Q: Am I All Right? Am I Not All Right? A: Both/And

Jennifer Marlow

Keywords: childcare, process journal, blog

Categories: Parenting and Possibility in Impossible Times; (De)Constructing Writing; Queer Responses to the Apocalypse

I thought I was nailing the pandemic until I saw my therapist's face on-screen via Microsoft Meet on May 20th, 2020. After all, my family was among the lucky: a two-mom household with one easy-going preschooler, both of us still employed and with my wife only having to report to work in-person 2-3 days per week. I spent the last two weeks of March and much of April putting in as many hours as possible on the days when my wife was home and then working both Saturdays and Sundays to make up for the days during the week that I spent with my son trying to replicate the stations he had at his preschool: literacy, art, building, drama, math, science. My SMS feeds filled up with pandemic pedagogy strategies and science experiments for young kids. I printed out worksheets, made magnets, drew clocks, filled a learning jar, and created explosions in the kitchen. Weekends, we hiked as a family, taking lots of selfies. Our dog was in doggie heaven here on earth. It seemed idyllic and calm and surprisingly not rushed—an unfamiliar but welcome feeling. As I captured our days in photo and video on my iPhone, I fancied us as a kind of pandemic poster-family.

Figure 1: Getting it done: My wife taking work phone calls with a five-year-old on her shoulder.

Only a few weeks before March 13th, 2020, I had written in my journal:

I just want one morning where I’m not rushing out the door with my head spinning. Just one quiet, peaceful morning with nowhere to go/be.

On March 16th, while my son sat in front of a screen, I rushed around the house trying to recreate his preschool setting. I categorized things in bins, made signage, dragged toys he hadn’t played with in awhile up out of the basement, copied schedules off the Internet and adapted them to what I hoped might fit our new life. That afternoon, I put him back in front of the screen and hopped on Zoom to meet with my students, whom I had last seen as we left class the week before, swapping playful banter about what might happen if this newsworthy pandemic hit our area of the U.S. So naive were we then.

The first thing to be back-burnered in this new life, of course, was writing. From March 11th, 2020 to March 31st, 2020, I did not do any writing aside from emails and text messages. Typically, I keep a writing process journal, as recommended by Louise DeSalvo in her book, The Art of Slow Writing: Reflections on Time Craft and Creativity (DeSalvo borrows the idea from novelist Sue Grafton): “Our process journals are where we engage in the nonjudgmental, reflective witnessing of our work. Here, we work at defining ourselves as active, engaged, responsible, patient writers” (2014, p. 70). It is essentially the documentation of a writer’s work, the trail of breadcrumbs that we leave ourselves to remember where our writing projects have been and are going. I have kept one since July of 2019.

My writing process journal from March 31st, 2020 reads:

So much has happened (and not happened) since that last entry three weeks ago. I haven’t been writing, as I’ve struggled to get life in some kind of order since its disruption by the global Coronavirus pandemic. Of course I’ve been wanting to write about the experience of the pandemic, but everyone else is already doing that. . . what more can I possibly add? In what better way could I possibly state this strange, surreal experience that we are all sharing, though in different ways? And so, I just haven’t even tried. Scared to fail.

Later in that same entry, I try to figure out what writing could look like for me in the time of Covid:

But now is the time to re-prioritize my writing goals, as I have had to re-prioritize everything else—especially in my work life. Now is the time to do the things we love, the things that make us feel good, because the good moments are punctuated by stories of lives lost and irrevocably changed by this illness. The good moments are punctuated by intense fear that I or one of my family members will catch this illness. The good moments are punctuated by obsession over how to obtain goods and services (especially food, but other items as well) safely or at all when many things are unavailable (my current needs/wants/obsessions that are impossible to get are hydrogen peroxide and paper towels).

The next day’s entry reflects again my struggle with putting into words what was happening:

Getting myself to actually hit the page these days is tremendously difficult. I still lack direction, and I’m filled with fear that all of the things I’m feeling and experiencing in these strange days will not be captured with language. In fact, I know they won’t and can’t, so really that shouldn’t stop me, and after all, I feel so much better when the words are out—in whatever form.

I would often go back and read that journal entry in which I wished for one day of not rushing out the door. I kept my focus on how every morning now was unrushed. I had gotten my wish ten-fold. I didn’t think—only to think we were succeeding wildly at this pandemic lifestyle. I spent my days taking inventory of my privilege, worrying about the frontline workers who also had children, many of whom no longer had childcare. We were so lucky, I kept saying. As two introverted homebodies, I felt we were cut out for pandemic life so much more than many of our extroverted friends who were passionate about travel and doing things outside the house. So why then did I instantly burst into tears on that early Wednesday morning, when my therapist’s face showed up on my computer, asking me how I was doing?

Because seeing her face made me stop. I hadn’t stopped. My brain hadn’t been quiet. It was like hitting a brick wall in the middle of a seemingly successful marathon run and suddenly becoming aware of the fact that you have body chills and pee running down your leg. As I struggled with how to put the effects of the pandemic into words and feeling like language was inadequate, I was, therefore, in many ways still avoiding thinking through the pandemic. By not putting it on the page, I was continuing to trick myself into believing that I was fine when I wasn’t.

During the days I hadn’t really had time to think, so focused was I on our multicolored schedule, filling out our plans on the morning whiteboard and trying to keep life moving forward in some version of “normal,” but nights I would lie awake with dread over one of us or another family member contracting the virus. I’ve suffered from anxiety since childhood, but Covid only intensified my nighttime restlessness. Each day when my son would wake up, I would try, discreetly, to feel his forehead and cheeks. I would stare at him making mental calculations and assessments: did his eyes look droopy, was his face flushed, was he logy.

Ultimately, I let myself just write about Covid in any medium, in any form. After all, the only way out is through. What did my multimodal composing look like in those first few months of this global pandemic? It looked like posting to the “mommy blog” that I had started when Levi was born. It looked like Facebook posts documenting my family’s pandemic life. It looked like links to articles that resonated for me and the comments threads that followed. It looked like texts to my parents sharing pictures and videos of the parts of their grandson’s life that they were now missing. It was documentation of a life that probably looked in many ways similar to the lives of others like me: middle class, highly educated, white, still employed, and therefore it was also documentation of a life that looked drastically different from those who were separated from me by skin color, income, and education. But as Chloe I. Cooney (2020) put it in her popular Medium post, “The Parents are Not All Right,” “[I]t’s precisely the privilege of this vantage point that in a way makes it so stark. This is the best-case scenario?”

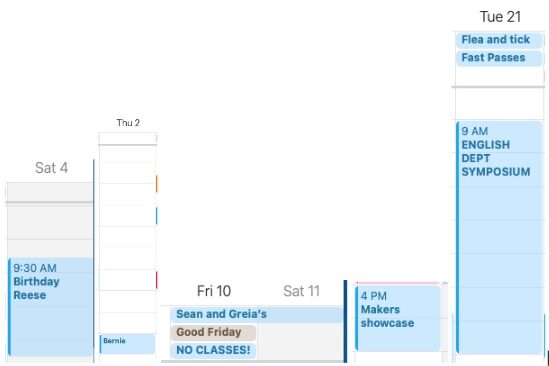

Uncertainty took over our lives. Would CCCC be held? Would I travel if it were? We were still going to be able to go to Disney in May, right? Even now, the events that had been previously scheduled for those early months of the pandemic remain on my calendar. I couldn't bring myself to remove them, as I was stuck harboring a secret and ludicrous hope that this would all go away.

Figure 2: Image of digital calendar. Blue boxes contain scheduled events such as parties, trips to visit family, and celebrations of student work.

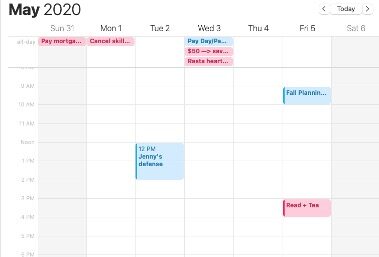

But eventually my calendar started to look more like this—a smattering of online only events:

Figure 3: Image of digital calendar now almost empty. Colored boxes represent online-only events like a friend’s dissertation defense and an online meeting.

I left the house only for groceries every other week, double-masked and wearing gloves, slathering myself in hand sanitizer at the end.

By early April, I describe, in my writing process journal, trying to find ways to make it easier on myself. I read all the pandemic articles describing the ways in which people were seizing upon their new abundance of time and starting all kinds of home improvement projects, hiking high peaks, baking bread, taking up new hobbies, etc. Then I read all the pandemic articles pushing back against this capitalist-driven mentality of constant production and consumption. These articles recommended staying inside, resting more, and bingeing Netflix series.

[B]ut the reality is, neither of those ideas are available in my life. I’m a mom who is also trying to work full-time from home. I am, in some ways, busier than ever.

The irony was not lost on me that my multimodal composing at that time was built around the pictures and videos that I took of our pandemic life, and those images and media clips made it appear that things were quite lovely—that I was, in fact, all right.

From my blog at the end of April 2020:

-----

Aside from the occasional lighthearted mention of Levi crashing a zoom meeting or a quick meme about interrupted work time, my bulleted lists detailing our lives are filled with things like long walks, bike rides, yummy food (making and eating), kite flying, driveway chalk, puzzles, and legos. And it’s true, in many ways I am so grateful for this unexpected and unprecedented time with my little family. But as we all know, Facebook tends to showcase the delightful moments, the orchestrated ones, the ones we want to remember.

I cannot really photograph indigestion and nights lying awake with anxiety. I don’t capture the all too many moments that I lose patience with Levi because I’m thinking about work (or trying to work), or because I’m still on a tight operating schedule (because I need to work) and he isn’t cooperating with my agenda. How do I capture the fact that I haven’t had a weekend morning where I haven’t worked in over a month?

-----

It was, however, only when I made myself begin trying to put that time period into words that I could get at the nuance, at the fraught both/and nature of what I was experiencing. It was beautiful, and it was hard. I was both succeeding and crying to my therapist over the costs of that success. What was hard for me was hard for many other caregivers and even harder for those caregivers in more dire predicaments. And yet, there was also this (from my April 15, 2020 blog post):

-----

I recently asked this question via a Facebook post: What will you miss most when this is all over? (I’m using “all over” loosely here). The responses ranged from silly to serious, but they were all quite telling, and they all held a sense of beauty and hope.

Some highlights:

- Being together as a family 24/7, despite them driving me nuts occasionally.

- The clothes I was able to wear before all of this started. Stress eating is a bitch.

- The shift in perspective and priorities. The need to be creative with our meals, time, activities, and finances. The community cooperation and global connection. The clarity of knowing what’s most important. The simplicity of more limited choices.

- The sense of “community” that we are currently experiencing.

- Having two parents home….

- My retirement account.

- Seeing practically every human on our planet focused on the same problem. I hate that it takes a pandemic like this, but imagine if we were all united in fixing other problems…

- Sleeping in.

- Unhurried everything.

- The cleaner environment that’s occurring due to COVID-19 stopping the destruction caused by capitalism in its tracks.

Hard/beautiful.

References

Cooney, Chloe I. (2020, Apr 5). “The Parents Are Not All Right.” Medium. Retrieved from https://gen.medium.com/parents-are-not-ok-66ab2a3e42d9

DeSalvo, L. (2014). The art of slow writing: Reflections on time, craft, and creativity. St. Martin's Griffin.

Bio

Jennifer Marlow is a Professor of English at The College of Saint Rose in Albany, NY. She teaches courses in composition, creative nonfiction, and digital media. Her research interests include educational technology and digital pedagogies for the writing classroom, hybrid forms of prose writing, and labor practices in higher education. Her work is published in Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy and Forum. Her co-authored eBook, Are We There Yet?—Computers and the Teaching of Writing in American Higher Education—Twenty Years Later was published in 2021 by Computers and Composition Digital Press. She co-produced/directed the documentary film, Con Job: Stories of Adjunct and Contingent Labor. Her poetry is published in Paterson Literary Review, Meteor Shower Over the City of God and Other Poems, and Voices of Michigan.