Come Out and Dance

Jolivette Mecenas

Keywords: queer families, queers of color, gun violence, graphic narrative

Categories: Queer Intimacies and Radical Kinship During Isolation; Visual, Sonic, Tactile, Interactive Texts as Self- and Collective Care; BIPOC Perspectives on Labor and Love during COVID

Content warning: gun violence

That second pandemic spring, my partner was teaching online from home, while I was in a tent on my campus, teaching in hyflex mode to the handful of masked students sitting in front of me, and to the black boxes on my laptop screen, their sporadic chat posts like faint pulse readings. Meanwhile, our 9-year-old son was not doing well on Zoom school. A year into it, he desperately missed other kids. Then we discovered that he was watching harmful videos during class time. My fault – I fumbled parental controls. The 9-year-old needed more care. I squeezed time to add a new role to mama, lunch lady, and teaching assistant: playmate. We bought a ping pong table. We practiced some hoops. We took daily walks around the neighborhood, during which the 9-year-old taught me about Pokémon and the world of Percy Jackson. We started to feel a lot better, like we were going to turn the corner and there would be summer break, waiting for us like a long mid-afternoon nap.

When I rallied the energy to write, I worked on my project about fiercely queer and multiracial 1990s-era dance clubs in Los Angeles. One section is on a graphic anthology, Love is Love, that memorializes the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting victims, mostly from Orlando’s Black and Latinx LGBTQ community. With a few exceptions, many stories in the anthology represent problematic responses to the Pulse shooting, such as homogenous gay pride stories on family and societal acceptance from a white, cis-gendered, and male perspective. These narratives erase the mostly Latinx and Black queers at Pulse on Latin night. I’m interested in how Latin and Hip Hop nights may counter predominantly white, and often racist, sexist, and transphobic spaces of the more mainstream clubs and bars in gay centers like West Hollywood and San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood.

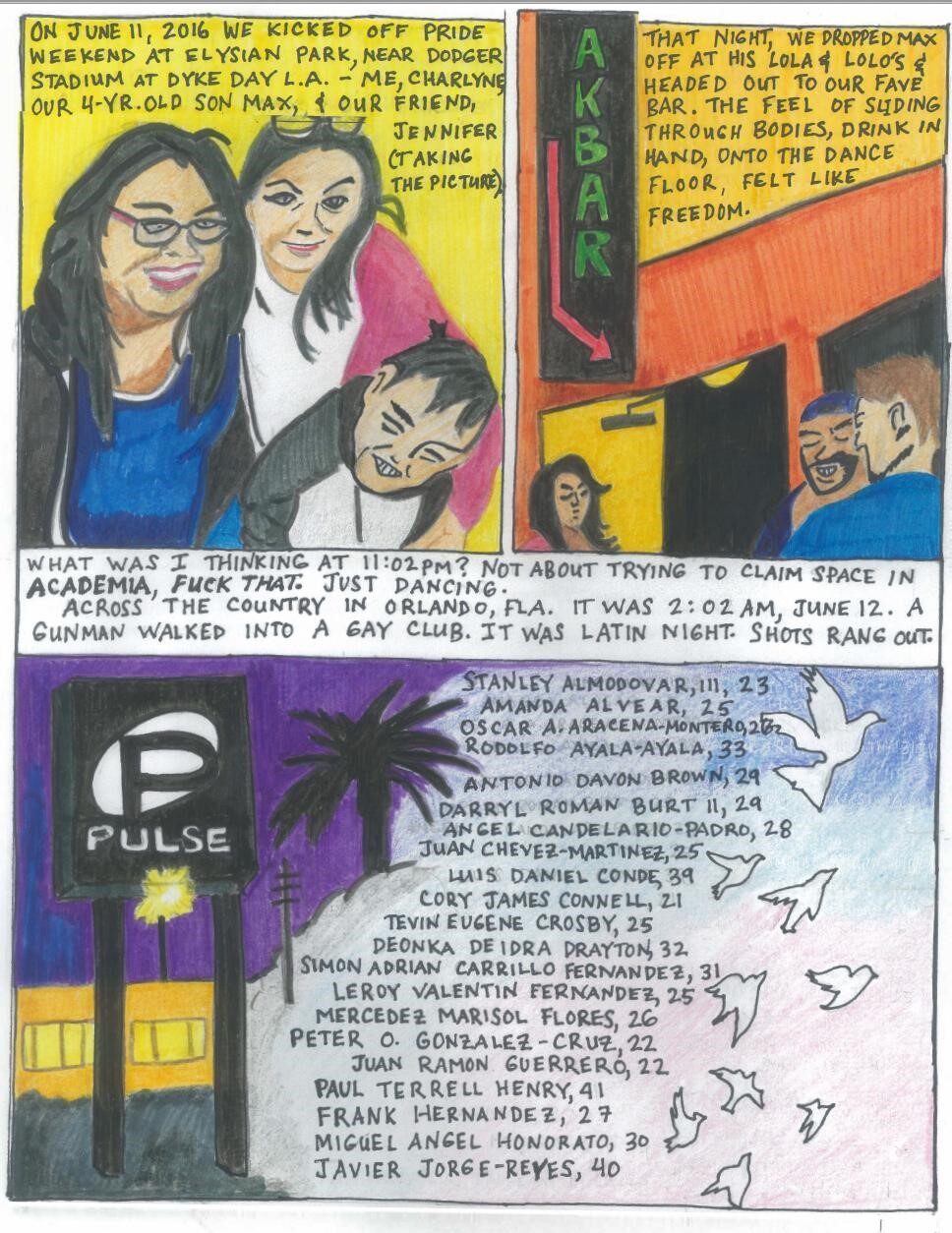

As Filipinx, I’ve always found the queers of color spaces during Pride. My family started celebrating at Dyke Day L.A., an inclusive, intergenerational gathering at a local park. Our first Dyke Day was on June 11, 2016. The Pulse shooting happened later that night (in Orlando, the violence unfolded in the early morning hours of June 12) while I was dancing at a favorite bar with my partner and friends. What if we didn’t come home from the bar that night, and our then-four-year-old suddenly lost his parents? This question still haunts me in 2021, but there is no public commemoration or collective processing of the Pulse mass shooting five years later. In 2020, COVID shut down local Pride events. In 2021, we connect with queer friends in quiet, joyful ways: a hike through the redwoods, an outdoor dinner party, an afternoon at the beach.

Still, I wanted to insert myself into the reflective writing on Pulse, while honoring the victims. I also teach a class on graphic narrative and life writing, with an assignment that asks students to draw a memory from a photograph, and to tell the story of that photograph in a graphic narrative. The first panel from “Come Out and Dance” is drawn from a photo on June 11, 2016. That second pandemic spring, our son missed his friends, and we missed our community. These comic panels represent me thinking through my feelings of another year without collective mourning or celebrations, and how queer community, memory, and trauma can be archived through graphic life writing.

|

|

Image Descriptions:

Panel 1: A family portrait of two women and a young boy, smiling.

Panel 2: Bar patrons standing outside of the bar entrance.

Panel 3: A hand-written list of Pulse victims’ names and ages with doves flying upward and the

exterior of the Pulse nightclub.

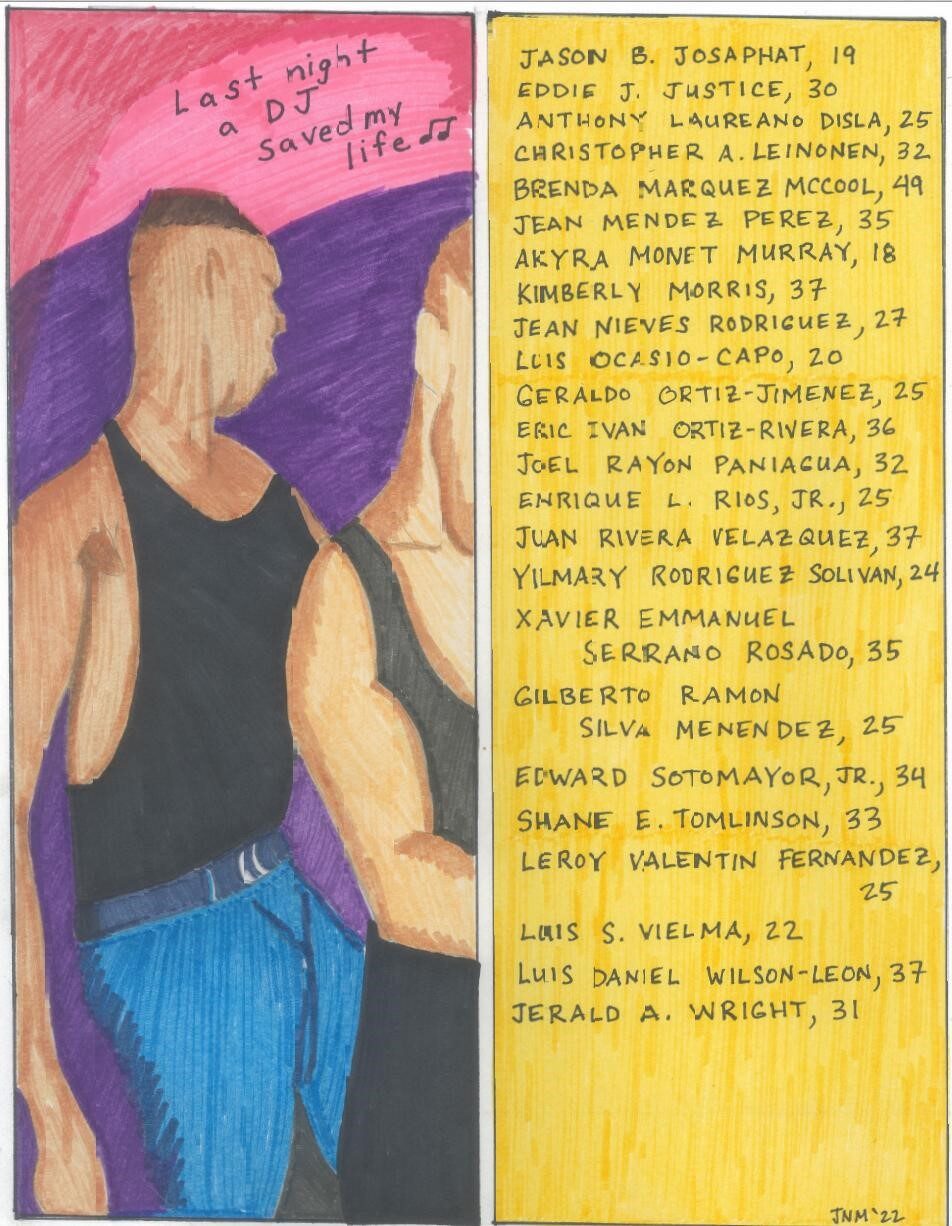

Panel 4: Two men dancing in a nightclub.

Panel 5: A hand-written list of Pulse victims’ names and ages against a yellow backdrop.

Bio

Jolivette Mecenas is an Associate Professor of English at California Lutheran University. She has recent publications in Radical Teacher, WPA: Writing Program Administration, and Open Words: Access and English Studies. She has been a fan of comics writers Lynda Barry and Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez, authors of Love and Rockets, since high school. She has been drawing Garfield for even longer. This is her first published graphic narrative.