We purposefully structured our carework experiment loosely, with the explicit goal that everything we did in this experiment should support us, not burden us. Broadly, this structure included the following (flexible) parameters:

-

Daily carework accountability check-ins with one another, with no expectation to respond to one another’s check-in

- Multimodal composing tools: mobile text messages

-

Weekly meetings with one another (2 hours/wk)

- Multimodal composing tools: Zoom, Discord, Google Drive

-

Daily notes on our own about our carework (10-30 min. daily)

- Multimodal composing tools: Day One, planners, verbal processing with our partners

This structure evolved throughout the month, beginning with our choice of multimodal composing tools. During our first meeting, Ashanka suggested that Sarah try using dictation to log her entries, as speaking aloud suits Sarah’s communication style. (There were many moments of, “Ooh, we should write that down!” as Sarah would verbally process in our meetings.) Later that day, Sarah suggested the Day One app to Ashanka as a possible tool for quickly logging entries, which might make this new project more feasible and enjoyable. We experimented in the first few days like this, and we quickly realized that we both preferred the Day One app, which offers a range of multimodal composing tools for journaling and documenting (e.g., photos, audio, freewriting) and suggested templates; these features felt more inviting than a blank page. Almost immediately, we each settled into logging our carework and reflections daily via Day One.

Second, the type of entries we logged evolved, and they constantly varied. Here, we offer some brief data about the kinds of entries we each cataloged over the month:

Ashanka: I made 25 total entries:

- 1 on Google Docs

-

24 DayOne entries

- 23 on mobile app

- 1 on iPad app

I (Ashanka) primarily used the built-in templates at the end of each day. It was rare for me to not use a template. Only 4 out of these 24 Day One entries don’t start from templates. I also wrote nearly every day and only missed two days toward the end of our 26 or so documentation days, when I had friends in town and was trying to stay off tech. The most used prompt for me was the “5 minute PM” template built into DayOne, which asked me to list “Three things that happened today” and write about “How I could have made today better.” I didn’t always answer that second question. I think what drew me to this particular prompt over and over was the simplicity (for me) to just note three things that happened. They didn’t need to be “good” or “bad” things, just things. There were always plenty more I could list, and only toward the last few days of our experiment period did I document more than three. For me, a recurring theme of “overwhelm” and desire for naps came up a lot. These have been immensely important recognition and rest moments. When I noted being overwhelmed, I wasn’t always specific about why, but I always found myself pausing and thinking about why, whether I wrote about it or not. Often, my feelings of overwhelm came from work and the large list of items before me; more often than not, I recognized that the expectations I set for myself weren’t realistic within the parameters of a given day. The other recurring theme was food/cooking/meals. I realize it’s super important for me to have my three meals a day, which I can’t do without and have scheduled in each day for years now. These are significant moments of carework for me, and my partner helps me remain accountable for this schedule, especially during the pandemic when we’ve eaten together nearly every day.

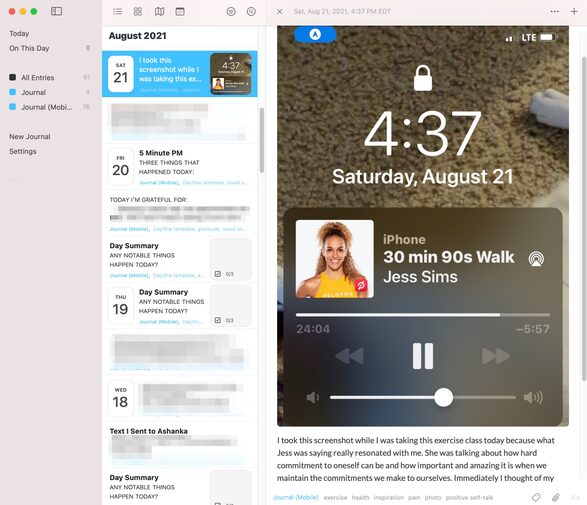

Sarah: I made 79 total entries:

-

Day One entries

- 74 on mobile app

- 5 on desktop app

- 1 voice-dictation to Microsoft Word

- 2 voice recordings

Several patterns emerged from these entries, which reflect how my approaches to multimodal composing about carework changed during the experiment. Initially, I experimented more broadly, as illustrated by the few entries I composed aloud or on my computer (i.e., 8 out of 79). Eager as I was to try different composing styles, I quickly felt burdened by this approach. Thankfully, Ashanka’s suggestion to try the Day One app templates alleviated this pressure. With this selection of simple, structured prompts, the words began to steadily flow. Soon, I shifted away from my narrower focus on daily carework into a wider range of writing about work in general—logging work I did, reflecting on it, evaluating it, processing it, acknowledging it. A surprising but happy finding is that my entries also shifted heavily from self-care lists and logs to deeper reflections and gratitude journaling. Although my daily focus (including in my writing) was still on carework, my initial “carework accountability” approach eventually gave way to more nuanced reflections on the growth, joy, and gratitude I was experiencing in relation to this work (see Fig. 4 in Appendix A). Unfortunately, as my entries’ tags indicate, the most frequent themes were often negative (e.g., “fatigue,” “burnout,” “stress,” “pain,” “guilt,” “pressure”); it does not escape me that the most frequent tag for me in this carework experiment was “productivity,” which intersects with all of the aforementioned tags. By contrast, more positive themes in my tags include the parts of my life that nourish me, such as “exercise,” “food,” “quality time,” and “loved ones.” Overall, these entries are already helping me recalibrate my daily life (including how I perceive it), and they are encouraging me to prioritize making time for my carework and wellbeing.

We did not end up adhering to this structure every day. Depending on the day, one or both of us may have been struggling with too few hours in the day and too many other commitments, or we may have needed to arrange our priorities in a different way than usual. For instance, for about three days in mid-August, each of us dedicated a little more time than usual to focus on the “life” aspect of “work/life balance” (i.e., quality time with loved ones). In the days that followed, Sarah’s academic year formally began. Her days immediately shifted into back-to-back meetings, WPA work, and student advising. Suddenly, the schedules and routines Sarah had created for herself, including her carework, were completely upended. On the first formal day of the academic year, Sarah shared in our meeting that she was struggling with how many times she’d had to delete blocked-out research time from her calendar in order to meet so many other demands on her time, after two months of successfully maintaining that boundary.

The end of the project for Sarah somewhat mirrors the first half of the project for Ashanka. Whereas Sarah had more time in late July/early August to prioritize research and carework, Ashanka was teaching a summer course at that time while transitioning into her new role as a WPA. Consequently, Ashanka was encountering substantial challenges each day with maintaining a work/life balance and managing different commitments and expectations for teaching, administration, and research work. During our second meeting, for instance, Ashanka sighed and said, “I’ve received 72 emails since this meeting began.” During our fourth meeting, the official first day of Sarah’s academic year, Sarah was singing a similar tune. Indeed, throughout all of our meetings, the notifications would continually roll in, exacerbating the pressure and stress we were trying to process and distance ourselves from.

Over the course of this experiment, Ashanka consistently needed to navigate an active academic term and everything that comes along with it while preparing for another term to come, whereas Sarah was transitioning into a new academic term. These work conditions are reflected in the data each of us produced day-to-day and week-to-week. For Ashanka, briefer lists and reflections helped her produce a steady amount of individual data across all four weeks. For Sarah, on the other hand, the first two weeks happened to also be her first window in years to focus on carework, and she used this opportunity to write longer reflections and to experiment more actively with her carework. In the second two weeks, however, her regular academic schedule resumed, and it became more challenging to invest this time and energy; thus, her entries became briefer, more straightforward, and less frequent.

We note these fluctuations and inconsistencies because they reflect three of the key themes we wrestled with in this project: rigor, productivity, and failure. Perhaps the best example of this process is how we addressed time-tracking. As Sarah remarked in our fourth meeting, “We are programmed to try to legitimize our day—every action we perform and every ounce of energy we expend—so that people who are evaluating us (including ourselves) will understand why we ‘failed’” in certain ways that day, that week, and so forth. As a new tenure-track WPA, Sarah has spent the past year creating her own daily data about this. Each day of the week, she blocks out the time she spends working in her Outlook calendar, which she color-codes by type of work (e.g., “Research,” “Teaching,” “[WPA] Admin,” “Service”); she keeps more detailed notes about the specific tasks in a variety of documents. Doing so has helped her identify when and where her time and energy is spent each week, and her calendar illustrates how many fluctuating obligations and conflicts routinely arise between her various roles (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 in Appendix A).

In our second meeting, we looked at a random sampling of previous weeks from Sarah’s calendar. We were immediately struck by how the occasional “blank” spaces seemed to visually signal a lack of productivity, which, in turn, produces feelings of guilt and failure. Yet, upon closer look, this time was productively, necessarily spent on other forms of work. One of the weeks Sarah randomly selected with Ashanka, for example, had a blank space in it on Monday from 3:30-6:00 pm, which looked like an outlier in productivity that needed justification. Yet, that blank space followed nearly eleven consecutive hours of nonstop work, beginning at 4:00 am. For those two hours, Sarah had reached her physical limit and needed rest, but then she resumed working at 6:00pm. As we continued analyzing these sample weeks, we discussed why these “blank” spaces—typically around 15-30 minutes—were occasionally present in a calendar that otherwise showed working seven days per week (e.g., making coffee, getting dressed, caring for a loved one or herself).

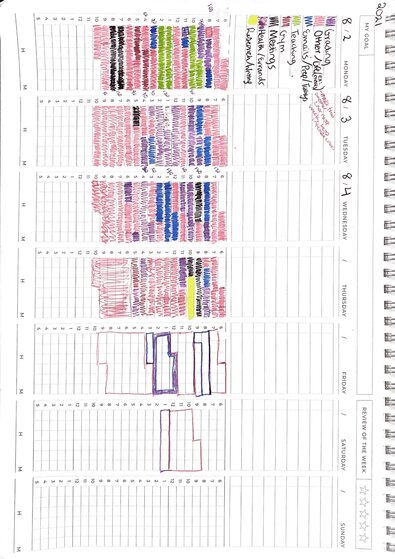

Following this meeting, Ashanka felt inspired to try her own version of color-coded time-tracking. For a few days, this worked well for Ashanka, and she excitedly showed Sarah what she had logged so far at the next meeting (see Fig. 3 in Appendix A). Yet, Ashanka realized soon after that the very questions and feelings we’d addressed while analyzing Sarah’s calendar were arising in her and were creating new feelings of guilt, pressure, and stress. Specifically, Ashanka noted feeling burdened by blank space and like she wasn’t working hard enough when the amount of rest/personal time logged exceeded her “work” hours. Ashanka recognizes deep down that the personal is necessary and well-justified, but due to the conditioning and pressure of academic work, especially pre-tenure, it hurt her mental health to think about her time this way. Thus, she moved on—something we each did regularly in the project when we realized that an approach was no longer serving our carework needs and goals.

Ultimately, our findings reflect the different work/life conditions we were each navigating that month, as well as how we actively responded to them to care for ourselves and each other. During the first half of the experiment—when Ashanka was navigating the end of a summer semester and the start of a fall semester—Sarah tended to initiate check-ins as an acknowledgment that she had more capacity to do so during those two weeks; this included trying out different approaches to check-ins to ensure these check-ins didn’t add further stress or pressure for Ashanka. Likewise, Ashanka held space for Sarah—who, amidst the pandemic, joined the tenure-track and began directing a degree-granting program—validating and encouraging her. In our meetings we worked, and we talked about WPA work (e.g., hiring adjuncts, staffing classes, answering emails, advising students, coordinating events, working with campus administration), research work (e.g., copy-editing for enculturation, current research practices and questions in Rhetoric & Writing Studies), and teaching (e.g., inclusive pedagogy, teaching in general and the pandemic). Yet, we also dedicated time in each meeting to listening and to supporting each other, smiling at one another’s animals, routinely celebrating naps and snacks and other seemingly small acts of self-carework and boundary-setting that helped us carry on.

By the month’s end, we had produced ample data, but more importantly, we had produced ample change in our thinking and towards our practice. We each (re)learned the importance and value of boundary-setting, support systems, rest, and the space we hold for one another. But this work is not over.

Reflecting on Our Experiment

Ultimately, we’re left with these questions as we move into another COVID-climate semester filled with continued uncertainty: How do we keep carework at the center? How do we keep this valuable focus on ourselves? We close with some reflections in response to these questions.

Sarah: Early on, I recognized that one of my biggest hurdles in the experiment was allowing myself to reevaluate conventional expectations for what qualifies as rigorous and productive research and, by extension, what qualifies as valuable work. Although this is a challenge I embraced and enjoyed, it is and continues to be a challenge insofar as I am continually challenging years of cultural and professional conditioning. Throughout the month, thoughts would form along the lines of, “Will there be enough data?” “Will there be good enough data?” “If something goes ‘wrong’ today, and one or both of us can’t maintain our schedule, will the data be compromised?” As these thoughts formed, I would remind myself of what I’d said at the outset: “No matter what happens, this project about carework will have been meaningful, valuable, and productive because we will have dedicated consistent time and energy to caring for ourselves and others.” As our experiment comes to a close, I mean this statement even more.

During our first week, I wasn't feeling great. I was swimming in stress about everything on my plate right now, everything I wanted to accomplish, everything the upcoming year would bring. More than that, I was feeling burned out, despite so many efforts this summer to recover from that. Speaking with Ashanka for the first time in a year (i.e., our first meeting) was lovely but difficult for me; the past few years have been defined by different kinds of pain, and I’ve been struggling to move forward from it. Ashanka held space for me as I shared that pain with her, and by the end of our meeting, I felt a positive shift in myself. I left our first meeting feeling energized and excited, and I was buzzing to get started on the project.

Soon, though, the same feelings began to return. By evening, I hadn't logged anything, and I felt resistance about “having to” write at the end of the day, when it would have been so much easier to just do my nightly exercise and then wind-down. But I did it; I wrote a brief entry, and I put a mental check in that box. The next few days, that resistance was still there. Writing about carework felt like an(other) obligation, a tiring chore to meet the small, open-ended commitment of jotting down something reflective about my day and how I took care of myself. That says a lot about where things stand with self-carework lately, no?

Fortunately, I started noticing other moments each day in which I was being kinder to myself and gentler with how I assessed my feelings, thoughts, actions, and accomplishments. Because our project is so open in terms of its parameters and approaches, and because its overarching goal is to help us care better (for ourselves and for others), the worries I had about what I was recording or writing each day (Is this good enough? Will it fit in with what Ashanka is doing? Will anyone value this?) began to give way. I became empowered by the fact that I could chart my own daily path through the project, that it was okay to try out lists on one day and to write reflections on another. I started having fun thinking about new approaches to carework (for myself and for Ashanka), and it delighted me that these changes could count as meaningful experimentation. By the time I met with Ashanka for our second meeting, I probably seemed like an entirely different person. I smiled, it seemed, nearly constantly in that second meeting.

Importantly, I asked Ashanka about my ideas for experimenting with carework, and I communicated upfront that she was not obligated to reciprocate this effort; again, the work we do should help, not burden, each other. For instance, I initially approached my daily check-in texts with Ashanka in a similar way to how I check in with friends about writing goals (e.g., "Wrote 500 words today! How are you doing?"). Each day, I’d send Ashanka a brief text, in which I’d offer a quick highlight of my carework, and then I'd ask about hers. We'd typically talk a bit back and forth, but I'd also try to keep the exchange short so that she didn't feel obligated to keep engaging. Toward the end of the first week, I wondered if perhaps that approach needed an update. Announcing my own self-care upfront might be centering myself when a more caring gesture might be to begin by checking in about her day. So, I tried that out, and I asked Ashanka in our second meeting if any of these approaches were working for her. I explained all of the above, and I said I'd be happy to adjust anything. Happily, she liked our daily check-ins as they are, so we decided to continue with them as-is. Still, I like the "challenge" of finding new ways to extend care to her in the future.

Besides the fact that I am feeling more present in and appreciative of my smaller moments in everyday life—thanks to the active reflective and self-caring work I've been doing throughout the past month—I feel so grateful to be connecting in these ways with Ashanka. I firmly believe this project was time and energy well spent because we cared for ourselves and each other. We're developing what seems to be a rare bond in our line of work in this experiment. Although this project and our efforts in it are perhaps not sustainable to this extent, I hope we can find ways to continue this work moving forward, and I encourage others to try it with us.

Ashanka: I’m a human who has diagnosed anxiety and depression, and I work with these aspects of my being every day. One thing that remains important for me is scheduling and keeping routines, many of which COVID-19 ruined or required me to revise. A recurring theme in my documenting of carework each week, that I haven’t mentioned until this part in our writing, was reflecting on weekly therapy appointments. Through both my conversations with Sarah and in therapy, I have learned that so much of my response to work, to the concept of “productivity,” and to what I value and perceive others value comes from practices ingrained since childhood. In school, for instance, we’ve been taught to focus on completing assignments, on meeting certain marks to obtain certain goals, and to prioritize work over our health. I can count on one hand the number of times an authority figure or mentor told me to prioritize rest or my health. This number increases each year as the conversation around mental health gets further amplified, but it’s still a task that often becomes an afterthought.

For me, this experiment with Sarah helped me reflect a lot on my actions as a person, while setting the stage for a big transition for me: stepping into the role of Director of Writing (WPA) at my institution in July at the same time we engaged in our experiment. I found myself echoing “prioritize your health first” across all of the writing program training sessions I held for our teachers. And I stand by that and plan to continue to do so as I proceed as an academic. I think a lot of the change we desire has to start with our own actions to change the spaces we’re in. Moving forward, I wonder how we can continue to challenge academia, our spaces, our cultures to remember how insignificant work is in the grand scheme of things if our emotional, mental, and physical health are compromised. No job or career path is worth that sacrifice, frankly.

I learned a lot from Sarah through our weekly accountability, a practice I hope to continue to carry with others as it’s always the most significant way to remain accountable to myself. During our experiment, it was helpful to know that I wasn’t alone and other academic minds were also thinking critically about carework, such as Sarah and those working on pieces for this special issue. It’s going to be harder as the Fall 2021 semester picks up, but I plan to keep weekly check-ins going with accountability partners including virtual writing groups, my therapist, my partner, and Sarah. We must amplify carework as much as we do other aspects of our research, teaching, administration, and service lives in academia. And we must stop apologizing for carework.

Appendix A

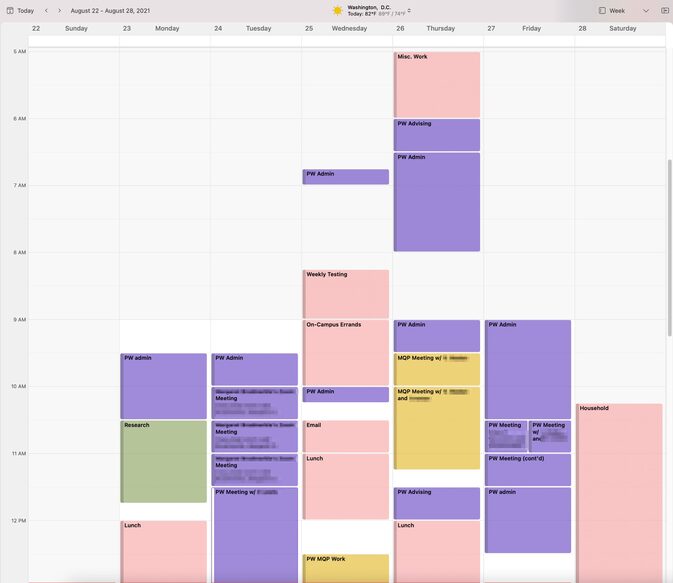

Figure 1. Screenshot of Sarah’s Outlook calendar between August 22 to August 28, 2021, the first week of the fall 2022 semester. Calendar shows various activities and types of work that took place throughout the week between 5am to 1pm (i.e., first half of the day). Activities and work are color-coded by category: purple for writing program administration; yellow for teaching; green for research; light pink for miscellaneous (e.g., lunch, email, household). Screenshot shows a large amount of purple (i.e., WPA work) during this time period.

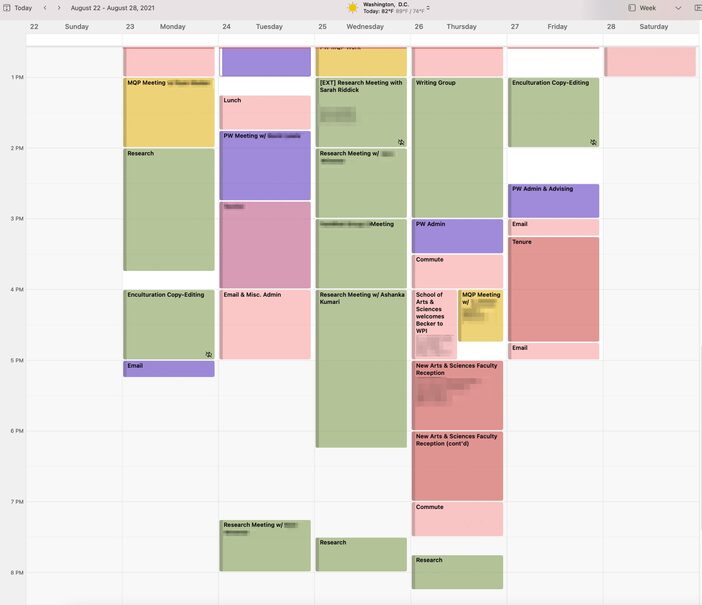

Figure 2. Screenshot of Sarah’s Outlook calendar between August 22 to August 28, 2021. Calendar shows various activities and types of work that took place throughout the week between 12:30pm to 8:30pm (i.e., second half of the day). Activities and work are color-coded by category: purple for writing program administration; yellow for teaching; green for research; light pink for miscellaneous; red for faculty events and tenure-related work (e.g., updating dossier). Screenshot shows a broader mixture of activities and work, with lots of green (i.e., research).

Figure 3. Scan of Ashanka’s logged work hours between August 2 to 8, 2021.

Figure 4. Screenshot of Sarah’s desktop Day One app. Screenshot shows a vertical, chronological list of entries on the left, and a screenshot of Sarah’s mobile phone homescreen. The homescreen screenshot shows the time (4:37pm) and date (Saturday, August 21) in white text and a paused “30 min 90s walk” exercise class with instructor Jess Sims. Below the screenshot, Sarah wrote, “I took this screenshot while I was taking this exercise class today because what Jess was saying really resonated with me. She was talking about how hard commitment to oneself can be and how important and amazing it is when we maintain the commitments we make to ourselves. Immediately I thought of my [. . .].

Bio

Ashanka Kumari is Director of Writing and an Assistant Professor of English, Composition and Rhetoric at Texas A&M University – Commerce where she mentors, researches, and teaches graduate and undergraduate students in topics including composition theory, antiracist pedagogies, nonfiction and professional writing, and multimodal composing. Her work has appeared in WPA Journal, Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, Composition Studies, and the Journal of Popular Culture, among other journals and edited collections.

Sarah Riddick is Director of Professional Writing and an Assistant Professor of Professional Communication at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, where she researches and teaches multimodal rhetoric and writing, digital publics, social media, rhetorical theory, and professional writing. Her work appears and/or is forthcoming in Computers and Composition and Rhetoric Review, among other journals and edited collections.