Carefully Crafted: Making as Facilitator of Multimodal Composition in COVID-19 Carework

Rosanna Vail

Keywords: crafting, cardmaking, paper arts, journaling

Categories: Bearing the Weight of Racism through Anti-Racist Work and (Cross-)Racial Solidarity; Arting/Crafting/Making in a Crisis

In Hawaiʻi, where I’m from, the word kokua appears in everyday speech and public signage. Both a noun and verb, the word’s translation is “help,” but its deeper cultural meaning describes a lifestyle of coming together in self-sacrificial care and kindness toward others—mutually meeting a need simply because there is one. Kokua is both doing carework and being careworker, taught when we’re young and practiced for life. It’s instinctive, ingrained. It’s us.

One paragraph written, and I’m already unraveling—homesick, uncertain, sad. The unyielding visceral responses during the COVID-19 pandemic baffle me as I now live apart from the place of my roots, in a mainland culture that has largely demonstrated, even amidst global health crisis, an instinct and value system quite antithetical to my own. We, as humans, are still so incapable of taking care of each other, not always because of what we can or cannot do but because of what we are or are not willing to do. What will make us do what it takes? What will cause us to listen and learn and make space for voices the world needs to hear, ones with approaches grounded in anything else but what has been happening?

We are right here. We speak, we write, we create. Sometimes we shout. We share. We kokua. Or at least, we are trying.

As an important clarification before going forward, I must disclose that I am not Native Hawaiian. I am a fourth-generation local, born and raised on Kauaʻi, with ancestors who emigrated from Japan and Portugal to work on Hawaiian plantations. I grew up respectfully rooted in a place in need of amplification of Indigenous voices and wisdom. A place with words and ideas and meanings and actions that remedy the ills beyond our bodies—knowledge we call upon to operationalize care.

A global disease presently calls us to both do carework and be careworker, intensifying our current roles or necessitating others. But the act of helping on a large scale—typically in response to caring—requires mutuality, and not everyone is answering the call. Am I?

Privilege in Pandemic: A Reckoning

The decision to proceed with this submission was difficult for me. I recognize and support that the purpose of this issue is to feature scholars most affected and burdened by COVID-19 and the resulting intensity of carework. My aim here is not to hitch my story to those needing to be told. Rather, as a first-generation and first-year PhD student in technical communication and rhetoric, I hope to highlight the disproportionate levels of pandemic-induced pressure, anxiety, and pain accompanying marginalized scholars in our field. I want you—academics, practitioners, students, readers—to know that you are seen, heard, and cared about. In this personal narrative, my hope is that others might realize more (multimodal) opportunities of performativity during the pandemic.

-----

From onset to present-day pandemic, I do not have children. I do not have parents who require my constant care. My spouse and I, while in some ways considered “at-risk,” do not have chronic illnesses, injuries, or disabilities. We both have steady jobs in our respective fields. We have a home. For the first time in my multiply marginalized life, as a biracial woman from a place with deep colonial wounds, I felt situated in extreme privilege.

Me? Privilege?

Yes. In the COVID-19 era, I have little to no carework beyond that of “the before times.” While grateful for everything in my life, I have never felt so earth-shatteringly uncomfortable about my circumstances. The feeling of guilt is pervasive, but something more powerful motivates my actions: recognition of the kairotic moment for kokua—and knowing what to do about it.

Composition as/in Carework

I would be remiss not to credit my inspiration to the most exciting rhetoric book that I acquired “for fun” during the pandemic, Ann Shivers-McNair’s (2021) Beyond the Makerspace: Making and Relational Rhetorics. While I am still reading the book at the time of this writing, I appreciate the inquiries into who can be a maker and, relatedly, who can be a writer. On a good day, I count myself as both. In following these thoughts, I wonder: who can be a careworker, and what does it look like for me? Do I need a direct recipient of care?

Scholars of care and carework, particularly in connection with technical communication and rhetoric, have researched and answered such questions, but for me, this is all new ground. In fact, it was not until the call for papers for this special issue, coinciding with when I began Shivers-McNair’s book, that I started piecing together how an urgency to do carework in my own way sparked multimodal composition from myself and others.

I focus my care efforts on careworkers, and by extension, those in their care.

This is a story of how making created a ripple effect of composition as care and composer as careworker. It is a story of multimodality, mutualism, and purpose in a pandemic.

-----

My maker identity is primarily as a papercrafter, though I work with more than just paper materials. As an avid cardmaker (i.e., greeting cards), I felt compelled to use my craft to facilitate connection during COVID-19. Postal mail, after all, can traverse pandemic boundaries. People sought a return to tangible, material communication, a good old-fashioned card against unwanted bills and junk mail—especially with the sudden physical isolation of social distancing.

Taking to social media, I created a photo gallery with dozens of card designs and descriptions, offering for my Facebook connections to choose what they wanted for free. I covered the shipping, even to those located in my community, to encourage contactless exchange and eliminate worry for immunocompromised friends. The intent was for people to use the cards to write to those they could not physically visit. In many cases, either the sender or recipient of the card had difficulty using technology (e.g., Zoom, Facetime, email, etc.) to communicate.

This project became my purpose as a collaborative careworker, supporting those who were caring for others in their lives. While the card gallery was taken down after all the cards were claimed, I documented these efforts on my public Instagram page (Figures 1 and 2). The responses to this project surprised me, as so many people—unprompted—chose to contact me publicly and privately via social media and text to share who would be receiving the card and the circumstances surrounding their need for connection. I sent cards to people, who sent them to other people, all over the country: grand/children away at college, grand/parents in care facilities, injured or ill relatives across the country, or friends seeking to reconnect.

Interestingly, some felt their request for more than one card was selfish or asking too much. Others insisted on paying. I encouraged them to take what they needed and to accept them as gifts. And together, mutually and wanting nothing in return, we reached who they cared for in a meaningful and accessible way.

After writing in their cards, some people wrote me thank you messages, whether digital or handwritten and mailed back to me. Some of the recipients of cards wrote to me as well, describing how the card from their loved one lifted their spirits. I am grateful to be able to use what I have in materials or skills to meet a need—to do what is in my nature at a time when kindness and care are critical.

-----

Simultaneously with offering free cards, I set a personal goal to mail a handmade card to at least one person in every U.S. state during 2020, a project I learned from my fellow cardmaker and friend (@snippetsbyandrea) on Instagram. While I wrote in most cards, I tried using plain-text QR codes in a small handful. This approach allowed me to write more than I typically would be able to fit in a standard A2 greeting card and introduced an interactive digital element for the recipient to read the message (accessible with a smartphone camera). I printed and adhered the code into the card with brief hand-written instructions about how to read the message. The non-digital card purist in me is still cringing at the inclusion of a digital element, but people seemed to enjoy a different take on snail mail writing.

Once again, several people wrote back to me and expressed excitement at being included in the goal. One person, also a cardmaker, decided to take on the goal as well, striving to mail to all 50 states that year. More making, more composing, more carework. More ripples.

All told, between cards given away and those sent for my personal goal, I mailed 275 handmade cards in 2020. The number increases if I include those sent during 2021-2022, but I have stopped counting. When our lives shifted to digital formats, this return to the non-digital pushed back on pandemic norms. It was, in a way, my own personal COVID-19 communication rebellion.

Making and Being Remade

My writerly life during COVID-19 also involved multimodal composition, segmented into projects focused on my own self-care, care for others, and academic pursuits. For documentation’s sake, following is a list of pandemic-era writing and editing:

Composition Carework for Self [See Appendix]

- Journal writing. During the 2020 holiday season, I treated myself to a lined journal that was handmade from one of my favorite children’s books. Beginning in March 2021, in atrocious handwriting, I added entries mainly to try and process my COVID-19 feelings and experiences.

- Social media writing. In response to acts of Asian hate nationwide, sparked by COVID-19, I wrote Facebook posts about my experiences as a half-Asian woman in a conservative place. These posts generated public and private responses from friends and family who said they were struggling to put their complex feelings into words. I then hand-wrote entries into my journal.

Composition Carework for Others

- Card making and writing. In addition to the card project detailed above, I sent card kits to friends whose children needed art activities for home-school curriculums or as screenless alternatives for recreation. These kits included prepared components of cards that the children could assemble, further customize, and write in before mailing.

- Instructional writing. In January 2021, my supervisor, the editor-in-chief of a science journal, contracted COVID-19 and was out for approximately six months. During his recovery with long COVID-19, I wrote instructions and boilerplate communications for the interim editor. Texting became a new, frequent, and effective form of correspondence.

- Article editing. I edited a friend’s research article revision. (It got published!)

- Application material editing. I edited a friend’s cover letter and resume for job applications. (She got a new job!)

Receiving Writerly Carework

- Personal statement. In the summer of 2020, I decided to pursue a PhD. Throughout the fall, I wrote the personal statement for my program application, considering for the first time what my area(s) of technical communication and rhetoric research might be. This involved consulting with a faculty member at the institution I now attend, who graciously extended writerly carework toward me in providing feedback.

- Abstract submission. Days before writing this submission to the Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, I finalized and submitted my first conference paper abstract. Again, I consulted with a (different) faculty member at my new institution, who provided feedback as writerly carework during summer 2021, while I was not yet officially starting my PhD program until the fall.

Conclusion

There is a television show called Making It, which is the only program I prioritize watching weekly as it airs. The on-set makerspace, a fresh and vibrantly colored barn, complete with a barn quilt and seemingly endless supplies and inspiration, is straight out of my dreams. Making is central not only in caring for myself but in strengthening relationships and creating meaningful communication toward others, no matter the state of global health. Making is, paradoxically, at least in my case, both invigorating and exhausting. In pandemic life, I am drained but hopefully still composed and composing. I balance making as my own kind of carework while deadlines loom in every direction.

The takeaway from my experience is that carework, or the embodiment of kokua, is for us all. It is not reserved for those inheriting a culture and not just enacted during a crisis. It is also not about the artifact made but about the meaning, thought, care, and process inherent in what is made. There are many approaches for what carework is and looks like based on who is doing/being and who is receiving. In the blur of COVID-19, I maintain that a lens of kokua renegotiates carework boundaries, overlaps roles of careworker and cared for, and reframes what constitutes care. These lines and roles must remain fluid to meet needs mutually and sustainably.

Whether our carework is direct or indirect, it is our response to the call to do and be that matters. In the time of COVID-19 and beyond, we will find ourselves continually, inextricably, at the intersection of caring about writerly needs and serving those who need us to reify care. Exhausted as we are, have been, and inevitably will be, the exigence persists—and so do we.

Works Cited

Shivers-McNair, A. (2021). Beyond the makerspace: Making and relational rhetorics. University of Michigan Press.

______________________________________________

Appendix

Images

Figure 1. Instagram post, March 23, 2020: “My first official @mailitmonday is a big one!! I had a bunch of cards made and packaged up before the #covid_19 threat, so I offered to send them to my friends on Facebook so they could send them to family and friends they can't visit right now due to #socialdistancing ❤ I had so much fun posting pics of cards, letting people choose what they needed, and hearing about the special people in their lives that these will go to. Each card and envelope was already in a plastic sleeve, and I put the whole thing in an outer envelope. I'm so happy to get these in the mail 💌”

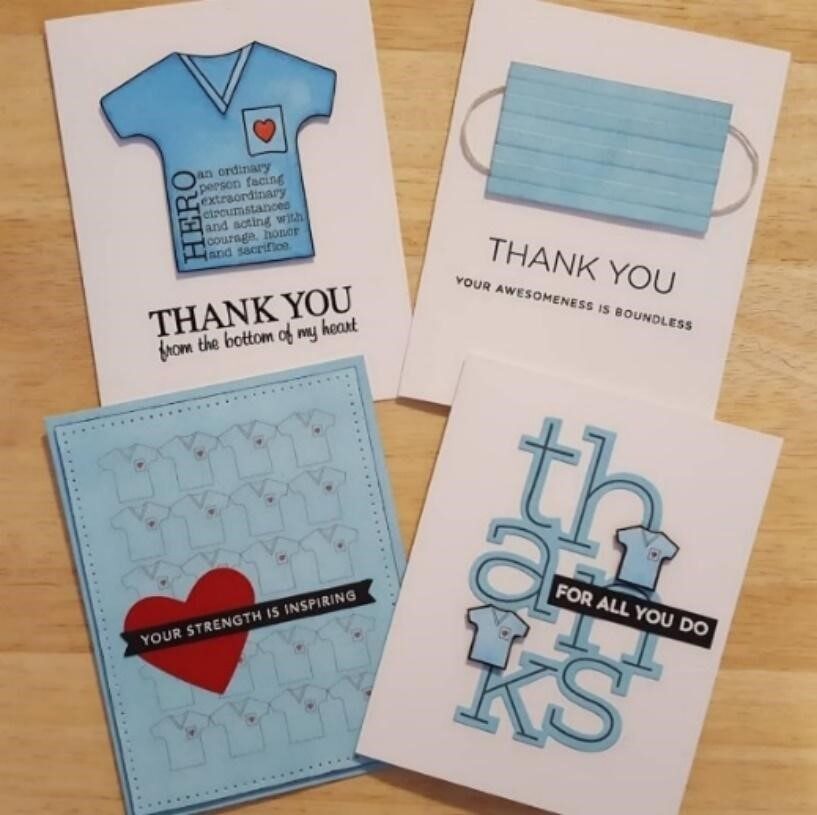

Figure 2. Instagram post, May 3, 2020: “I made a bunch of cards to thank and support healthcare workers. This was my first time using digital images on my cards, thanks to the opportunity to download the scrubs image for free from @ajillianvancedesign (THANK YOU!) ❤”

Audio Files and Transcriptions

March 8, 2021

Today is International Women’s Day 2021. What better day to begin this journal, made into a notebook from the pages of my favorite Little Golden Book. It’s been a long year of COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing, political turmoil—such that I felt the need to write down my thoughts and emotions, even though I am really not one for journaling.

VACCINATION

Three days ago, on March 5, I received my first COVID-19 vaccination shot from the pharmacy of our local grocery store. It followed several days of intense emotional guilt for me, as I did not believe that I should receive this vaccination ahead of so many others whose risks and needs were far exceeding my own. . . I qualify because I am a professional staff person for [a university] even though I work remotely. . . I therefore have no face-to-face exposure or requirements in my job, and it is not a teaching position. I was ready to step back from any further attempts to secure a vaccine appointment when more spots came open through [the grocery store] and I got an appointment. This was much more important to my spouse than it was to me. He was, at the time, already fully vaccinated (2 shots) because of his status as high-risk. His job. . . began requiring more face-to-face interactions, and he was afraid of bringing the virus home to me. Although relieved to a certain extent, I cannot fully shake the feeling of guilt that many people, including my mom and step-dad in [another state], both high risk but under 65 years old, have not yet been able to get their first vaccination shot, despite being very anxious and desperate to do so.

-----

I will never regret voting for [people] who support science, truth, and social justice. It is largely because of my belief in such things that I felt my guilt. I am situated in a position of privilege, and it bothered me. In addition to being less exposed and with no health concerns, I am fine to remain socially distanced for a while longer, whereas many people have had more difficulty in isolation in the past entire year. I did not post about my first shot on social media because it did not feel right to do so, with so many others still waiting. I felt ashamed, like I needed to conceal this fact about myself, instead of feeling happy, proud, and relieved to be safer. It was also important to my spouse that my vaccination be a positive experience, but these feelings are still with me. I grew up learning. . . that one should never put oneself first or take something that anyone else wanted or needed. I practiced this in my daily life with all things, never putting myself first or taking, but actively putting myself last and giving. A short while ago, my dear friend. . . posted a video about not only giving but also taking care to receive blessings. It hit home for me. I am still having a hard time accepting what has been a gift and a blessing, but I realize the importance now of doing so.

March 18, 2021

#STOPASIANHATE

The following entry was typed and posted to Facebook on 3/18/21. It received 130+ interactions/responses and 9 shares, to date. Several people contacted me privately to say that I had expressed words that they were not yet able to formulate about their own feelings surrounding attacks on Asian people because of negative perceptions from COVID-19.

___

When I first moved [here], someone who assumed I was white and found out I was half Asian said: “well, to me, you look normal, but you never know”—suggesting that non-white people look abnormal, and that at the same time, I was somehow deficient in being recognizable as what I am. This is not an example of race-based physical violence, but this is the seed from which it grows. This is racism at the day-to-day level, the “happened to someone I actually know” level, committed by people who are not challenged to shift their views or behavior by those with the power to influence them.

My family is legitimately worried about my safety out here because of the recent upsurge in violence against Asian people in America. They say it does not matter that I am and have always been an American citizen and that I live in a mostly “safe” place with mostly “nice” people—that there is still the potential for someone to take one look at me, make one assumption, and do something hateful and irreversible. I am still merely existing as Asian in a place that is mostly white and extremely conservative. Admittedly, in racially charged situations, my instinct is to lay low. This is safer, but it is wrong. I am half Asian. I do not wish to sit down and hide while many of my friends and family are feeling even more exposed and afraid.

Yesterday, as I was heading out to run a necessary errand by myself, I had a sudden wave of fear. I rationalized that everything would probably be fine because of the place I was going, how quick I’d be, lots of people around, and my mask making it harder to distinguish some facial features anyway. Keyword: *probably*. To be honest, I still felt scared. I still felt like hiding. Have you ever felt targeted? It sucks. And my experience is mild compared to so many others.

I started writing in a journal, which has helped me process some emotions that I don’t like dealing with. This is an entry that I decided to type up and share, which I will paste into my journal for today. It is a raw and vulnerable account of what your typically quiet, composed friend is struggling with during this busy workday. If you’ve experienced similar feelings, please know you are not alone. If you do not understand why this matters, I hope your heart will change.

Bio

Rosanna M. Vail is a PhD student in Technical Communication and Rhetoric at Texas Tech University with research interests in the rhetorics of science, health and medicine, accessibility, and social justice. She works as the managing editor of a peer-reviewed open-access science journal and as the technical editor of various scientific monographs. An avid papercrafter and postage stamp enthusiast, she uses creative processes to support organizations and causes in her community.