Making Music, Enhancing Agency: A Case Study Analysis of Agency-Affording Multimodality in Kehinde Spencer’s A Woman’s Reprieve

Christine Martorana, College of Staten Island - CUNY

HTML | PDF

Author’s Note

I recognize that my status as a white woman prohibits me from ever facing the double layering of subjugation that Black women experience. One way I have tried to account for this is by weaving Kehinde’s voice and perspectives throughout this discussion. As Friedman points out, white academics too often “write about [B]lack women [while failing] to include real [B]lack women in the discussion or to understand [B]lack women as cultural producers rather than simply as objects of the racial gaze” (4). Thus, it has been my intention throughout this discussion to keep Kehinde’s voice and ideas central, to let her speak for herself. Additionally, from the start of this project, Kehinde has graciously read and responded to my analysis and writing, offering her support and suggestions along the way. My hope is that as a result of these rhetorical decisions throughout the composing process, I am able to present A Woman’s Reprieve for what it is: an innovative, multimodal, and effective enactment of feminist agency.

Unlike white women whose “white skin privileges them” (Collins, 1993, p. 25), women of color experience oppression due to their gender and skin color – a double layering of subjugation that lends legitimacy to Tasha Fierce’s claim that “Black women occupy a social status lower than that of white men, Black men, and white women” (2015). However, women of color refuse to be victimized; instead, they develop effective and creative ways of speaking back to this oppression. One such way is through multimodality. As Gunther Kress (2000) points out, “the intentional deployment” of multimodal modes within the creation of a text “gives agency of a real kind to the text maker” (p.340). In this article, I present an example of how one Black woman artist with Nigerian roots harnesses the agency-affording potential of multimodality.[1] Specifically, I present a case study analysis of A Woman’s Reprieve, a feminist music album released in 2008 by my friend, Kehinde Spencer.[2] My claim is that the purposeful combination of visual, linguistic, and aural modes is an act of feminist agency for her, one through which she calls upon her African heritage to present herself as a valued and valuable member of her African culture.

One way of understanding the potential for multimodal self-presentation to offer a source of feminist agency is through a consideration of mainstream representations of Black women. Privileged by neither their gender nor their race, Black women must often see themselves portrayed as hypersexualized beings, skewed representations that have roots deep in our nation’s history. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, for instance, “slavery defined African American women as society’s Other, [as lesser-than beings] unable to control [their] sexuality” (Littlefield, 2007, pp. 678-9). Otherwise referred to as “the oversexed jezebel” (Patton, 2006, p. 26), this hypersexualized representation marries the woman-as-object framework with the image of “black slave women…put up on the auction block” (Nykol, 2015). The resulting depiction is the African American woman “as promiscuous, erotic, and sexually available” (Bromley 87). She is, in these conceptions, little more than a physical body available for the viewing, purchasing, and sexual pleasure of the men around her.

Today, movies, magazines, and music videos continue to promote this degrading representation, what Marci Bounds Littlefield describes as “sexually insatiable images” (p. 681). Take, for example, African American rapper David Banner’s 2003 hit single “Like a Pimp.” The music video features multiple shots of Black women shaking their behinds while men look on, rapping lyrics such as, “F*** yo gul up in the throat / And make her swallow the nut” and “We got all the butts and / All of they sluts and / All of the hoes.” In the background are sounds of women moaning, noises representative of an orgasm that we are to assume is the result of the men taking full advantage of Black women’s sexual availability and eagerness. What is even more troublesome is that the repercussions of such representations extend into the lived experiences of Black women, making “rape and other forms of violence against [these] women an acceptable norm” (Littlefield, p. 681).

In response to degrading representations such as this, Black women have located ways of speaking back, of engaging in acts of feminist agency that reframe these “twisted images of Black womanhood” (Richardson, 2002, p. 676). Here, I showcase the efforts of one such woman. As the following discussion will show, Spencer’s A Woman’s Reprieve offers a model for the multimodal enactment of feminist agency. My claim is that Spencer enhances her feminist agency by skillfully combining visual, linguistic, and aural modes as a means through which she presents herself as a woman within her African culture. In so doing, she invites a productive shift in the focus upon Black women’s bodies from one that is merely sexual to one that is purposefully cultural, and, as the following analysis reveals, multimodality impels this agency-affording shift.

A Woman’s Reprieve

A Woman’s Reprieve features 17 tracks, each of which contains lyrics and melody composed by Kehinde while featuring various singers and musicians as guest performers. Through the use of spoken word, instruments, photos, and song, this “album chronicles a young woman’s journey into womanhood” (Spencer, 2008).[3] The album begins with Kehinde in the midst of heartbreak.[4] She is facing the end to an unhealthy relationship with a man who is married to another woman, and we quickly learn that Kehinde’s relationship with this man is based on her physical submission to him. As she contemplates ending this relationship, she faces the fear of being alone, a fear that Kehinde describes as part of the “pain, healing, transformation, and the cycles of growth women need to experience to understand what it means to live as divine human beings.” Thus, Kehinde’s intended audience is comprised of women struggling through similar heartache and change. In one of the early songs on the album, Kehinde writes, “Freedom is what I deserve / But chains are all that I see / Holding me in a space of fear / So I won’t get free” (Spencer, 2008). Each song on the album represents a step in Kehinde’s personal journey, and by the end of A Woman’s Reprieve, Kehinde has progressed from a place of heartache to one of self-love and cultural awareness. Various visual, linguistic, and aural modes drive Kehinde’s progression from a woman defined by her sexual relationships with men to a woman self-defined in relation to her African roots.

Multimodality and Feminist Agency within A Woman’s Reprieve

Visual Mode

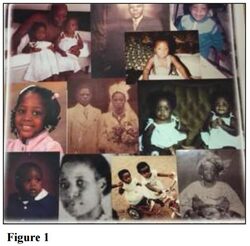

One of the main visual modes Kehinde uses in A Woman’s Reprieve is the inclusion of personal photos. These photos appear on the exterior cover of the album and also within the print insert that accompanies the CD, making visual the connection between Kehinde and her African culture. Two representative examples will illustrate this visual mode. Figure 1 features a collage of 11 family photos taken during the first eight years of Kehinde’s life when she was living in Nigeria. As such, each photo offers a visual testament to Kehinde’s situatedness within a network of her African culture. The collage appears on the second to last page of the print insert, adjacent to the written acknowledgements of those who helped with the production of the album. Accordingly, this collage is not explicitly linked to any particular song on the album. Rather, it functions as a visual conclusion to the album as a whole, a graphic representation of the link between Kehinde’s personal story as presented in A Woman’s Reprieve and her cultural past.

According to Kehinde, the decision to include photos such as these was a purposeful effort to pay homage to her cultural roots and to acknowledge that this history is inseparable from her current identity. She explains, “People are dynamic human beings. There are multiple layers, and in one single moment, you are meeting somebody’s past and future. So it was important to put [the collage of photos] in there” (Personal interview). From this perspective, we can recognize the ways in which the collage of photos explicitly links Kehinde to her African heritage. Her childhood in Nigeria is given visual presence as are her parents, grandparents, and siblings. Kehinde does not solely claim her African roots; rather, she uses the visual mode to graphically spotlight these roots, inviting her viewing audience to appreciate this component of her identity on a more intimate and personal level.

Furthermore, the very form of the photos provides a visual representation of the cultural network within which Kehinde situates herself. That is, the actual presentation of the photos – the ways in which they touch and overlap one another to form a collage – visually communicates interconnectedness. The photos are not presented as separate and individual. Rather, each photo functions as one piece of the larger image that is the collage; if one photo were missing, the collage would be incomplete. The fact that the photos feature both Kehinde and her African family members invites us to adopt a similar view of Kehinde’s connectedness to and value within the African culture.

One way of understanding this rhetorical strategy is as a manifestation of what Susan Stanford Friedman calls narratives of relational positionality. According to Friedman (1999), narratives of relational positionality recognize “how the formation of identity, particularly women’s identity, unfolds in relation to desire for and separation from others. [These narratives acknowledge that] identities are fluid sites that can be understood differently depending on the vantage point of their formation or function” (p. 17). Thus, by presenting herself within this specific collage of photos, Kehinde invites us to understand her identity within the context of her familial and cultural relationships. We are invited to recognize that just as each photo is a necessary component to the collage, Kehinde herself is an integral component of her African community, a recognition that offers a significant departure from mainstream hypersexualized notions about Black women.

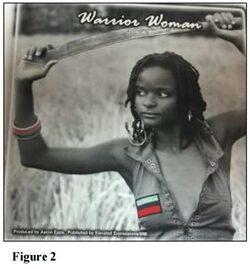

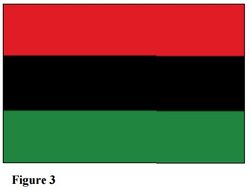

A second example of this visual mode is provided in Figure 2. This photo offers a different visual than the previous example; here, Kehinde does not feature any people other than herself. Additionally, this photo is a single image rather than a collage. However, it still brings Kehinde’s African culture to the visual fore. The photo features Kehinde standing in an outdoor field, holding a long, narrow tool above her head. The entire photo is black and white with the exception of her bracelets and the patch on her shirt, both of which feature the specific colors green, black, and red. Here, Kehinde’s cultural connection is made explicit through this specific use of color. The colors emphasized on Kehinde’s patch and bracelet are those featured on the Pan-African flag, and the shape and pattern of the patch resembles that of the flag as well (see Fig. 3). Created in 1920 by the Universal Negro Improvement Association, the Pan-African flag is a “nationalist symbol for the worldwide liberation of people of African origin” (“Pan-African Flag,” 2015). By wearing and drawing visual attention to these colors, Kehinde explicitly uses the visual to connect herself to a Pan-Africanist ideology, a belief in worldwide unity for Africans. As a result, we are invited to see Kehinde as a member and supporter of this cultural network. She explains, “I believe that the individual is part of the community. The individual is not separate, and that is very much tied to my African upbringing and my African culture. […] The individual is always part of the community, even if you go out, you’re still connected, you’re still tied” (Personal interview). In Figure 2, Kehinde uses the colors green, black, and red to give material presence to these community ties.

This observation is illuminated by Maria Martinez Gonzalez’s discussion of a feminist collective identity. In “Feminist Praxis Challenges the Identity Question: Toward New Collective Identity Metaphors” (2008), Gonzalez likens a feminist collective identity to an archipelago – a collection of islands – wherein individual islands “have to coexist in their differences” (p. 33). She goes on to explain that “archipelagos are not ‘natural’ entities [in that] islands do not belong ‘naturally’ to an archipelago” (p. 33); rather, people set boundaries and make decisions that dictate “if an island is inside or outside the archipelago” (p. 33). Similarly, no single person belongs ‘naturally’ to any collective identity; that is, we can claim or reject collective identities based upon the choices we make regarding the representations of our bodies. Since these choices are often made for Black women, it is an act of agency for Black women to purposefully decide how to represent themselves and which collective identities to claim or reject. Kehinde does just this when she dons the Pan-African patch (see Fig. 2), a purposeful choice through which she claims a collective African identity. Put simply, Kehinde uses the visual mode to claim that despite appearing alone in the photo, she remains connected to her culture.

Not only does this visual choice connect Kehinde to her African roots, but it also offers an effective enactment of Black feminist agency. Specifically, claiming “broader…networks, both kin and nonkin,” offers a means through which African and African American women can locate “a site of cultural resistance” (Peterson, 2005, p. 15). Within a white, hegemonic culture that conceptualizes Black women as “promiscuous…and sexually available” (Bromley, 2012, p. 87), this can be an especially salient act. That is, by situating themselves within a larger cultural network, African American women can reach “beyond the family into the…community” (Peterson, 1995, p. 16), claiming their value before those both within and beyond the domestic realm. As evidenced in Kehinde’s visual connections to both her family and the larger Pan-African community, this offers an effective way for Black women to present themselves beyond the hypersexualized framework that too often accompanies public representations of their bodies.

Additionally, the fact that Kehinde visually challenges this framework is significant for our understanding of the ways in which multimodality can enhance feminist agency. According to Caroline Wang, Mary Ann Burris, and Xiang Yue Ping (1996), “Photographs can communicate the voices of women who ordinarily would not be heard” (p. 1396). While this is certainly a valid observation, Kehinde’s use of photos suggests that the visual can do more for Black women.

That is, not only can photographs communicate the seldom-heard voices of women, but they can also reveal seldom seen images of women. Kehinde’s purposeful choice of photos illustrates this potential. Each photograph she includes explicitly promotes a cultural view of who she is as a Nigerian American woman, a significant divergence from traditional Westernized conceptions. In short, Kehinde effectively uses the visual mode to shift the public gaze on her body from an outwardly-defined sexual focus to a self-defined cultural focus, promoting what Littlefield calls “alternative, positive images [of] the African American woman” (pp. 680-681). Although Kehinde’s visual choices do not erase pre-existing, oppressive conceptions of or perspectives on African American women, they do function as meaningful acts of feminist agency, challenging skewed perspectives through the circulation of alternative images.

Linguistic Mode

Kehinde’s rhetorical prowess is not limited to the visual. She skillfully wields the linguistic mode as another means of promoting her African cultural connection and enacting feminist agency. For instance, “My Ancestors,” track twelve on the album, includes the following lyrics: “My ancestors did so much for me / My ancestors allow me to be / I give thanks for standing on their shoulders / Protected so now I am much bolder.” In writing these words, Kehinde linguistically acknowledges her ancestral connection, recognizing that her identity as a Nigerian American woman benefits from the sacrifices made by her ancestors. As the song continues, Kehinde continues to explore these familial connections, eventually stating that she is inseparable from her ancestors. She writes: “They are me, me are they / I’m so glad I know the way.” Here, the linguistic connection that Kehinde presents to her ancestors is such that she becomes indistinguishable from them: “They are me, me are they.” In short, she uses the linguistic mode to establish a direct connection between who she is and her ancestors, to emphasize her intimate relationship with and inseparability from her African roots.

A similar use of this mode appears on the inside back cover of the album where the following words are written: “All of my mothers gave me a power. I have walked in their footsteps. Now I have come to this hour. Must step out the shadow. Must step in the light. Stand as a soldier. Stand ready to fight. I am a Warrior Woman!” Similar to the lyrics of “My Ancestors,” these words linguistically evoke an ancestral perspective within which Kehinde situates herself. In so doing, Kehinde promotes and draws attention to her cultural connections. Additionally, it is significant that Kehinde concludes this excerpt with the claim, “I am a Warrior Woman!” The phrase “Warrior Woman” is also printed above the photo of Kehinde presented in Figure 2. Similar to Kehinde’s linguistic connection to her ancestors and mothers, these written words situate Kehinde among a long tradition of other African and African American women. According to Jacqueline Jones Royster, “The metaphor of African American women writers as warriors for social justice” is commonly invoked within discussions by and about African American women (p. 51). For instance, Audre Lorde (1984) uses this metaphor to describe herself: “Because I am woman, because I am Black, because I am lesbian, because I am myself – a Black woman warrior poet doing my work – [I] come to ask you, are you doing yours?” (p. 42). And, Diedre Bádéjo (1998) acknowledges the warrior imagery that frequently accompanies “African American poetic images of ‘women [and] mothers’” (p. 108). As these references suggest, it is common for African American women to conceptualize themselves as warrior women, “passionate thinkers and activists who use the pen as a mighty sword” (Royster, 2006, p. 51). Kehinde takes advantage of this metaphorical construction by using the linguistic mode to enact this very identity. In other words, not only does Kehinde discursively connect herself to her African roots, but she also uses the linguistic mode to function as a warrior woman.

Additionally, Kehinde’s decision to evoke the Warrior Woman metaphor offers a powerful and impactful act of Black feminist agency. Similar to the aforementioned acknowledgement of her ancestral mothers, this connection to the warrior woman communicates the message that Kehinde is not simply a “[B]lack receptacle of male desire” (Lhooq, 2014); rather, she is an intellectual member of a larger African community – and, more specifically, a community defined by other active, engaged Black women. This is a significant act of feminist agency for Kehinde because it offers a means through which she presents herself as an active woman engaged in her African culture rather than a passive body on display.

Thus, in purposefully using the linguistic mode to connect herself to her ancestors and mothers, Kehinde shows herself to be a woman capable of using “the performative power of the word” (Peterson, 1995, p. 3, added emphasis) – rather than the performative power of a hypersexualized body – to interact with the world around her.

Aural Mode

Finally, Kehinde engages the aural as a means of both presenting herself in relation to her African culture and enhancing her feminist agency. This is evidenced in the spoken conversations between Kehinde and her grandmother. These conversations occur regularly on A Woman’s Reprieve, each conversation immediately preceding a song. Additionally, the dialogues are only presented aurally, never appearing in writing alongside the lyrics. As a result, the spoken conversations take full advantage of the aural mode by privileging a strictly listening audience. For instance, “The Sun is Leaving” is the third track on the album. At this point in A Woman’s Reprieve, Kehinde is still reeling from the pain of an unhealthy relationship with, and dependence on, a married man. In the conversation that immediately precedes this song, we hear the following:

Grandma: “What’d you say, baby?”

Kehinde: “I’m ready to listen Grandma, please! Please! I’m ready to listen.”

Grandma: “Just breathe, baby. I know it ain’t easy, but you have to go through this.”

Kehinde: “I’ll do whatever you say, Grandma. Please, I can’t do this anymore. Just tell me something, Grandma, I can’t do this anymore.”

Grandma: “Okay, baby…”

As the Grandma’s voice fades away, the song “The Sun Is Leaving” begins. Since this conversation is not printed within A Woman’s Reprieve, it privileges the listening audience. Thus, we must attend to the aural expression of these words in order to gain a full understanding of their meaning. To facilitate this understanding, I draw upon Heidi McKee’s six elements of vocal delivery.

At the start of Kehinde’s dialogue with her grandma, her grandma’s voice has a breathy quality, communicating an intimate closeness. Her voice is low and smooth as she asks Kehinde, “What’d you say, baby?” Kehinde’s response, however, is full of tension, tight and rushed. She sounds as if she is in the midst of crying. The pitch of her voice is much higher than that of her grandma. Her breath is short and heavy; she draws out the words “please! Please!” in a trembling tone. Her grandma, however, maintains a relaxed, low manner, her voice barely above a whisper as she reminds Kehinde to “just breathe.” There is an audible contrast between Kehinde’s voice and that of her grandma – one is loud, tense, and high; the other is soft, calm, and fluid. As a result, we are invited to recognize the grandma as a calming, wise presence in Kehinde’s life, an understanding facilitated by our ability to hear the conversation rather than read it. That is, through Kehinde’s staccato breathing and strained, trembling words, we hear the pain and anxiety in her voice. Through the soft, gentle volume of the grandma’s voice, the low pitch and the ways in which one word melodiously blends into the next, we hear the calmness and composure that she brings to the conversation. The aurality of this dialogue – the ability to hear the volume, pace, and tension – is integral to grasping its complete meaning.

A similar observation can be made regarding the spoken conversation that precedes “My Mother’s Daughter,” track four on the album. This conversation occurs after Kehinde’s decision to end the relationship:

Grandma: “You have to figure out what’s missin’ in you. That’s what you want him to fill up. Baby, get up! The sun is shinin’. So you must too. God gave you another chance at life. What you gonna do with it? You hear me? What you gonna do?”

Kehinde: “It still hurts.”

Grandma: “It’s gonna hurt. Nothing will ever stop the pain. But one day you’ll learn that you can live with it. Pain can’t stop you from movin’ forward.”

Kehinde: “I still miss him!”

Grandma: “That’s fine. But the sun is shinin’. So what are you going to do?”

Similar to the previous example, the aural expression of this dialogue is central to grasping its full meaning. Here, the grandma’s voice is not quite as airy as in the previous conversation. Rather, there is a slight tension and faster pace to her spoken words, aspects that communicate a sense of urgency as she asks Kehinde, “What you gonna do with it? You hear me? What you gonna do?” Kehinde does not respond immediately; rather, there is a several second silent pause before she finally makes audible, in a slow, soft voice, “It still hurts.” Here, Kehinde’s voice does not communicate the same stress and strain as it did previously. Instead, a sense of exhaustion characterizes her expression, and we hear Kehinde’s tiredness in the slow pace and quiet volume with which she responds to her grandma. When her grandma reacts to Kehinde’s admission of her hurt, she does so with softness and intimacy. The breathiness and fluidity of her voice has returned, and she assumes a more soothing approach. However, this is not mirrored in Kehinde’s response. Instead, Kehinde’s exclamation, “I still miss him!” sounds forced out of her throat. The words are spoken quick, coupled with a sob that gives audible presence to Kehinde’s pain.

In both of these dialogues, Kehinde takes full advantage of the aural mode as a way of situating herself within her culture. Specifically, in aurally rendering these conversations and privileging a listening audience, Kehinde engages in a practice common within Black discursive traditions. As Valerie Chepp (2012) points out, “the centrality of oral tradition and an appreciation for verbal dexterity in African American culture” appears in many forms (p. 224). Modern day examples include “the call and response that takes place during the [African American] sermon” (Banks, 2011, p. 48), “poetry slams” (Chepp, p. 233), and “hip-hop culture and rap” (Grace, 2004, p. 484). From this perspective, we can appreciate the ways in which Kehinde’s decision to incorporate spoken dialogues throughout A Woman’s Reprieve allows her to call upon the oral tradition that characterizes much African American discursive practice. In so doing, she underscores not only her connection to these oral traditions, but also her willingness to carry them on in her own work.

This aural mode offers more than a means of cultural connection for Kehinde. It is also offers an avenue through which she acts as a feminist agent. African American women, in lending their voices to a white, hegemonic public sphere, must negotiate “a paradox of visibility and agency” (Carey, 2012, p. 131). That is, because the Western public sphere privileges “a European rhetorical” perspective (p. 131), non-white rhetors and their work are often re-presented in Eurocentric terms. Thus, African American women often find that they are represented by the dominant majority as race-less rhetors. However, as Elaine Richardson points out, there is no such thing: we exist “in a racialized, genderized, sexualized, and classed world” (p. 680), and ignoring the ways in which these identities shape discourse is a mark of the privileged white man. Still, this inaccurate and harmful practice persists, and as a result, Black women too often find that their “words are remembered, but [their] struggle is forgotten” (Carey, p. 131). In essence, their words get stripped from their bodies, entering public discourse seemingly unattached to the body from whom they originated – and, as previously discussed, when mainstream culture does acknowledge the Black woman’s body, it is often only as a hypersexualized body stripped of her words and intellect.

However, as Richardson points out and this analysis suggests, “the Black female [has] develop[ed] creative strategies to overcome [this] situation” (p. 680). That is, Black women are not silent nor are they passive; rather, they take advantage of specific strategies through which they enhance their feminist agency. My analysis of the aural dialogue on A Woman’s Reprieve suggests that vocal delivery is one such strategy. That is, by engaging the aural through diverse vocal enactments, Kehinde brings the physicality of the Nigerian American woman’s body to the fore, ensuring that her words do not, in fact cannot, circulate separate from her body. She purposefully uses the aural mode to emphasize the relationship between her physical body and her words. As a result, we cannot experience the words without also experiencing the body that communicates these words. Put another way, through the aural mode, the physicality of Kehinde’s body, rather than being ignored or overlooked, is made central – and made central in such a way that Kehinde’s body is presented as an active, purposeful purveyor of the spoken word rather than a hypersexualized body on display by and for the benefit of

others.

Implications

In her discussion of the use of multimodality among South Africans, Liesel Hibbert (2009) identifies what she calls “multimodal self-representation” (p. 212), an act that can lead individuals to see themselves as “agents of change in their own lives” (p. 203). My analysis builds upon Hibbert’s observation, suggesting that Kehinde engages in what we might consider Black feminist, multimodal self-representation: the act of using multiple modes to move from a woman defined by her sexual relationships with men to a woman self-defined in relation to her cultural roots. Kehinde echoes this sentiment as she reflects on the personal impact of creating A Woman’s Reprieve:

I would say the main benefit [of making A Woman’s Reprieve] was realizing what I could do if I put my mind to it – as simple as that sounds…I felt [I] was enacting [feminist] agency because [A Woman’s Reprieve] allowed me to be proactive. It allowed me to use my energy in a positive direction. It allowed me to do something that could teach me things and give me skills, as opposed to sitting at home and crying and feeling sorry for myself because my relationship didn’t work out the way that I wanted it to. (Personal interview)

Undergirding Kehinde’s reflection is an acknowledgement of herself as an agent of change – as a woman with the potential to create and take action in her own life, to re-present herself as a woman defined by her cultural connections rather than her sexual relationships.

Additionally, although Kehinde does not name the specific “skills” she gained while working on A Woman’s Reprieve, I suggest that one such skill is the ability to strategically employ multimodality. My suggestion can be understood in light of Richardson’s discussion of the multiple “literacies [Black women have] developed to fulfill a quest for a better world” (p. 678). Richardson identifies several literacies, including “storytelling, performative silence, [and the] strategic use of polite and assertive language” (p. 687). Each of these literacies, Richardson asserts, provides a means through which Black women use “verbal and nonverbal communication strategies” to challenge racial and sexual oppressions (689). My analysis adds an additional literacy practice to this repertoire – that of multimodality. That is, as A Woman’s Reprieve illustrates, the ability to strategically employ multiple modes in a single text is a literacy skill that bolsters African American women’s enactments of feminist agency.

One specific benefit multimodality affords is multiplicity. Specifically, the multiplicity inherent within multimodality – the combination of multiple modes within a single text – offers a valuable source of agency for African American women. As previously noted, Black women are challenged on multiple fronts. By non-Black women, they are often looked down upon as a result of their race; by white and Black men, they are often denigrated due to their gender. However, as Kehinde reveals, multimodality can be an apt means for Black women to clap back at the multiple discourses that seek to limit their agency. By simultaneously employing various modes – such as the visual, linguistic, and aural ones present within A Woman’s Reprieve –African American women can engage in more than one act of self-representation at a time. They can, to borrow Richardson’s terms, navigate their “multiple consciousness” (p. 686) through multiple modes. For instance, they can visually reject sexualized representations of their bodies – as Kehinde does – while at the same time linguistically situating themselves among other African American Warrior Women and aurally claiming African American discursive traditions. Put simply, the combination of multiple modes offers an avenue through which Black women can respond to multiple forms of simultaneous oppression.

The potential for the multiplicity inherent within multimodality to enhance agency is further highlighted if we turn to the concept of synesthesia – the process whereby one mode stimulates a sensation typically associated with another mode. Specifically, if we consider Kehinde’s use of photographs alongside the auditory components of the album, we can recognize the potential for the visual to amplify the voices of Black women and complicate hegemonic understandings of their experiences. Robin Small-McCarthy (1999) describes synesthesia as a “transmodal” experience that can “evoke auditory images” (p. 176), and I find this description especially applicable to A Woman’s Reprieve. More specifically, the photographs in the print insert exist alongside the aural sounds that are spoken and sung on the album. Not only can we can see the photo representations of Kehinde’s story, but we can also listen to Kehinde’s journey throughout the album. As a result, the photos are no longer strictly visual stimuli. Instead, they become aural stimuli, what we might think of as “auditory images” (Small-McCarthy, p. 176). The woman in the photos is not just a visual representation of a Nigerian American woman. Rather, as a result of the multimodality of A Woman’s Reprieve, the combination of visual and aural modes, we have heard Kehinde’s voice, her sobs, and her exclamations; we have seen photos of her and her family. Consequently, we can appreciate Kehinde as more than a photo; she is a living, expressive individual. She is Kehinde Spencer, a Nigerian woman with a particular story of heartbreak and growth that is both seen and heard.

Additionally, the ability to combine multiple modes in a single text is an especially productive means of enhancing agency when we consider the fact that agency “always take[s] place within a field of power relations” (Gardiner, 1995, p. 10). As Foucault makes clear, power is not a fixed entity; it is constantly in flux. Power is “produced and enacted in and through discourses, relationships, activities, spaces, and times by people as they compete for access to and control of resources, tools, identities” (Moje and Lewis, 2007, p. 17). The fluid nature of power, although it renders oppression systemic and unpredictable, also offers a source of agency. That is, by making purposeful and rhetorical use of discourse in constructions and representations of the self, what Elizabeth Birr Moje and Cynthia Lewis call “the strategic making and remaking of selves [and] identities” (p. 18), marginalized individuals can position themselves in a more empowering “field of power relations,” gaining access to “resources, tools, [and] identities” that might otherwise remain unattainable. As I hope this analysis has shown, Kehinde’s use of visual, linguistic, and aural modes to construct and present an identity for herself rooted in her African culture offers evidence of what this can look like in practice, of the ways in which the feminist agent can call upon multimodality to secure what Kress calls “agency of a real kind.”

Endnotes

[1] Following the lead of Elaine Richardson, I use the terms African American and Black interchangeably. Throughout this discussion, I also refer to Kehinde as Nigerian American because, although she “consider[s] [her]self Black and part of the African American community because [she] live[s] in the United States and that is the culture [she is] a part of,” she self-identifies more specifically as a Nigerian American woman (Spencer, 2016).

[2] Although conducting a case study analysis of A Woman’s Reprieve has allowed me to develop an in-depth understanding of Kehinde’s rhetorical strategies and offer potential implications regarding our understanding of multimodality and feminist agency, the case study design of this analysis also limits the generalizability of my conclusions. This research, similar to all research, is partial, “an interpretation of an already interpreted world” (Welch, Piekkari, Plakoyiannaki, and Paavilainen-Mantymaki, 2011, p. 744). Thus, I recognize that the conclusions and observations I offer are limited to feminist agency as it is practiced by Kehinde. Still, my hope is that that this analysis leads to productive insights, healthy dialogues, and future research through which we continue to explore the dynamic relationship between feminist agency and multimodality for African American women.

[3] All photos and quotes from A Woman’s Reprieve are used with permission from Kehinde Spencer.

[4] The individual woman protagonist on A Woman’s Reprieve is never explicitly named on the album. However, since Spencer claims this story as her “story of pain and sadness,” I understand the woman to be a representation of Spencer. Additionally, in my conversations with her, she acknowledges, “I created this [woman] character for me; I was talking about me. […] I told my story of the heartbreak through her story of heartbreak. [Although] I didn’t have a relationship with a married man, the struggle of heartbreak is the same, [and] I became the character within the text by using my [personal] photos” (Spencer, 2015). Therefore, for the sake of clarity throughout this discussion, when I refer to the album’s protagonist, I call her “Kehinde.”

[5] In “Sound Matters: Notes Toward the Analysis and Design of Sound in Multimodal Webtexts” (2006), Heidi McKee offers six elements of vocal delivery: tension (how tight or strained), roughness (how raspy or throaty), breathiness (how airy or intimate), loudness (how booming or soft), pitch (how high or low), and vibrato (how trembling it sounds).

References

Bádéjo, D. (1998). African feminism: Mythical and social power of women of African descent. Research in African Literatures, 29(2), 94-111.

Banks, A. (2011). Digital griots: African American rhetoric in a multimedia age. NCTE.

Banner, D. [DavidBannerVEVO]. (2009, October 8). Like a pimp ft. Lil’ Flip. [Video file.] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MKGQ5cIw_ew

Bromley, V. (2012). Feminisms matter: Debates, theories, activism. University of Toronto Press.

Carey, T. (2012). Firing Mama’s gun: The rhetorical campaign in Geneva Smitherman’s 1971-73 essays. Rhetoric Review, 31(2), 130-147.

Chepp, V. (2012). Art as public knowledge and everyday politics: The case of African American spoken word. Humanity & Society, 36(3), 20-250.

Collins, P. H. (1993). Toward a New Vision: Race, Class, and Gender as Categories of Analysis and Connection. Race, Class, & Sex, 1(1), 25-45.

Fierce, Tasha. (2015). Sister soldiers: On Black women, police brutality, and the true meaning of Black liberation. Bitch, 66, 29-32.

Flag of the UNIA. (2009). Wikimedia commons. Retrieved March 21, 2015, from www.commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_the_UNIA.svg

Friedman, S. S. (1995). Beyond white and other: Relationality and narratives of race in feminist discourse. Signs, 21(1), 1-49.

Gardiner, J.K. (1995). Introduction. In J.K. Gardiner, Provoking agents: Gender and agency in theory and practice (pp.1-18). USA: University of Illinois Press.

Gonzalez, M. M. (2008). Feminist praxis challenges the identity question: Toward new collective identity metaphors. Hypatia, 23(3), 22-38.

Grace, C. M. (2004). Exploring the African American oral tradition: Instructional implications for literacy learning. Language Arts, 81(6), 481-490.

Hibbert, L. (2009). Tracing the benefits of multimodal learning in a self-portrait project in Mitchell’s Plain, South Africa. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 27(2), 203-213.

Kress, G. (2000). Multimodality: Challenges to thinking about Language. TESOL Quarterly, 34(2),. 337-340.

Lhooq, M. (2014, August 23). Shocked and outraged by Nicki Minaj’s Anaconda video? Perhaps you should butt out. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/womens-blog/2014/aug/22/nicki-minaj-anaconda-video-black-women-sexuality

Littlefield, M. B. (2007). Black women, mothering, and protest in 19th century American society. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 2(1), 53-61.

Lorde, A. (1984). Sister Outsider. The Crossing Press.

McKee, H. (2006). Sound matters: Notes toward the analysis and design of sound in multimodal webtexts. Computers and Composition, 23, 335-354.

Moje, E. B, & Lewis, C. (2007). Examining opportunities to learn literacy: The role of critical sociocultural literacy research. In C. Lewis, P. Enciso, & E. B. Moje (Eds.), Reframing sociocultural research on literacy: Identity, agency, and power (pp. 15-48). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Nykol, A. (2015). Blacks representation in the media. The New Black Magazine. Retrieved from www.thenewblackmagazine.com/view.aspx?index=176

Pan-African Flag. (2015, February 8). Wikipedia. Retrieved May 15, 2015, from www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pan-African_flag

Patton, T. O. (2006). Hey girl, am I more than my hair? African American women and their struggles with beauty, body image, and hair. NWSA Journal, 18(2), 24-51.

Peterson, C. (1995). “Doers of the Word”: African-American women speakers and writers in the North (1830-1880). Oxford University Press.

Richardson, E. (2002). “To protect and serve”: African American female literacies.” College Composition and Communication, 53(4), 675-704.

Royster, J. J. (2006). Responsible citizenship: Ethos, action, and the voices of African American women. In P. Bizzell (Ed.), Rhetorical agendas: Political, ethical, spiritual (pp. 41-55). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Small-McCarthy, R. (1999). From “The Bluest Eye” to “Jazz”: A retrospective of Toni Morrison’s literary sounds. Counterpoints, 96, 175-193.

Spencer, K. (2008). A woman’s reprieve [CD]. N.p.: Elevated Expressions.

Spencer, K. (2015, March 1). Personal interview.

Spencer, K. (2016, August 15). Re: Hi Esther! A woman’s reprieve article. Email.

Wang, C., Burris, M. A., & Ping, X. Y. (1996). Chinese village women as visual anthropologists: A participatory approach to reaching policymakers. Social Science & Medicine, 42(10), 1391-1400.

Welch, C, Piekkari, R., Plakoyiannaki, E, & and Paavilainen-Mantymaki, E. (2011). Theorising from case studies: Towards a pluralist future for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), 740-762.