Negotiating Crip Comfort: Dispatches from My (Involuntarily) Subversive Wardrobe

Adam Hubrig, University of Nebraska—Lincoln

I hobble to the elevator to lift my bodymind from the ground level of the English Department’s building to the third, where I will soon hold mid-semester one-on-one conferences with first year writing students in my office. I—a graduate student in Composition and Rhetoric—am joined in the elevator by a senior faculty member who takes a moment to regard my outfit. “How many cat t-shirts do you even own?” he asks through something of a reflexive harrumph. He gets off the elevator before I can articulate an answer more meaningful than a shrug.

I am concerned about how my carefully negotiated clothing choices—inseparable from the rhetoric of my (white, male, disabled) bodymind-are read by students, colleagues, and administration. And like other disability studies scholars, I am interested in issues of access. Accessibility issues often manifest themselves in mundane aspects of academic work. As mundane as the often unwritten dress codes adopted by academia might seem, I argue that they are an important site for considerations of accessibility that—when interrogated—render visible concerns of privilege at the intersections of ability, race, gender, sexuality, and class. Let me be blunt: our collective notion of “professionalism” is—by design—ableist and inaccessible.

In The Professor is In: The Essential Guide to Turning Your Ph.D. Into a Job, author Karen Kelsky describes fashion “micro-practices” (2015, p. 299)—idiosyncratic tendencies within academic subfields. Here I seek to understand both a broad range of macro-practice tendencies and attitudes in academia, but particularly how these practices are informed by ableist normative values and how those rules—implicit and explicit—are cunningly transgressed by disabled folks as a form of material, multimodal composition, which highlight oppressive and exclusionary norms.

Professionalization and Crip Comfort

Calls to be “professional,” to dress up our bodies, our language, or our lives are exclusionary practices. As Carmen Rios asserts, marginalized folks “aren’t supposed to be comfortable when we’re being professional.” Rios describes her own experiences as a queer, working-class woman of color in “professional” settings, detailing how dress codes upheld power structures that were blatantly racist, sexist, classist, and xenophobic. Rios argues that “professionalism is a tool of the elite to keep workforces “in their place”–and often, that place is defined in opposition to communities of color, queer culture, and the actual working class.” While Rios’s criticisms are about the world of business, the same critiques of “professional” expectations are certainly present in higher education, expectations which deny access and comfort to marginalized folks.

For example, research considering how these concerns of academic dress are intertwined with race and identity. One study—which focused on how student responses to teaching faculty at an HBCU manifested in everything from absences to teaching evaluations—found Black professors were considered “more trustworthy” when they dressed in formal attire, and suggested White professors were considered less intimidating when dressed casually (Aruguete et al., 2017, p. 498). The researchers warn that—especially in prevailing consumer-driven models of higher education—that institutions must take it upon themselves to avoid discrimination in these instances (p. 500). While I certainly agree with the researchers, I focus here on their findings to point to how the pressure to dress in formal attire is disproportionately experienced by POC. Rhetorical negotiations of dress are certainly complicated by racial inequality and perceptions of race.

And the rhetorical negotiations of fashion choice are also entangled in conversations of gender and sexuality. In explaining her own rhetorical negotiations of dress, Holly Genovese describes clothing as “just one more minefield for female graduate students that their male counterparts do not encounter in the same way.” Ben Barry writes that—as a queer scholar—he has observed how wearing masculine clothing confers male privilege: “Understated blazers and button-downs can shield marginalized academics—whose identities would otherwise stand out as different in the university—from the discrimination that often discounts and diminishes our ideas and contributions.” Masculine formal attire has a specific connotation of male power, where simply wearing a suit and tie (or inhabiting a masculine body) comes with it unearned privileges.

And concerns about fashion choices are intrinsically connected to socio-economic class. Shahidha Bari echoes concerns about economic disparity in academia: “the harried teaching assistants of today’s university, underpaid and overworked, have neither time nor income to spare on sartorial matters. Somehow they must seamlessly segue from graduate students slumming in sneakers to professorial formality.” The combination of the expectation that academics dress professionally contrasted with the material realities faced by many academics is patently absurd, particularly as higher education relies more and more on underpaid and undervalued contingent faculty expected to dress the part of solidly middle-class professionals while being paid poverty wages.

In short, dress standards create a space for bigotry to become policy—akin to assumptions about Standard American English—that exclude already marginalized folks in the name of professionalization. In this article, I interrogate expectations for how we dress up bodies creates assumed-to-be neutral barriers for marginalized folks. Within academia, work has been done to demonstrate that unspoken dress codes exist and that the stakes are different for already marginalized bodyminds. While the scholarship I’ve described above begins to describe how professional dress expectations are compounded by marginalized identities, I am interested here about the rhetorical negotiations made by disabled folks. While I am aware my cat t-shirts and jeans might not indicate to some the careful rhetorical negotiations of dress—perhaps even communicating that I simply don’t care about my fashion choices—they are the result of a great deal of rhetorical negotiations, of bodily trial and error, and of prioritizing comfort.

I take pause to clarify comfort. Returning to Rios’s argument, marginalized people are denied comfort by calls of professionalization. I realize that within an abled purview the connotations of comfort may mean something entirely different than I intend: here, with the word comfort, I mean being able to meet ableist expectations and demands, even in crip ways. I mean those necessary adjustments disabled folks make to exist in disabling spaces. Like many other disability rights advocates, I draw on the social model of disability that explores how disability is a social construct dependent on its context. Feminist disability scholar Susan Wendell observes “Disability in a given situation is often created by the unwillingness of others to adapt themselves of the environment to the physical or psychological reality of the person designated as ‘disabled’” (1997, p. 30). Wendell goes on to describe how—for many disabled folks—the changes they make in their own lives (such as mobility devices, the daily lives of blind folks, or the ways neurodivergent people may experience conversation differently than neurotypical folks) do not seem unusual, but are quite ordinary aspects of disabled lives. I am interested in these moments—experienced as normal to the disabled person but considered unusual or an accommodation by outsiders—as potentially subversive, rhetorical acts that render the implicit oppressive norms of everyday policies clear.

I am interested in how disabled folks crip[1] the concept of comfort. And, in doing so, I hope to pinpoint a specific form of Metis that I refer to as crip comfort. Metis, as outlined by rhetorician Debra Hawhee, refers to an embodied rhetoric dependent on hexis, a Greek term denoting the condition of the body (58). These concerns of embodied rhetoric, of metis, become a central concept for Jay Dolmage in his work theorizing disability rhetoric. Drawing on differing accounts of both the myths of the Greek goddess Metis as well as other rhetorical traditions as articulated by scholars Helene Cixous and Gloria Anzaldua, Dolmage traces how feminine bodies have been historically pathologized and how disability and disease are key metaphors in understanding embodied rhetoric (2009, p. 3). Dolmage traces the selective embodied rhetorical traditions in which the body is stigmatized and perceived as the antithesis of knowledge, rather than the rich rhetorical traditions which point to the body as a source of knowing and knowledge. Dolmage locates the construction of disability within rhetoric, and suggests “that we might respond to this oppressive legacy by using our bodies significantly and making rhetoric significantly bodied” (p. 4). While his rhetorical and historical scholarship on the subject of metis offers contested meanings and possibilities for embodied rhetoric as metis (2014, p. 6), I focus on crip comfort as a specific practice of metis that becomes necessary when we create barriers that deny comfort, when we subscribe to professional standards that are inherently exclusionary to already marginalized bodyminds.

I claim crip comfort as a form of multimodal composing, echoing Katie Manthey who argues “the construction of my identity through manipulating clothing is an example of multimodal composition” (2015, p. 340). But I focus on how certain categories of identity, certain kinds of bodyminds, are incompatible with “professional” expectations: Precisely because of professional expectations—and not because my bodymind is inherently deficient—my bodymind is unprofessional. In an effort to meet the needs of my unprofessional bodymind, my wardrobe is unprofessional, too. While I realize my crip comfort wardrobe choices may seem odd and idiosyncratic to others in the field—and certainly to many in my own department—these are carefully negotiated tactics of crip comfort that enable me within an otherwise disabling context. I hope that in allowing access into these rhetorical negotiations and practical considerations I often choose to conceal, I might better articulate a working theory of crip comfort.

Crip Comfort Redux: A Tour of My Disabled Wardrobe

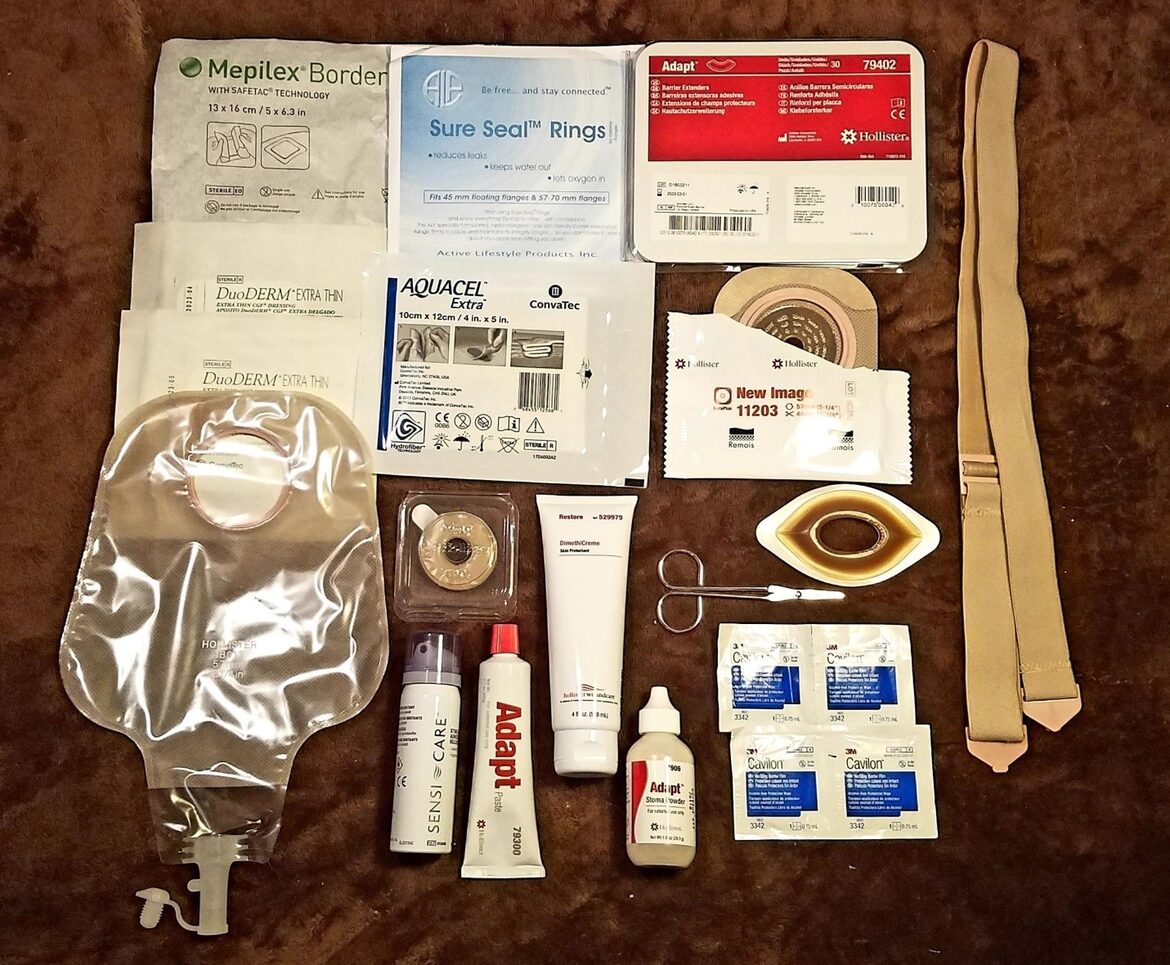

Our tour begins with the fashion accessory to which most of my closet space is devoted: my colostomy supplies. For those of you lucky enough not to know, a colostomy device serves as an artificial colon: a tiny nub of small intestine (called a stoma) protrudes from my belly and empties (gas, fecal matter, and—because of an intestinal disorder—blood) into the bag. The assembly is connected by a wax seal and fixed to my abdomen by medical adhesive.

My days are planned around my colostomy, knowing at all times where the nearest bathroom is should my colostomy bag fail and I need to change it. I have at least three sets of colostomy gear in my bag with me when I leave home each morning, and another half-dozen sets ready to go in an office storage bin. Should this device fail—and it frequently does, as its “medical science” is basically a glorified Ziploc bag held in place by sticky putty and off-brand duct tape—I have no control over these bodily fluids erupting everywhere. This unfortunate, unprofessional occurrence takes place at professional functions of all stripes, like in my classroom, in faculty meetings, and at academic conferences.

This single medical necessity dictates a large portion of my wardrobe choices. For instance, the seemingly ubiquitous professional fashion advice (usually directed at those who identify and present as masculine but sometimes at feminine-presenting, genderqueer, and non-binary folks, too): “tuck in your shirt and wear a belt.” I understand how this seems to be a fairly simple thing to do. But tucking in my shirt is to guarantee my ostomy device will fail. And despite the fashion advice, I’d rather have a shirt not tucked in than one soaked with feces and blood.

I mostly wear jeans, the kind that are made of elastic, stretchy fabric, and even then jeans that are quite loose. As if the blood and feces conversation wasn’t unprofessional enough, let’s talk about incontinence: it’s hard to hide the outlines of adult diapers under any form of dress pants. I prefer to conceal that I’m wearing an adult diaper if I can, as that particular item of clothing seems to be considered very unprofessional, even connected to incompetence. I’m reminded of the protest against “safe spaces” staged by members of Turning Point USA—the group perhaps best known for their fascist professor watchlist—where a protestor wore a diaper (Shugerman, 2018). Though I passionately disagree with the argument against trigger warnings and safe spaces the protest was trying to make, I can’t help but internalize that my daily existence requires me to rely on this same piece of clothing their demonstration used to denote incompetence.

|

|

|

But my stretchy jeans are also connected to another part of my disability: the uncontrollable variance in weight and shape of my body. During the past four years of my PhD studies, my weight has oscillated from 150 lbs. to 310 lbs. Despite what assumptions people might have about weight and health (and the frustration of having so many well-meaning people approaching me, while my health was failing at 150 lbs., to tell me how much better I looked), I was much healthier at 310 pounds than 150 pounds. Having clothes that can accommodate weight changes—even flexible fabric that can accommodate changes of several pounds in a week or severe bloating and distension in the course of a day due to a blockage—is important.

As my disability has become increasingly visible, I’ve shifted from button down shirts to print t-shirts. Besides the lowered expectations that t-shirts be tucked in and how the edges of my ostomy seem to get caught up in the buttons, some of my medical apparatus (the ostomy supplies and wound dressings) create awkward protrusions under my clothing: visible lumps and odd curves. When I’m wearing a print t-shirt with cats or Nintendo characters or disability advocacy prints, I can at least try and let myself believe when that when my torso elicits long stares from people—family, students, colleagues, strangers—that they are staring at the boxing cat, Majora’s Mask, or “Disability Justice is Love.” I am too-well aware that they are not staring at the cat shirt when their facial expressions convey disgust, but at least I can feel less alienated by pretending they are.

|

|

Figure 2: Except clean water and paper towels, this image represents everything I need for a single change of my colostomy and related wound care. |

But the tees are also important because I can change them in about three seconds. This is no clumsy estimation or exaggeration. I have the entire process of changing my outfit and ostomy assembly carefully practiced and timed like a one person NASCAR pit crew. I feel the weight of each passing second when a colostomy bag fails and I need to duck out while teaching a class, attending a meeting, or taking part in other professional functions because of my unprofessional body.

|

|

Figure 3: Some of my favorite printed tees to wear while teaching: my “Feminist Fight Club” shirt, a shirt featuring Nintendo’s “Majora’s Mask” designed by Spanish graphic designer Paula Garcia, and a shirt reading “RESIST” (the word RESIST signed in American Sign Language) ABLEISM from disability rights activist Imani Barbarin’s Patreon store.

|

|

|

Figure 4: Me sporting a handmade colostomy bag cover made by my partner. This one features an arrangement of postage and letters. |

But it’s not just the colostomy that’s unprofessional: The joy of autoimmune disorders is that they often impact multiple bodily systems. It also grants me psoriatic arthritis. It’s hell on my knees. That’s why this 30-year-old academic is rocking the same orthopedic inserts as his 93-year-old great-grandmother (true story). I grow out my beard to cover the psoriasis on my face and down my neck. When the psoriasis gets intolerable on my scalp, I wear a baseball cap to conceal the symptoms up top.

I close this tour of my wardrobe by touching on my favorite accessories: my ostomy covers. I hate the ostomy device as a whole; it’s messy. There is no voluntary muscle control with an ostomy, and so I have no control over when the nub of intestine protruding from my belly will empty into the ostomy pouch. It happens when I’m teaching, when I’m speaking with a colleague, when I’m presenting at conferences. It’s not a big deal, but without the covers it may be visible. The covers—lovingly homemade by my partner to fit the exact sized ostomy pouches I need—hide it. And, like my t-shirts, they feature prints of all kinds of things I enjoy, so when people stare, I can choose to believe they are staring at Pokemon or bees.

This brings me to how the rhetoric of my wardrobe may be read--as if I my wardrobe choices are simply laziness. I will not soon forget the moment during my graduate coursework when the professor teaching the class singled me out by asking a peer the hypothetical question while pointing to my body “if you were the chair of the department, would you let Adam teach dressed like that?”

Any number of positionalities might influence the wardrobe choices of any unique bodymind. That they would choose to dress “like that” for any number of reasons—our colleagues may choose adaptive clothing to be more comfortable in a wheelchair, they may choose to wear seamless garments to meet their sensory needs, or build their outfit around a colostomy bag.

Dressing for crip comfort, I do teach dressed “like that.” And it would seem dressing “like that” demonstrates there are expectations, there are boundaries being crossed. And this imposition of normative dress policies is to create a barrier, to say which kinds clothing and the bodyminds wearing them are welcome in higher education.

Getting Away with Crip Comfort

In establishing the dress expectations of women, Genovese articulates the gendered standards of implicit dress codes in academia, stating: “male graduate students often get away with casual dress in the classroom that would not go over well for women” (2017). I in no way express disagreement with Genovese or her experiences, and have witnessed these same gendered dress expectations in higher education, particularly as I mentored first year graduate teaching assistants navigating fashion choices. I understand that, in this context, male privilege is certainly what allows the getting away with, just as white or cis or other normative privileges may enable it. But I want to focus on the phrase get away with.

Get away with suggests subversion. It suggests that there was a rule, a standard, an expectation that was sidestepped, avoided, or cunningly overcome. To get away with suggests transgression of an established norm. In his book outlining precisely the ableist nature of higher education, Dolmage argues that “accessibility itself is [. . .] existentially second to inaccessibility. Accessibility is existentially second in a way that demands a body that cannot access. Nothing is inaccessible until the first body can’t access it, demand access to it, or is recognized as not having access” (2017, p. 53). Crip comfort is a rhetorical intervention, it is demanding access by making the ableist policies—implicit and explicit—clear. While simultaneously entangled with and inseparable from race, gender, class and other social concerns, crip comfort as a rhetorical intervention is a form of sidestepping, a kind of “getting away with” or bending expectations.

But in getting away with a different form of dress, crip comfort makes clear not only the absurdity of implicit professional dress standards (should it matter which fabric covers my hide?), but how they are both unnecessary and oppressive. Approaching concerns of professionalization (and other matters of policy) through crip comfort highlight oppressive, ableist expectations. Margaret Price and Stephanie Kerschbaum, for example, challenge normative research practices in higher education, pointing to how “disability crips methodology” (2016, p. 20). The authors point to their own choices as researchers with disabilities and how “when disability is assumed to be an important part of the qualitative interview situation [. . . ] the interview’s normative framework is exposed and challenged” (2016, p. 20). Thinking about another facet of academic culture, Price describes how institutions might better think through job market interviews and campus visits. She points to the experience of a woman, Clarice, who has Asperger's. Her presence in the interviews highlights how the process is designed for neurotypical people (2014, p. 118). These are other forms of crip comfort, of the rhetorical negotiations of disabled bodyminds subverting ableist expectations.

Of course, a department allowing an instructor to dress against the grain, of doing interviews or conducting research in an atypical manner, or thinking through accessibility issues for campus visits may be considered an accommodation. Accommodations create the same sort of division Sharon Snyder and David Mitchell describe in terms of charity (2015, p. 56)—a parasitic relationship where disabled folks should be grateful instead of addressing systemic oppression.

As such, this framework of accommodations puts the onus of accessibility on disabled folks. Consider this reflection on the matter by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarashinha, who writes about accommodations as a disabled woman of color, highlighting how accommodations are even more fraught for at the intersections of marginalization:

It was unsafe for me to say that I might need a tutor—tutors and accommodations, newly allowed under the brand new ADA, were for the rich white boys; I just had to be twice as smart if I wanted to get a scholarship. I couldn’t afford to look “stupid.” [. . . ] Some of our needs were so vulnerable, so embarrassing, so complicated to ask for that it was much easier to just not admit we needed them. (2018, p. 56-57)

Crip comfort resists being an accommodation because accommodation belong to institutions and are born from a particular kind of neoliberal logic. Stephanie Kerschbaum describes neoliberal trends in higher education as they relate to diversity logics rooted in marketability, arguing that “such diversity discourses make it difficult to identify or alter systematic practices that legitimate oppression and disenfranchisement” (2014, p. 39). Similarly to these institutional diversity efforts, the language of accommodations positions the institution as the gracious host and disabled folks as reliant on their institutional charity. Instead of an accommodation, crip comfort is a rhetorical intervention which lays bare institutional ableism and created inaccessibility.

But while disabled folks may get away with one form of crip comfort or another in that we are “allowed” to do it, I don’t mean to imply that crip comfort comes without consequence. I have not been outright punished for my crip comfort fashion choices, and I recognize this is likely because of a convergence of white, male privilege. But I have been approached by more than one colleague who has told me to dress more professionally—one even commenting that my ostomy bag was “inappropriate” in my classroom and academic settings (as if I could just choose not to wear it). For others, the consequences of crip comfort have been much more dire: in an altogether different professional context, Barbarin recounts how—because of disability—she wore sneakers to a job interview in an inaccessible building. “I look around the room and see beautiful girls wearing heels that perfectly complement their outfits. I’m in sneakers that make me stick out. And then there’s the crutches, which gleam like a neon sign saying 'I’m expensive'” (Barbarin 2019, p. 113), The interview Barbarian describes is both a nightmare and the lived reality of many disabled folks: the interviewer being visibly shocked upon seeing her, the motivational poster on the wall reading “The only disability in life is a bad attitude,” and the interviewer condescendingly responding “good for you” to her accomplishments.

|

|

Figure 5: A #TheCostOfBeingDisabled tweet by @Aoiferocksitout.

|

|

|

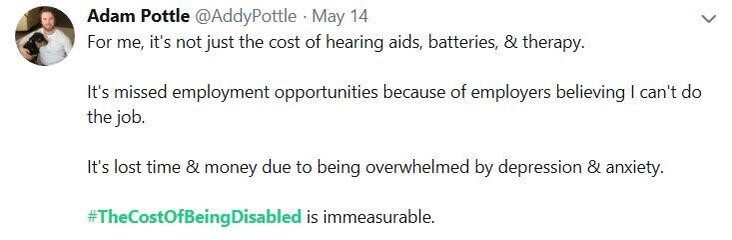

Figure 6: A #TheCostOfBeingDisabled tweet by @AddyPottle.

|

|

|

Figure 7: A #TheCostOfBeingDisabled tweet by @SFdirewolf. |

A full range of the material realities of disability, often the result of ableist norms, is on display through the hashtag #TheCostOfBeingDisabled, which was also created by Barbarin and shares its name with her article. The hashtag captures several stories by disabled folks who have paid dearly because of oppressive ableist norms, but in voicing what was lost, it also makes clear the social expectations that disabled people transgress. Disabled folks shared stories of losing employment opportunities, being unable to have monetary savings because of how disability income regulations are structured, and having friends and loved ones abandon them because they couldn’t meet social expectations.

These moments, these snapshots of the lives of disabled folks demonstrate crip transgressions against ableist culture, the social spaces that exclude certain bodyminds. In short, these tweets highlight the policies and attitudes that are disabling.

In trying to further understand the role of the body in rhetorical tradition, Dolmage turns to the mythology of Hephaestus:

a Greek god who embodied metis, the cunning intelligence needed to act in a world of chance [. . .] His body was celebrated, not despite his body, but because of his embodied intelligence. Hephaestus story has been neglected, but we can now read it as a challenge to stories that reinscribe normative ideas about rhetorical facility and about which bodies matter. (2014, p. 151)

While the lives and experiences of disabled folks have certainly been neglected, even ignored, I argue that the embodied intelligence of crip comfort as a specific form of metis serves to normative ideas and ableist ideologies. The rhetorical navigation disabled folks master to “get away with” having bodyminds “like that” in public productively disrupts notions what is professional and which bodyminds can be and have been considered professional. From implicit dress codes to interview ethics to how campus visits are conducted, crip comfort challenges ableist attitudes both within and outside of higher education.

References

Aruguete, M., et al. (2017). The effects of professors’ race and clothing styles on student evaluations. The Journal of Negro Education, 86(4), 494-502.

Barbarin, I. (2018, 15 May). The cost of being disabled. Good Company. Retrieved from https://www.designsponge.com/2019/05/the-cost-of-being-disabled-imani-barbarin.html

Barnes, E. (2018). Minority body: A theory of disability. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Bari, S. (2017, 27 August). What we wear in the underfunded university. Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/What-We-Wear-in-the/240986

Dolmage, J. (2009). Metis, mêtis, mestiza, medusa: Rhetorical bodies across rhetorical traditions. Rhetoric Review, 28(1), 1-28.

Dolmage, J. (2014). Disability rhetoric. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Dolmage, J. (2017). Academic ableism: Disability and higher education. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Genovese, H. (2017, 28 September). Cute outfits and the academic career. Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/Cute-Outfitsthe-Academic/241309

Kelsky, K. (2015). The professor is in: The essential guide to turning your Ph.D. into a job. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press.

Kerschbaum, S. L. (2014). Towards a new rhetoric of difference. USA: National Council of Teachers of English.

Manthey, K. (2015). Wearing multimodal composition: The case for examining dress practices in the writing classroom. Journal of Global Literacies, Technologies, and Emerging Pedagogies, 3(1), 335-343.

Price, M. (2014). Mad at school: Rhetorics of mental disability and academic life. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Price, M., & Kerschbaum, S. (2016). Stories of methodology: Interviewing sideways, crooked and crip. The Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 5(3), 18-56.

Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. L. (2018). Care work: Dreaming disability justice. Vancouver, BC: Arsenal Pulp Press.

Rios, C. (2015, 15 February). You call it professionalism; I call it oppression in a three-piece suit. Everyday feminism. Retrieved from https://everydayfeminism.com/2015/02/professionalism-and-oppression/

Shugerman, E. (2018, 26 February). Turning point USA: How one student in a diaper caused an eruption in the conservative youth organization. The Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/diaper-turning-point-usa-kent-state-student-conservative-youth-repulican-kaitlin-bennett-a8230021.html

Snyder, S. L., & Mitchell, D. T. (2015). Cultural locations of disability. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Wendell, S. (1997). The rejected body: Feminist philosophical reflections on disability. London, UK: Routledge.

[1] Here I echo other disability activists in the use of “cripping,” reclaimed from the derogatory “cripple.” For more on this, I point you to the work of Carrie Sandhal, who examines the intersections of crip and queer identities in Queering the Crip or Cripping the Queer? Intersections of Queer and Crip Identities in Solo Autobiographical Performance."