imagine we knew all our names

TALISHA HALTIWANGER MORRISON & SHERRI CRAIG

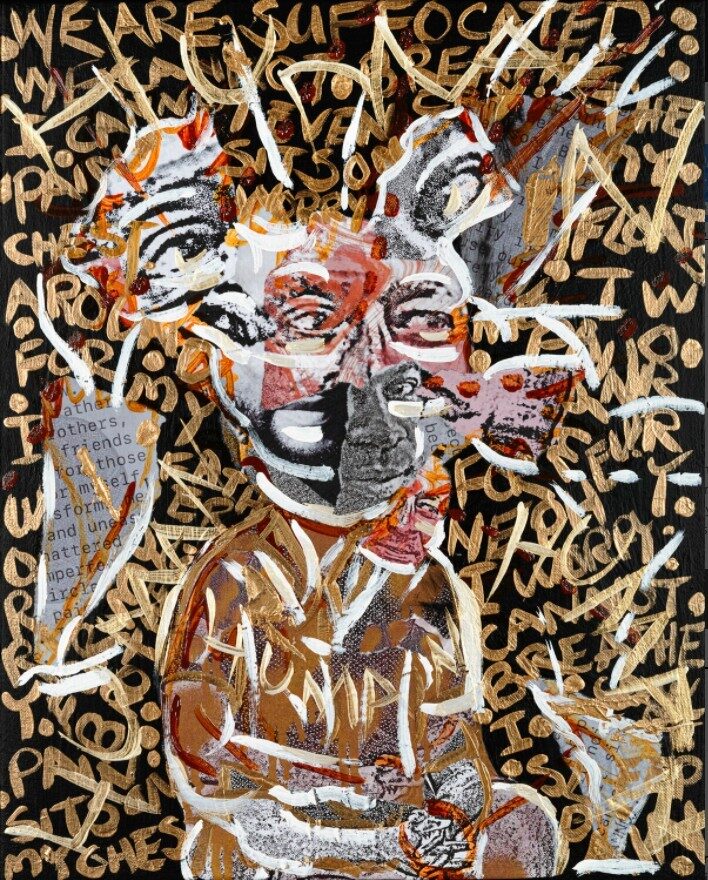

Figure 1: Courtney Minor, Worry. Anger. Systemic. Pandemic.

(2020) Acrylic, Collage on Canvas

intro.

Our experiences in the last three years have felt other worldly. Images of death and despair covered newspaper covers. Every media outlet displayed terrified people in masks, tears in their eyes, chanting in the streets behind armored trucks and police barriers. Grocery stores echoed like canyons, emptied of essential and nonessential goods like toilet paper and flour.

As Black women, the past three years have been new trauma and more of the same. Every new murder of an unarmed Black person is a punch in a still-bleeding wound. Every moment of disrespect and casual cruelty is a slap across the same cheek. As we look toward an imagined future, it is hard not to see the past. But this is our attempt.

We have spent much of the past three years reflecting on our experiences and identities as Black women. Mothers. Wives. Pre-tenure academics. Sisters. Daughters. Friends. Teachers.

Come celebrate

With me that everyday

Something has tried to kill me And has failed

- Lucille Clifton, “Won’t you celebrate with me”

We find inspiration in the words of Lucille Clifton and in other Black women, poets, academics, and artists. We celebrate that we are still alive when Sandra Bland, and Breonna Taylor, and Atatiana Jefferson, and Ashley Cannon are not. We turn to the artwork of Courtney Minor, Worry. Anger. Systemic. Pandemic. (2020) to guide our reflection on our pasts, our strange present, and our imagined future (see Figure 1, work used with artist’s permission).

worry.

sherri elaine craig (sec): In pregnancy and the year after Black mothers are three times more likely to die than white mothers in 2021 (Arias, et al. 2021). Each year in the US approximately 700 mothers die. If all of these people represent only two races (to be clear, they do not), 525 of them would be Black, mothers, and dead. These divergent numbers are even more staggering when considering infant mortality rates: “Overall pregnancy related mortality in the United States occurs at an average rate of 17.2 deaths per 100,000 live births. However, that number jumps to 43.5/100,000 for non-Hispanic Black women and decreases to 12.7/100,000 for non-Hispanic white women” (Melillo, 2020). In light of such numbers, I realized that could have been one of those that did not make it home in 2020. After more than 15 years, my partner and I brought a child into this world. They are beautiful but I spent 40 weeks overcome by worry. The idea of 43.5 infant deaths suffocated me.

I witnessed violence, physical, emotional, and everything in between, to Black bodies every day on the tv. I was worried for myself. Overcome with grief that I had irrefutable proof that I no longer needed to leave my home to perish at the hands of someone designed (at least intrinsically) to keep me safe, I spent nights watching shadows on the wall. In the daytime, exhausted, with racoon eyes, I taught my courses and prepared myself for bringing a Black human into the chaos that had become our lives. How was I to protect them? The coronavirus raged. People raged. I raged. This was more than the typical worry that accompanies any expecting parent.

talisha michelle haltiwanger morrison (tmhm): I learned that I was pregnant with a son just a few days before 12-year-old Tamir Rice was murdered. I watched the video of Tamir Rice’s death, the first and only such video of Black death I’ve ever seen. Sometimes, I look at my son, and am overwhelmed with fear and worry for him. But truthfully, I began to fear for his life before he was even born. I cannot think of Tamir Rice and not remember the pain and fear that shot through me as I touched my stomach and thought of my own little Black boy. I carry that fear, even more now that my son is alive and breathing and the most beautiful thing to ever exist, and also hard-of-hearing and autistic. His behavior is atypical. He does not respond to voices or commands the way most people or children do. And I wonder if there is anything I can do to keep him from becoming like Elijah McClain, a young, Black man, believed to have been autistic, who was killed in Colorado in 2019.

anger.

tmhm: Widespread coverage of Elijah McClain’s death came in close succession to the deaths, or reporting of the deaths, of other Black people: Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and, of course, George Floyd. It took these deaths, and the video evidence of Floyd’s murder, for the world to care about McClain. Suddenly there was a national reckoning around race, including in institutions of higher education. Including in Writing and Rhetoric studies. Our white colleagues suddenly took us seriously, having borne witness to the unflinching truth in Darnella Frazier’s video. Antiracism reading groups and statements were plentiful. And, to be honest, the whole thing made me angry. The shock and dumbfoundedness that my white colleagues expressed was painful. So much violent and public ending of Black life should not be necessary for us to be believed. I was skeptical of their commitment amongst reports of increased support for Black Lives Matter among white Americans. And now, I’m unsurprised by their declining interest and support, as a poll by Civiqs found that as of March 2022, only 32% of white respondents express they support the movement. Recent years for me have been full of anger, hurt, exhaustion, and also, resolve. As Audre Lorde says, “Anger is useful to help clarify our differences,” but anger and the strength it brings do not “focus upon what lies ahead, but upon what lies behind” (Lorde, 1984, p. 152).

sec: There were days in the last three years where I simply listened to music while sitting in the dark, nursing my infant son. I built complex playlists where artists screamed and cursed their throats raw. Gangsta rap, conscious hip hop, hyphy rap, really anything that could capture the anger and resentment inside of me that I felt unable to express while growing a Black person and then keeping them alive. Each day the task of keeping myself alive became even more burdensome. News of police invading Black women’s homes and violating and/or murdering them echoed inside of me -- Atatiana Jefferson, Breonna Taylor, Anjanette Young -- these women who are peacefully in their homes, often with children present, had no forewarning that they were not safe. How does one sleep with the knowledge they are not safe in their bed? I didn’t sleep for months. I was too damned angry.

In the opening to her song “Black Rage,” Lauryn Hill harmonizes, “Black rage is founded on two-thirds a person / Rapings and beatings and suffering that worsens.” Much like Lorde, she reminds us that the root of anger is in the past wrongdoings and harms. By altering Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “My Favorite Things” (1959) (from The Sound of Music) as John Coltrane (1961) does with his soprano saxophone version of “My Favorite Things,” the audience is forced to consider whose favorite things might be the rapings, beatings, and sufferings of Black folx. “Black Rage” ends with “Black rage is founded on denial of self.” Our collective denial of self, to be ourselves, safely, to 80 years old, the average lifespan for white women (Arias, et al. 2021), remains elusive. Filled with anger, I kept listening to music in search of solace. In addition to the rage filled rap playlists, I turned to the haunting sounds of Black women crying out in anger, joy, and fear.

systemic.

tmhm: I am one of approximately 20 full-time Black women faculty on my campus. We make up just 1.1 percent of full-time faculty and 3.2% of all Black women employees, including faculty, staff, and student employees. M. Cristina Alcalde (2021) notes, across the country, Black women hold just 1.6 % of full professorships, and Black women and other women of color are often laden with heavier service burdens. Departments and institutions, particularly predominantly and historically white institutions (PHWIs), often profess their commitments to diversity and inclusion, calling upon women of color to lead the change, only to later punish us/them for having less time to publish. The systemic inequality of higher education leaves Black women burnt out. Overworked and isolated, Black women get stuck or pushed out of their positions, trying to seek a space that might be slightly less oppressive, knowing that they are unlikely to find it.

You ain’t got no one to hold you You ain’t got no one to care

If you’d only understand, dear Nobody wants you anywhere

-Nina Simone, “Blackbird”

sec: Institutions, writing studies departments, and national organizations released a series of statements and responses in support of the anti-police violence demonstrations which occurred in the summer of 2020. These responses to BLM actions were plentiful and often contained cookie cutter language about supporting Black students and a commitment to antiracism and linguistic justice without also addressing the systemic problems within their domains. The absence of systemic changes in these statements or in many public facing digital spaces communicates that change is not the ultimate goal, but rather the demonstration of care. In order to demonstrate a real care ethic these programs needed to establish a sustainable responsibility and responsiveness to the Black students, staff, and faculty on their campuses and organizations. Most have failed to do more than insert a few reading groups, discussion circles, and diversity hires and done nothing systematically to ensure the safety of the most vulnerable. Ensuring all involved participate in the crafting of a better future for Black folx.

pandemic.

Pandemic. adj. /panˈdemik/

From Greek for all (pan) and people (demos); prevalent over a whole country or the world.

We have come to associate the word pandemic with COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2. However, another, non-biological pandemic has existed for centuries. Racism involves all people all over the country and all over the world. The Black diaspora is global, so too is racism, so too is this pandemic. Lives have been lost and worlds have been altered due to the hatred and inhumane treatment inflicted. Throughout 2020 and 2021 the coronavirus has disproportionately impacted BIPOC communities, in more ways than white communities in the same states. As of March 2022, the CDC reports[1] that Black people are 1.7 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than their white counterparts and 2.4 times more likely to be hospitalized. Just below these devastating figures, the CDC website remarks “Race and ethnicity are risk markers for other underlying conditions that affect health, including socioeconomic status, access to health care, and exposure to the virus related to occupation, e.g., frontline, essential, and critical infrastructure workers.” This attention to the systemic reasons the Black, Hispanic, Indigenous, and other historically minoritized populations are at greater risk further highlights the pandemic’s deep roots into our country’s historical and present hatred for anything not white and with disability.

We both started our current positions during the Covid-19 pandemic, Talisha in July of 2020 and Sherri in August of 2021. We endured major transitions in the midst of social, cultural, political, and medical turmoil. We arrived at our new institutions still one of few Black women faculty and now facing heightened isolation as others who might normally have reached out to welcome us, to waymake with us, struggled under the weight of the ongoing pandemic and its impact on their courses, research, and personal lives. As Black women, the past three years have seen new trauma and more of the same: fear, anger, exhaustion, and isolation. But, also, survival. This pandemic has tried to kill us. Our institutions have not helped. But we are still here.

conclusion.

We have structured this brief piece on the title and the emotions elicited by the Minor’s mixed media collage, constructed with eyes and hands in black and white superimposed upon a black background with the words: “We are suffocated. We cannot breathe. I cannot even cry. The pain sits on my chest. Worry floats around me. I worry for my nephew. I worry for my brother. For my father. I can’t sleep.” Upon discovering Minor’s artwork, we were astounded by the depth of its ability to capture so much of a collective reality for many Black folx.

While we worry for our nephews, brothers, and fathers, we, too, worry for our children. We worry for ourselves. We are angry for our communities. We are angry for the Black women and people taken by violence and neglect and systemic racism. We imagine a fantastical future where worry and anger do not consume us. Where the pandemics of the coronavirus and racism do not ravage our communities. We picture a fantastical world where it is safe to be in our homes, in our cities, in our departments, and in our classrooms. A world where we can breathe. Where we don’t know the names of Black women because they are trending for a short while. It doesn’t have to look like Wakanda, tucked away from the rest of the world, protected by invisible surveillance. The future does not deny us air.

playlist.

Our song collection brings us strength, and joy, and (useful) anger, and resolve. There are many more to add to the list. We hope they bring you inspiration.

https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLruS_uDQYeZN8dSq1vY4xoxKeH_O23Ah_

References

Alcade, M. C.M. (2021, December 17). Colleges must redefine leadership. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2021/12/17/colleges-should-support-women-faculty-color-leaders-opinion

Arias, E., Tejada-Vera, B., and Ahmad, F. (2021, February 1). Provisional life expectancy estimates for January through June, 2020. Vital Statistics Rapid Release, Number 010. Center for Disease Control. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/VSRR10-508.pdf

Civiqs. (2022, March 29). National Black Lives Matter, registered voters. [data set]. Retrieved from https://civiqs.com/results/black_lives_matter?uncertainty=true&annotations=true&zoomIn=true

Melillo, G. (2020, June 13). Racial disparities persist in maternal morbidity, mortality and infant health. American Journal of Managed Care. Retrieved from https://www.ajmc.com/view/racial-disparities-persist-in-maternal-morbidity-mortality-and-infant-health

Minor, C. (2020). Worry. Anger. Systemic. Pandemic. [Collage, Paper on Canvas]. Saatchi Art. https://www.saatchiart.com/art/Collage-Worry-Anger-Systemic-Pandemic/1397981/7744 989/view

Williams June, A. and O’Leary, B. (2021, May 27). How many Black women have tenure on your campus? Search here. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-many-black-women-have-tenure-on-your-campus-search-here

___________________

[1] Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death By Race/Ethnicity (CDC)

Dr. Sherri Craig, an Assistant Professor of Rhetoric and Writing at Virginia Tech University, researches how universities and workplaces implement diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging initiatives, particularly for the recruitment and retention of Black women. She also considers the ways in which diversity programming can be located in writing across the curriculum initiatives. She regularly offers courses and workshops on navigating diversity and inclusion in the workplace and across the curriculum. Her published work can be found at sparkactivism [dot] com, the Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, and in the WPA: Writing Program Administration journal.

Dr. Talisha Haltiwanger Morrison Talisha Haltiwanger Morrison (she/her) is the Director of the OU Writing Center, Director of the Expository Writing Program at the University of Oklahoma, and Assistant Professor of Writing at the University of Oklahoma. Haltiwanger Morrison’s research interests include writing center administration, Black feminist studies, and community-engaged writing. Her work has appeared in publications such as Writing Center Journal, Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, and The Peer Review.