Writing as Carework: Healing My Writing, Healing Myself

Beth Buyserie

Keywords: writing anxiety, healing, sexuality

Categories: Queer Intimacies and Radical Kinship During Isolation; Disability, Illness, and Survival (When the World Doesn’t Want You To)

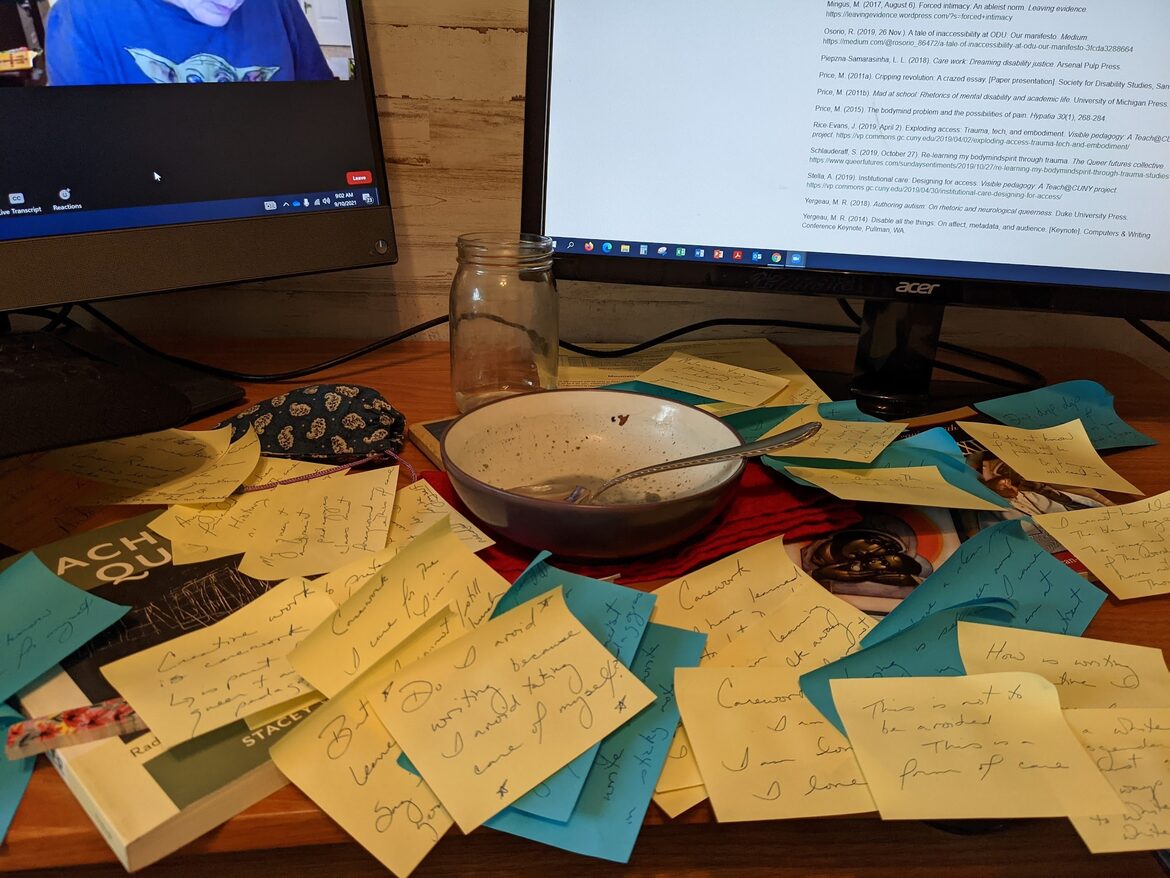

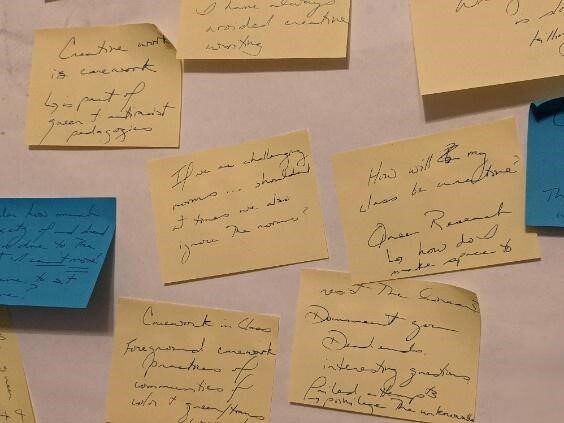

| Image 1: Photograph of the beginning of my writing process for this essay. Yellow and blue sticky notes, covered with my cursive handwriting, are scattered across my desk. On each note is a fragment of this essay. In the center of the desk is an empty purple cereal bowl, a silver-colored spoon, and a clear mason jar: the remnants of the breakfast I ate while writing. Peaking out from under the sticky notes is a copy of Stacey Waite's Teaching Queer and several Catholic prayer books, given to me by my dear friend, L Heidenreich, who is a scholar of queer Chicanx histories. They and I have a weekly writing time over Zoom. On the desk are two computer screens, though the photo cuts of the top of each screen. On the left screen, L's chin and shoulders are visible. They are wearing a blue t-shirt with an image of Baby Yoda, whose head and ears just peek onto the screen. On the right screen is the works cited page from the essay #Triggered" (Rice-Evans and Stella, 2021), which inspired me to compose an essay with photos. |

I am trying to learn how to take care of myself. I have never written so well as when I wrote on sticky notes, when I had the permission from editors to not write a lengthy, traditionally academic essay. The call for proposals on Carework encouraged me to connect writing with caring for myself.

I have rarely excelled at caring for myself. As the oldest of 7 children, I took care of my siblings while my mother struggled against the cancer that would eventually overcome her. I have been a teacher and writing program administrator (WPA) my entire professional career, a job for which I have always sacrificed myself so that I can care for the students and teachers who mean so much to me. I have two inquisitive children, who shockingly insist on being cared for rather frequently. As I cared for everyone other than myself, my mental health suffered, slowly at first and then in earnest once I added being a half-time Ph.D. student in Cultural Studies onto my full-time WPA position.

At that same time period, in my mid-30s, my sexuality shifted. Writing and reading about queer theory became additionally painful at a time when I thought that I needed to continue to sacrifice who I was becoming to continue taking care of those around me. Thoughts of leaving the planet, my words for what was impossible to express in more clinical terms, were constant for a time. And writing, being faced with the complete unknown of the blank page, enhanced those feelings (and still does to varying degrees). Why? Because I had to write about my changing identity. To process the shifting story of my life through writing.

I have forgiven myself for that part of my past, for thinking it was more important to continue on the life path I thought was planned while wanting so desperately to identify and live as queer. It turns out fluidity and change are the fabric of life, and I am calmer when I weave my life in fragments rather than seek a solidified whole. In the introduction to their book, Nepantla2, L Heidenreich writes, “Nepantla is an ancient philosophy that views the world through motion-change, insisting that rather than a great chain of being, or survival of the fittest, the world is a great cloth—wove through energy. The creative energy is made manifest in both positive and negative ways—energy, events, and happenings pushing and pulling in and out of each other like the warp and weft of a great loom” (2020, p. xvii).

I was reading this introduction to Nepantla2 because the book’s author, my dear friend L, was the first person I came out to five years ago at a retreat for our church. When I moved away to start a tenure-track job, L and I began a remote writing time to ensure that we both keep writing, which so often has been the last thing that I wanted to do. But I know now that our time together is more than time to write: it is time to take care of ourselves and each other. L, who teaches queer Chicanx histories, always shares with me the creative writing projects that their students compose in their history classes. And though I have taught multimodal projects before, I never associated these projects with carework.

This essay, an invitation by the editors to keep writing, to keep taking care of ourselves, is my attempt at carework, to reframe writing as an act of care rather than one of sorrow.

Why do I avoid writing?

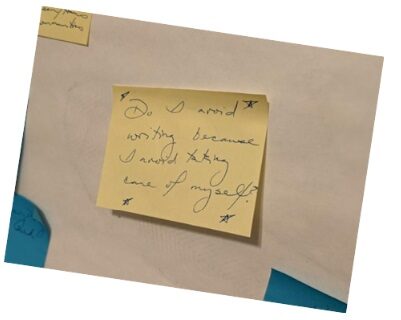

| Image 2: Photo of a yellow sticky note, on which I wrote the words, "Do I avoid writing because I avoid taking care of myself?" Four stars are scribbled, one in each corner. |

I have always associated writing with deep anxiety and depression. After 15 years of being a proud contingent faculty member and WPA, I am now on the tenure-track. I must write to survive. Yet writing threatens my survival.

I had a student several years ago who also had deep anxieties about writing, fears so strong that she could not produce even short drafts, despite her passion for the topic she could easily discuss in class, in spite of her beautiful insights on the subject. We tried multiple methods to help her overcome her anxieties with writing, anxieties that I could relate with all too well. But she eventually became one of the students who drifts away from class. How was writing a form of care for her? For other students like her? How can I teach writing in ways that are a form of carework . . . especially when writing causes or inspires the destruction?

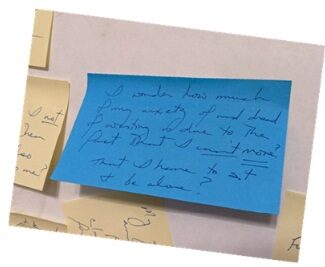

I desperately want to find the answer to this question for my students, but the answer is complex. My lived experiences help me understand how complicated the answer can be. I have been searching for the answer for over 20 years. As I sort out my own complexities and contradictions with writing, I am trying to answer this question in small ways, beginning with myself. While I have advised students to try the common “just keep writing” method, the “hot pen” approach that can inspire and produce fragments of insights, that process often induced more anxiety for me—particularly when I tried the method while sitting alone to write. It turns out writing “I don’t know what to write” when your job is constantly on the line is not stress-reducing. Typing on the computer always reinforced that I was supposed to create a finished product, and I would freeze when my words did not sound scholarly, despite all I know about revision being a process. Writing for tenure—particularly writing during Covid—enhanced the feelings of depression and inadequacy. To “succeed” in my job, I had to sit still with only my fingers moving. I had to be alone.

| Image 3: A photo of a blue sticky note. Written in my handwriting are the words, "I wonder how much of my anxiety of and dread of writing is due to the fact that I can't move? That I have to sit and be alone?" The photo is tilted, to suggest a sticky note stuck at random on a wall. |

In writing this essay, I tried new (for me) methods of dealing with my writing-connected anxiety. I have never considered myself a multimodal scholar, and while I have assigned multimodal projects, I always relied on the creativity of the students to enact the final project. Yet creating a multimodal document, a genre that is relatively new for me in essay writing, was key to managing my anxiety and to keep writing.

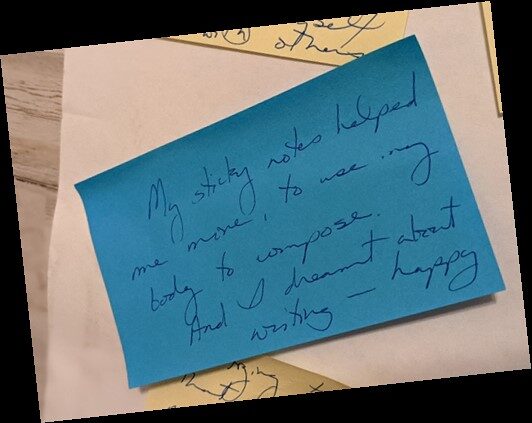

I began by writing ideas on sticky notes. I understand that this approach is not in itself a particularly innovative pedagogy, yet it did much to manage my anxiety. These “blank pages” were small and colorful, far less intimidating than a blank document. The admonition to keep writing finally made sense as I could write short phrases and fragments, and then rip one note after another from the pad to scatter randomly on my desk. Movement, it seemed, was key. Multimodality, at least for me, requires the kinesthetic. I wrote, with L and Baby Yoda writing alongside me on my computer screen, for a solid hour without stopping or judging my own thoughts. This process was Draft 1.

In my typical essay writing process, Draft 1 is never a relief. Of course, a first draft should be freeing: I no longer have a blank page. But the thought of having to take that mess of words and create them into something coherent never abated my panic. Yet this time, the process was different: I could learn kinesthetically. I scooped up all my sticky notes and arranged them—not in a linear order, but in clusters of ideas—on a large piece of paper. This was Draft 2.

| Image 4: Photograph of a large piece of paper taped to my office wall. On the paper are yellow and blue sticky notes on which I have written snippets of this essay. Some of the sticky notes have fallen to the floor, representing how slippery and fluid and at times unsustainable the writing process is for me. The photo is tilted, representing the angle of some of the sticky notes. Hanging on the wall next to the poster is a multimedia collage that I created for a graduate course on Critical Race Theory, taught by Dr. Paula Groves Price. In the comer, a 2-drawer wooden filing cabinet holds a potted green fern, a pride flag (and behind, less visible, a bisexual pride flag), and a canvas collage created by my goddaughter, who wishes I would move back to be near her. |

For Draft 3, I took pictures of these sticky notes and uploaded them to my blank document. I realized after I did this—a move which is uber-tech for me, the perpetual luddite—that I was for the first time not starting with the blank page. I had pictures, which were so much more comforting than disembodied text. I began to write.

When the all-too familiar writing panic started to set in during the actual writing, I had smaller tasks to accomplish: I could write a caption for a photo, I could play around with the location of each image on the page, I could write a shorter paragraph, a fragment. These small writing tasks, easily manageable and infused with a sense of play, allowed me to keep writing. I have often woken up in the middle of the night, unable to breathe, with the dread that I still had to write. I still feel a sense of peace remembering the morning I woke up having dreamt about this essay: about moving my sticky notes around, playing with their arrangement, wanting to write more on the bright little rectangles.

| Image 5: Photo of a blue sticky note with these words written in my cursive handwriting: "My sticky notes helped me move, to use my body to compose. And I dreamt about writing happy." |

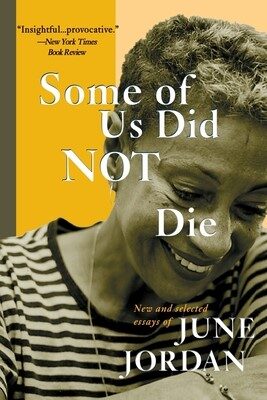

As I was writing on my sticky notes, I also started writing ideas for a graduate class I will teach next year on queer and antiracist pedagogies. I hadn’t planned to prep while writing this essay, but the two events connected themselves in my brain. The queer theory class I had taken as a grad student had been exceptional, but heavily academic—which ironically kept the questioning of my sexuality at bay, since I was rarely asked to personally reflect on my own heteronormativity, even as my mental health began to drastically decline due to my internal struggles. The course I took on Critical Race Theory had both challenged me academically and asked me to negotiate my identity as a white woman who cared about antiracist work while acknowledging my entanglements in white supremacy. That course had also assigned several multimodal projects that encouraged creative and embodied learning.

Both classes, so different in their approaches, enacted a pedagogy of care. Reflecting back, I think about carework’s role in queer antiracist pedagogies. And for the first time, inspired by my friend L, I thought about how creative work is also carework. How essential joy and creativity are to writing. To queer and antiracist pedagogies. To life.

| Image 6: Scattering of yellow and blue sticky notes that allowed me to start brainstorming a graduate class on queer and antiracist pedagogies. The notes jot down ideas for creative carework as part of these critical pedagogies. |

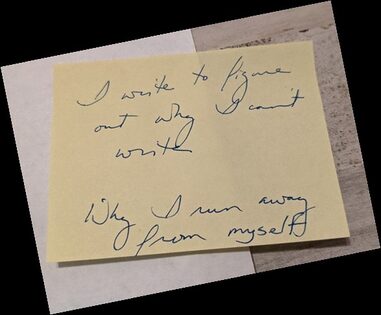

The last major essay I wrote, one that I deeply cared about, one where I connected reading myself queer later in life with bisexual literacies (Buyserie, 2022), again brought thoughts of leaving the planet. Sadly, that is not an exaggeration. Despite the journal editors’ kind encouragement to revise after a rather harsh peer review, I wanted to drop the project. To give up on myself. I had been laughed at once by someone in the queer community for coming out to them as bisexual, and I did not know how I could publicly write about my trauma. I wrote about how my first reading experiences on bisexuality reiterated judgment and exclusion from queer communities (Yoshino). In writing this essay, however, an essay inspired by fragments and little snippets of life, I found these words on bisexuality from June Jordan:

Bisexuality means I am free and I am as likely to want to love a woman as I am likely to want and to love a man, and what about that? Isn’t that what freedom implies? If you are free, you are not predictable and you are not controllable. To my mind, that is the keenly positive, politicizing significance of bisexual affirmation: To insist upon complexity, to insist upon the equal validity of all the components of social/sexual complexity. (Jordan 1998, p. 193)

It is too late to include these lovely and life-affirming words from Jordan in my previous essay, but I am thankful to write them here. They have given me life.

Why do I write? How does writing allow me to care for myself? And for not just myself but others?

| Image 7: Book cover of June Jordan's Some of Us Did Not Die |

| Image 8: Photo of a yellow sticky note, upon which I wrote, "I write to figure out why I can't write. Why I run away from myself." |

Writing this essay in this method has been freeing. While some might interpret writing an essay on sticky notes to be less than scholarly, I am grateful for the opportunity to begin to heal, at least with this one project.

I do not presume that I am “cured.” Indeed, like many disability scholars, I question the notion that cure is fully desirable (Clare, 2017). Writing, I expect, will still be painful. I still fear the blank page, the structure, the inherent judgment and rejection that academia prides itself on.

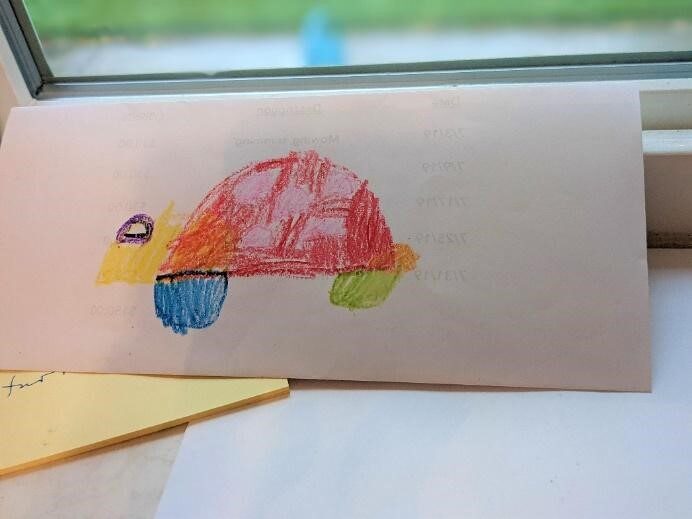

Yet I have, for the first time in so long, loved writing. This essay took care of me.

It brought me joy.

|

| Image 9: A picture of a multicolored turtle that my 9-year-old son drew for me using crayons. Turtles, thanks to J. Jack Halberstam, always remind me of the joys of being a queer parent (Halberstam, 2012, pp. 17-19). |

|

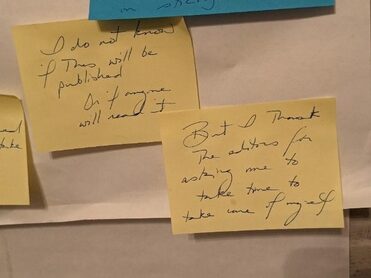

| Image 10: Photo of two yellow sticky notes with words written in blue ink. On the first note: "I do not know if this will be published. Or if anyone will read it." On the second note: "But I thank the editors for asking me to take time to take care of myself." |

I almost always cry when I write. Tears that leave me empty and hollow. I did not cry as I wrote this essay (well, okay, I did, but just once). I know I cannot always publish essays about sticky notes. But perhaps I can use creative, multimodal, and kinesthetic processes to write my way into healing.

To heal my relationship with writing.

To heal myself.

References

Buyserie, B. (2022). Reading yourself queer later in life: Bisexual literacies, temporal fluidity, and the teaching of composition. Literacy in Composition Studies, 9(2), 28-47.

Clare, E. (2017). Brilliant imperfections: Grappling with cure. Duke University Press.

Halberstam, J. J. (2012). Gaga feminism: Sex, gender, and the end of normal. Beacon Press.

Heidenreich, L. (2020). Nepantla2: Transgender mestiz@ histories in times of global shift. University of Nebraska Press.

Jordan, J. (1998). Affirmative acts: Political essays. Anchor Books.

Rice-Evans, J., & Stella, A. (2021). #Triggered: The invisible labor of traumatized doctoral students. The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, 5(1). http://journalofmultimodalrhetorics.com/5-1-issue-rice-evans-and-stella

Waite, S. (2017). Teaching queer: Radical possibilities for writing and knowing. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Yoshino, K. (2000). The epistemic contract of bisexual erasure. Stanford Law Review, 52(2), 353-461.

Bio

Beth Buyserie is the Director of Composition and Assistant Professor of English at Utah State University. Her work focuses on writing program administration, the teaching of composition, critical pedagogies, professional learning, and the intersections of language, knowledge, and power through the lenses of queer theory and critical race theory.