“These are the conditions we write under”: Selfies, Care-work, and Collaboration in the Time of COVID

Nikki Fragala Barnes and Farrah Cato

Keywords: collaboration, friendship, selfies, care-work, COVID

Categories: (De)Constructing Writing; Building Community in Isolating Times

I set a goal to write 300 words in three hours—not hard words, just words about my research. Then: let the dogs out and cats in; my elderly mother calls, worried I have another migraine because we haven't spoken in two days; texting with my sister to arrange baby- and pet-sitting swaps during her move to a new home; emails from students about their own challenges; emails from colleagues urging completion of Doodle polls; emails from the faculty union urging us to keep up the good fight. I owe work to my students and to my professors. Three hours later, I have 128 words on the screen. My puppy needs another potty break.

Nora barks:

These are the conditions we write in.

Nikki and I have tried to collaborate for nearly a year. This project, for this journal—this is one that speaks to our hearts and seems doable. It is about carework and all it contains, and there are so many things we care about. We will connect at 10:00. Then: my puppy; her family; my students; her internship. We both have assignments due this weekend. Can we meet at 3:00 instead? Or 4:00? We finally connect, have just enough time to encourage each other, and then: repair people arrive; a quarantined son is hungry. The phone rings. Another potty break.

Nora’s squeaky toy (33 seconds):

These are the conditions we write under.

It's not that these things never happened before COVID-19. We were just not as bone- and mind-weary then as now. Before, we could go home, or go out, or go to work. Now, everything happens simultaneously in our homes, and there is no place for respite. Who has the time to sit down long enough for a coherent, writeable thought to emerge? Who has time to make meaningful art? To even think it in these conditions, to make that kind of time when people are dying and sick and our families need us, feels selfish.

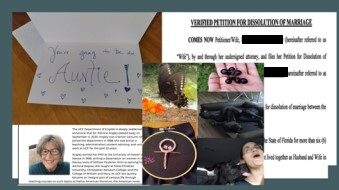

An unconventional selfie, documenting things I felt deeply: the loss of a dear friend and mentor; my nephew’s birth; marriage dissolution; some moments of joy.

And yet, miraculously, somehow we do it. Not always elegantly, but we manage. Audre Lorde insists that "poetry is not a luxury," but is instead a "vital necessity of our existence" (1984, p. 37). Alice Walker gives us her mother's garden, a reminder that our art—genuinely, urgently, desperately needed no matter what conditions we face—takes many forms.

Nikki starts our work: she takes our notes and makes them sing. I am inspired to dive in, too, when I see what she has done—after puppy’s next potty break. Her words remind me to look for other moments of “carework” over the past year, and I find them: not only in care for others, but in self care, too.

Nora video: “Go out again??”

What does it mean to live, write, and make art during a pandemic? It is messy, fragmented, and somehow, still always beautiful even in its imperfect, in-progress state(s). In reflecting on the life of Phillis Wheatley, Walker says: "[i]t is not so much what you sang, as that you kept alive […] the notion of song" (1983, p. 237). Our selfies, glimpses of what it means to live, love, work, and make art in the midst of a pandemic, are not intended as self-indulgent evidence of hardship (or not only that). Rather, these selfies are our ways of documenting what happened, of putting these fragmented pieces together, and of inviting others to recall that "notion of song," that "vital necessity" that reminds us of who we are and how we might yet live again.

These are the conditions we write under.

We believe the kind of layered, complicated work located among sites with blurred boundaries is necessary, increases vulnerabilities, and leads us to insightful, connected work that advances how we free each other and free ourselves.

We are scholars of making, of memory, of historically excluded communities and methods. Our languages are the languages of words and threads, digital strings, and conceptual material.

By staying with the struggle—deciding to make our own spaces among impossible circumstances that only become more impossible—we hold space for others. We understand our choices. And we have chosen the struggle and the impossible instead of forsaking the tasks that heap and shift.

This is not a capitalist narrative of grit and resilience. It is a record of failures and discoveries. It is the evidence of our commitment to ourselves, each other, the meaning, and the work.

Invoking our ancestors, known and unknown, answering and calling on Hillel the Elder: If not now, when? If not us, who?

Considering the rebelliousness of the selfie, the insistence of presence, of evidence of existence, of showing up in the frame, we observe the selfie albums in our handheld smartphones as a recorded archive of time fractured and divided—and then quilted.

One week in August 2021, from the last days my oldest spent at home, moving him into his first dorm, retreating to the coast and then beginning a new multimodal semester on/off campus. (Credit: Nikki Fragala Barnes)

The tectonic collisions that create ridges of our adjacent identities cannot adequately express what it feels like on the inside. Our interiors are storm-ridden—the mother who has lived with us for seven years and the relief of moving her to assisted living compounds with the emotional labor of guiding her through the transition, while my brother weighs his own accounting of my life’s offering in so many dollars and hidden burdens. By his valuation, I come up short.

One kid in college. One in high school. One in middle school.

One moves out to live on campus. One attends class in person. One remains home in virtual school.

One is already sick. Eight COVID tests (among us) in less than a month. None positive. At least a week of school and work missed.

In my fourth semester of a PhD program, I add an external internship, a conference proposal (waiting), a mentorship (accepted), a panel talk (invited), and an art installation (solicited). This is the work I seek out. It is how I am able to show up for my family without feeling trapped, martyred, wasted.

It’s 8:49 at night—a Friday night. I’m coughing. Do I need another C19 test? I have nineteen books on my desk for this semester’s work. Tomorrow I will build the set for an art installation. Code in Python. Read about history and material culture. Try to drink enough and take extra Vitamin C. Find a crevice to work on this article again. I tell myself I won’t compromise on sleep. I wear a mask in my home, in my room. I tell my youngest we can watch Come From Away so I can cry about a twentieth anniversary that did not bear the fruit we were promised. I still have to comment on 36 poems from my students, thirsty for my response, as I thirst for their insights and am refreshed by the surprises in their language. Tomorrow, or maybe Monday. There’s no such thing as balance.

Another week begins. Summer is finally ending. The evidence and effectiveness of these collapsing compartments of carework—caring for our work, our people, our selves, our communities—is not assured. It is so much planting and gardening, happening in the dark, combining compost and soil, and gentle and violent processes of life cycles. And, still, irrefutably, this attending-to is its own testament to the worth of this writing, to the work while we half-life our resources into near-oblivion. And yet, not oblivion. Something remains. At each moment of reevaluation, when I lay everything back on the table and tell myself I can walk away from anything—to decide what stays on my plate—I decide (again!) to open this document and layer more language onto a page. I decide to keep the list of eight things I must do today between my museum hours and my class hours. I choose to text my youngest son that we will watch a movie and curl up on the couch together later in the week. I email my brother that the conversations with the elder law attorney can be at the convenience of his schedule, and I’ll adjust what needs adjusting. I pull my curation readings into one file so I can read them while I’m waiting in the car for my high school kid. I make a cup of tea. When I close this document, I’ll return to researching: What is the work of museums? What is the role of / and the methods of advocacy and contributing to the work of equity by building arguments in exhibitions? I hope so many things. I go on. This work—call it critical making or creative / transdisciplinary research or co-creation—of making a life, a family, a body of work—it shapes me as I shape it / them. And I know with the compass in my bones and fibers, it matters. Fruitless or not, it matters.

References

Lorde, A. (1984). Poetry is not a luxury. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Crossing Press.

Walker, A. (1983). In search of our mothers’ gardens: Womanist prose. Harcourt Brace & Co.

Bio

Nikki Fragala Barnes (@bynikkibarnes) is a critical curator and scholar of texts and technology. Barnes’ work, collaborative and participatory, is centered on restorative research and critical making applied to media, culture, and society. Also an installation artist and experimental poet, Barnes is an instructor of Creative Writing at the University of Central Florida. Barnes' work appears in the Journal of Motherhood Studies and is forthcoming in the Surface Design Journal. They presented research this summer at the International Society for Textual Scholarship, the 8th World Conference for Women’s Studies, the Association of Academic Museums and Galleries, and Console-ing Passions, International Feminst Media Studies.

Farrah Cato is a Senior Instructor in English at the University of Central Florida where she teaches courses in Women Writers of Color, Magical Realism, and American and World Literature. She is also a doctoral student in UCF's Texts & Technology PhD program, where her research interests include critical making, women’s material culture, and women’s textiles and craft work as technologies of resistance.