Themed Issue: Invisible Labor in the Academy, Fall 2020 [Update: Submissions now due 9/15]

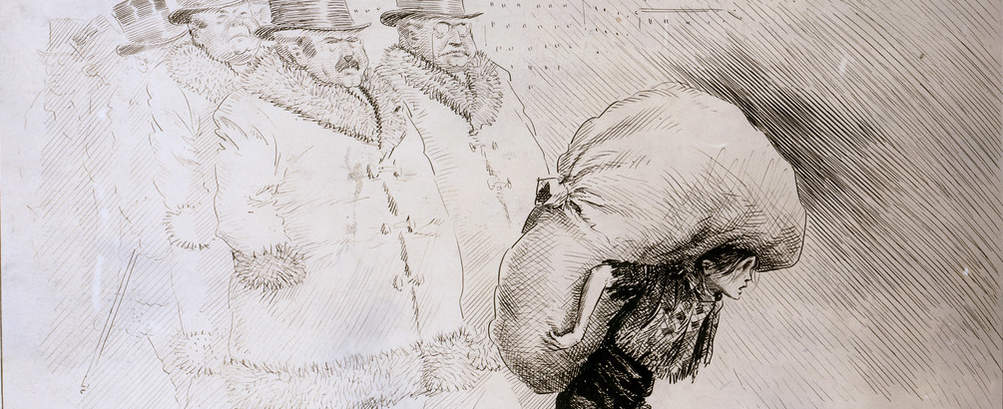

"The Road to Dividends" by TAD, ca. 1913

Academia relies heavily on labor that goes unrecognized. Those who perform such work are typically undervalued and, too often, underpaid if they receive compensation at all. Contingent faculty feel pressured to do more work for less pay to ensure contract renewal. Graduate students feel they must outperform their predecessors and peers to secure employment in the current job market. Untenured faculty take on additional service and research to prove they deserve their tenure and promotion. Success in these areas may be deemed stellar but not necessarily acknowledged as extra. At all levels, people’s physical and mental well-being is being affected. At all levels, people are being forced out.

Women and members of marginalized groups are hit especially hard by academia’s high demands for invisible labor. Eve Tuck and K Wayne Yang make clear who suffers most under this labor regime.

Universities make public commitments to effective sexual violence policies, to diversity, to “indigenizing,” to welcoming more Black faculty and students, to improved gender diversity policies and supports; yet, it is clear that they can’t possibly do this without the already overburdened presence of people of color, sexual violence survivors, Black people, queer people, nonbinary people, gender-nonconforming people, and Indigenous people (of course, these are not mutually exclusive peoples!). Universities that herald these needed changes as part of new and emerging definitions of excellence thus are legitimated by the presence of those who have historically been systematically and purposefully excluded; indeed, those upon whose backs entire disciplines have been forged. (2018, p. 2)

Women are expected to nurture students, not just teach them; center research rather than family; and even self-regulate their appearance lest they be accused of lacking in professionalism (Chenoweth et al., 2016). Sexist expectations intensify the conditions of racism, creating the “revolving door” of academia that claims the careers of many women of color, especially Black women, when editors and tenure committees decide their research is either not scholarly enough or not universally applicable (Billngslea Brown, 2012, p. 27). Native scholars must learn and work in institutions that erase these universities’ complicity in settler colonialism, displacement, and genocide, compelled to continuously remind others that prestigious schools have gained their reputations through dispossession and the sale of Native lands (Landry, 2017). Every day, BIPOC scholars are forced to perform the “emotional work of diversity work,” foisted on individuals by institutions that pledge their commitment to diversity but do nothing to effect real material and ideological change (Ahmed 2009, p. 43). This “insidious and invisible economy of service” makes people choose between health and professional advancement (Hogan, 2010, p. 55), a choice that can severely compromise disabled people’s safety even if accessibility were not a major problem on campuses everywhere (Davis, 2015). Queer, trans, nonbinary, agender, and gender nonconforming teachers and students must expend vital energy responding to different forms of bigotry (see Evans, 2017). The list goes on and on, especially when one considers the impact of interactive -isms and -phobias on those who are multiply marginalized.

Tuck and Yang argue that the term “invisible labor” doesn’t adequately describe the work imposed on marginalized people since the labor itself is evidenced in the institution’s ability to function. However, bringing to bear Adela C. Licona’s work that highlights invisibility and visibility as power-full and constructed conditions (2005; 2014), this issue deliberately draws on the tensions present in the term “invisible labor.” The term itself can draw attention to or distract from particular concerns, include or exclude different kinds of work, and demand action or encourage empty virtue signaling. Authors are encouraged to consider such inconsistencies and their bearing on everyday instantiations of invisible labor. Testimonios are certainly welcome, since they can highlight the voices of marginalized people, allowing us to inscribe our experiences and strategically repurpose academic spaces and practices (Chávez, 2012). However, the author’s approach may vary.

Preferably, submissions will 1) speak to multiple forms of marginalization and/or provide critiques of the issue “from below,” 2) make use of multimodality in proving what’s at stake in these discussions, and 3) range from 2,500-4,500 words (excluding References) so that we may include as many voices as possible in one issue. Authors may address the following questions and concerns.

- What are the diverse politics of in/visibility surrounding academic labor?

- How do whitestream academic expectations regarding comportment, speech, dress, and social interactions impose additional forms of labor on students and instructors from “non-traditional” backgrounds?

- What kind of pedagogical moves must instructors from marginalized backgrounds make to be “heard” in the classroom?

- What professional risks do members of marginalized groups take to be “seen” at their institutions and in the discipline, and how can we better recognize visibility as a form of labor?

- How does the imposition of additional unrecognized labor become a vehicle for erasure and/or dehumanization?

- How do conditions of in/visibility complicate or refute traditional boundaries between academia and the “real world,” and how does that relate to invisible forms of labor?

- How do hyper-real spaces like the internet render labor invisible and who is most affected?

- What demographics and types of action tend to be ignored by discussions about invisible labor?

- How do multiply-marginalized individuals contend with unique intersections of invisible labor?

- What are the different kinds of labor demanded by micro- and macroaggressions?

- What must academia do to acknowledge and honor invisible labor at the local and comprehensive levels?

- How does the work members of minoritized populations must do to maintain vital relationships within and outside of the academy constitute invisible labor?

- What other issues do scholarly conversations about the invisibility of marginalized labor continue to ignore?

Potential authors may suggest additional topics.

TIMELINE

- Submissions due: Sept 15, 2020

- Authors notified: October 1, 2020

- Revisions due: November 20, 2020

- Publication: December 2020

CONTACT

Please email queries or questions to JOMR at journalofmultimodalrhetorics@gmail.com.